It is disconcerting, I have to tell you, to load a friend's blog over your morning coffee and be greeted by a post that opens thusly:

I was, actually, aware that cannibalism was an option in the new Oregon Trail Facebook application; as I explained to my bewildered friend in comments, if you are eaten on someone else's wagon train, it shows up in your newsfeed—which is how I found out a couple of weeks ago that I had been devoured by another member of my department. This was a cause of some concern for the author of the post, who mused that perhaps he shouldn't just agree to every Oregon Trail invite he gets if people are only inviting him for the protein: "It costs nothing to invite a friend on your wagon, but it's $85 for one box of food. You do the math."

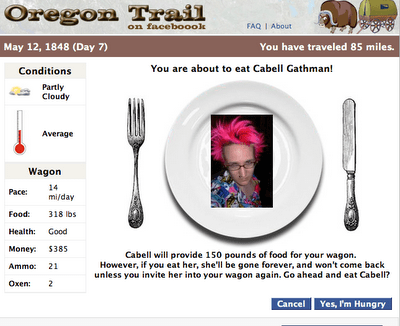

In fact, you even get money for inviting a friend to your wagon, which is obviously intended to encourage you to invite as many people as possible, spreading word of the application. At any rate, while I had discovered that it was possible to be eaten, I didn't realize that it involved such a high degree of intentionality. My friend generated the above screen by innocently (he claims) clicking on my name in his wagon train roster. [1] At that point, however, he hit "cancel" and forebore to eat me. That guy from my department, on the other hand, apparently forged right ahead and sank to inhuman depths of cannibalism. I chastised him publicly on his wall, but I would have devoted more energy to it if I'd known that he ate me TOTALLY ON PURPOSE.

(I would also like to note here, as I commented on the blog post, that a) there is NO WAY that I would provide 150 pounds of food for anyone's wagon, even if you ground up all the unappetizing bits into sausage and b) it isn't even internally consistent, as the game typically awards between 80 and 120 pounds of food when you shoot a BUFFALO. People are smaller than buffalo.)

I do have to admit, while cannibalism is a new feature, watching terrible things happen to members of your wagon train was always the main appeal of Oregon Trail. For damn sure I, and everyone else I knew who played it back in elementary school, named wagon train members after friends and loved ones, and then waited eagerly for them to come down with dysentery and be bitten by snakes. The addition of voluntary cannibalism would have caused us to shriek with joy. [2]

In one respect, then, Oregon Trail on Facebook is a perfect example of the kind of nostalgic remake games I discussed in a previous column—lower tech even than the point-n-click Sierra adventures, but appealing to the same sense of childish glee. The game doesn't have to be technologically advanced to be fun. Like most of the better remakes, it also improves on some of the original offerings of the game: although the first incarnation of the Facebook app had pathetically easy and rather repetitive hunting, they improved that minigame-within-a-minigame (because what is Facebook's Oregon Trail if not a within-site offering for people who showed up to do something else?) and also added a minigame for caulking the wagon and crossing the river, which was previously left entirely to chance:

(Initially, it cost $100 to pay to cross, but apparently that was too easy.)

(You move the mouse around to steer the wagon. I suck at it—the rock-to-water ratio is often much higher.)

This is hardly the only minigame on Facebook; since applications were introduced, a wide variety have become available. Another favorite of mine is Scrabulous, asynchronous Scrabble for up to four players on Facebook. [3] Scrabulous has a non-Facebook site that is supposed to allow turns-by-email, but my experience has been that the website does not reliably communicate when it's my turn. Facebook doesn't either, really, but since I spend an undisclosed-but-ridiculous amount of time on Facebook anyway, it is virtually inevitable that I will click on Scrabulous sooner or later and see which of my games need my play. Recently, actually, interviewing someone about Facebook for my dissertation, [4] I was told that he had removed the Scrabulous application because he liked it too much—or, at least, he was spending too much time using it, causing him to feel like he was wasting his life on Facebook. I'm not sure if one should blame the Scrabulous for the Facebook use or the Facebook use for the Scrabulous, but no doubt this is EXACTLY what Facebook wanted when they allowed the integration of third-party applications in the first place: they can still exercise some aesthetic control, but users can themselves select and install bits and pieces that are likely to keep them on Facebook for ever more of their virtual activity, looking at Facebook's advertising.

Interestingly, the most common complaint I hear about applications is that they contribute to the "MySpace-ification" of Facebook. In general, what people seem to mean by this is that too many applications create a cluttered profile, aesthetically displeasing and suggestive of a user with too much time on his/her hands. (There may be an unconscious association of the increased advertising on Facebook with the applications as well, although the ads probably would have showed up with the opening of Facebook to the public regardless.) If one compares the actual functionality of Facebook applications to MySpace, however, there are only a couple of applications that actually seem to work in similar ways. "Top friend" displays that can be customized to show a user's favorite friends on the profile, and applications that allow profile viewers to play songs or clips from songs, mimic actual features of MySpace profiles, although I have yet to see a Facebook app that will play music automatically when the profile loads, the way a user's MySpace profile song does by default.

Even with the new applications, however, as I mentioned, Facebook continues to exert much more aesthetic control over user profiles than MySpace does. It is possible, on MySpace, to add third-party apps in a sense—it was always possible to add them to one's MySpace profile simply by editing them into the HTML, so that, for instance, I have a badge on my MySpace that displays my last 10 songs played as captured by AudioScrobbler. Facebook applications take it further, however, integrating applications with the site itself so that they can reach into one's actual profile and network (if given permission when added) and use the information there for its own purposes—such as providing a ready-made list of people to invite to one's wagon train:

(Whether they agree or not, actually, they show up on your wagon train—and you get $100 starting cash per invite, plus a $300 bonus for inviting the maximum 20 people that Facebook permits application invites to be sent to at one time.)

Because of this, the Facebook app also captures perhaps more perfectly than the point-n-click adventure remakes can, what was fun about the original game—in addition to making it to Oregon and living, one had the potential hilarity of one's annoying little sister getting dysentery and then falling off the caulked wagon. Now, not only does your sister get dysentery, but the game has her picture right next to the notification! And not only does the game have her picture, but if you click on that dinner plate, you can eat her! And not only can you eat her, if you DO eat her, she'll get a newsfeed update telling her that you did!

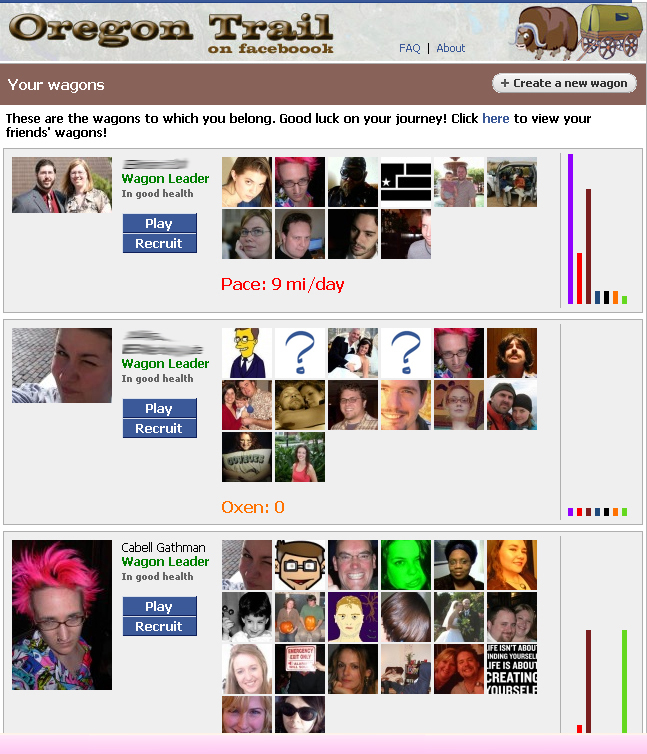

And then, of course, she might decide to retaliate by eating YOU, which is great from the point-of-view of the app designers, since in order to eat you, she needs to start her own wagon. As noted, you will show up in another person's wagon train just for being invited, whether you accept the invitation or not; your ability to participate in that other wagon is limited, but not non-existent: you can "raise money" by sending out yet more invites to friends to use the app, or you can hunt for the other person's wagon. Certainly there's been an Oregon Trail saturation in my friends network over the past few weeks; I no longer remember who invited me, but I have seven different wagons of my own (different rosters) and I'm a passenger on 11 more:

The colored bars on the right represent various wagon statistics, such as health, pace, food, distance traveled, etc. This means that you can look for someone whose wagon train has no food and shoot some for them, although having no food may also be a sign that they aren't really playing.

You want them to play, because of course that's part of the appeal—not just that you get to eat your friends, or watch them get measles, but that there's a scoreboard and you can see how you compare, to both your immediate friends and the larger world of Facebook:

It's a high-score board where the arcade is in everyone's house.

There's advertising, of course. It's not entirely clear if it's through Facebook or the application itself, but there are always ads on the game pages. It's not particularly obtrusive, except when one accidently clicks on the "continue" button for some ridiculous "crush" app instead of the "continue" button for moving along the Oregon Trail. The games are a great venue for it, keeping people ever more involved in Facebook, interacting in bigger or smaller ways with the same people they interact with via wall posts and events, and coincidentally exposed to advertising the whole time. This being the nature of both social networking sites and free online game sites, it doesn't really bother me, as I imagine it doesn't bother most users.

I do wonder if this might be a clue as to how one could take down the giants of social networking—start with a game and work your way backwards? But how do you get people playing when they'd rather play their games on Facebook anyway? I never visit the Scrabulous website. It's also hard to say how long a particular game will last. I've been playing Scrabulous for months, with lulls here and there, but who knows how long Oregon Trail will remain popular. It's definitely an improvement over the first Facebook game apps, simple random "vampires" or "werewolves" apps that seemed to be a kind of virtual collectible card game where you and your friends were the cards. I never really saw the appeal, so I don't have a terribly clear idea of how it all worked. There has to be some kind of upper limit on the complexity of Facebook games—or at least, they have to be modular and droppable at every turn. You can leave Oregon Trail at any screen and come back whenever you please (although figuring out the interface to do so could have been easier). Facebook games have to be casual games, just to fit their environment, and that's probably an advantage in terms of their viability as fads. As I remember the protagonist of Connie Willis's Bellwether noting, to get popular, fads need a low skill threshhold. [5] Facebook provides the network of people; the apps have to find the magic combo of addictive appeal, dropability, and low (but not non-existent) difficulty.

OF COURSE there's Tetris on Facebook.

[1] In fact, it appears that this may have been an elision on his part; closer inspection suggests that he had to click on a PLATE that appeared next to my name in the roster. But I suppose not everyone immediately assumes that this is a direct link to cannibalism.

[2] Years later, of course, we were naming Sims after despised former romantic partners and virtually reenacting the Cask of Amontillado.

[3] Why this isn't a violation of copyright/trademark/somebody's rights, I am still unsure.

[4] Yes, really. It's slightly less awesome than doing a dissertation on City of Heroes, perhaps, but with broader appeal.

[5] Excellent book. How often do you get speculative fiction starring a sociologist?