“Bespoke Nighmares” © 2021 by Nina Satie

Content warning:

The sign on the door said Dreams Not Sold Here, and I mostly stuck to it. Dreams were extensive and exhausting projects, not to mention expensive. Nightmares, on the other hand, were quick. On a good day, I could stitch up a hundred off-the-rack ones: you’re late for something important; your teeth are falling out; there’s someone looming over you. Even a tailor-made nightmare—like last week’s you’re being dragged into a grave by the girlfriend you murdered—I could whip out in an hour or so.

But dreams could take months, and you wouldn’t believe the cost.

So, I put the sign up, not that that stopped people from asking, especially the kind of people who weren’t used to hearing no.

It was exactly that kind of person who pushed into my shop on Tuesday night, ten minutes before closing.

Behind the counter, I tucked away a little sewing project and rose to my feet. I wore jeans and a neon yellow sweatshirt that made my skin look especially sallow. The lights overhead used too-bright bulbs that gave my hair an alien shine, unappealing and untouchable. I’d found it helped to be clear about what was for sale in the shop.

Even so, customers often looked at me and scoffed, “You make the nightmares?”

As if I didn’t have a perfectly nasty conscience.

This customer’s brows shot up upon seeing me. He was an older man, white, with light hair and teeth that looked yellow despite, I assume, lifelong dental care purchased with the same money that had bought the man’s charcoal, three-piece suit and the cream Rolls-Royce idling at the curb.

His gaze lingered on me a moment longer than I liked before he glanced around the shop’s front room: black floor, black walls, and some metal shelves with ready-made nightmares on them—velvet chokers the color of dark blood, gauzy scarfs embroidered with shining thread, suit jackets lined with a glossy something that seemed a lot like silk. The man’s expression aimed for interested but came across as amused.

I knew what he wanted.

“The answer’s no,” I said.

He smiled, charming and unfazed. “I haven’t asked a question, nor introduced myself. I’m John Havingsworth.”

“The shop’s called Bespoke Nightmares. I don’t sell dreams.”

He seemed put out that I’d guessed what he wanted. His smile wavered. Then, something close to graciousness oozed over his expression. “My dear,” he said, which I was not. “I’m well aware of your talents. I’ve used your sinister services before.”

Of course he had.

“Though I didn’t come down here myself.”

Of course he hadn’t.

He strolled closer to me, as confidently and carelessly as someone who’d never wondered who the threat in the room was. “And I’m convinced you can help me. You see, I’ve sampled the finest this world has to offer—the rarest vintages, the most sumptuous silk, the grandest views to ever grace a man’s eyes. But I find I’ve become … inured to the luxuries of this world.” He reached the back counter and slanted me a conspiratorial smile. “I’m afraid I’ve begun craving wonders I’ve never dreamed of.”

I didn’t need the backstory. “No.”

The shine in his eyes brightened to become wolf-like. A man in pursuit of prey. “I’m sure we can come to an arrangement.” His gaze moved to the laundry cart against the wall, full of ordinary clothes. “You wouldn’t have to do any mundane mending to keep this place going.”

“No.”

He leaned his hip against the counter and sighed. “That is disappointing. It would be such a shame if you had to close.”

And, the heavy silence told me, he had the power to cause such a thing to come to pass. I rested my fingers on the worn handle of the pickaxe I kept beneath the counter. My mom had gotten out of the business because of people like John Havingsworth.

“I can’t pay the rent with threats,” I said. “I can’t eat them, either.”

He chuckled like we were sharing a joke. “Surely not. I’d make it worth your while.” A pause. “Unless you don’t think you could make it worth mine. You are an expert in nightmares, after all. Not dreams.”

He was needling me, and it was working.

It wasn’t like I couldn’t use the commission. In the back room, some of my supplies had dwindled to nearly nothing. I had enough rolls of silky white terror and plenty of prickly bolts of unease on the shelves. But I’d begun rationing my last ream of guilt, seductive as velvet. And my stock of already-spun desperation, sheer and fluttery, was all but gone. Even my store of raw desperation, from which I spun the thread, had nearly dried up. Only a few tendrils dangled out of the cabinet where I kept the unprocessed material.

None of those supplies were cheap. That’s not why it was less expensive to make nightmares than dreams. The cost effectiveness came courtesy of the human brain, which was evolutionarily wired to believe bad things more easily than good ones. It took only a stripe of unease or a few stitches of dread to leave you shaking and nauseated after a nightmare. It took pounds of material to stitch even a barely memorable dream.

I considered Havingsworth. He sensed my pending agreement, and the way his smile deepened almost made me change my mind.

Instead, I told him he’d have to pay for my time and materials. Plus a fee for the dream creation itself. The figure I named made his mouth go flat, which meant I’d gotten it right. And I mentioned that dreams didn’t always turn out as expected.

Havingsworth brushed it off, paid an advance, and left my shop humming.

Please note that I did warn him.

It wasn’t hard to design a dream for Havingsworth. He’d laid out what he wanted: wonders beyond this world. Since he was of European descent and possessed little imagination for himself (an expensive suit and a Rolls were not the accessories of a creative mind), I went for the classics.

That night, I left jars on the roof of my building. Two big ones had some milk in them to capture moonlight, and the smaller vials were made of such fine, clear glass that starlight couldn’t resist filling them up. In my kitchen, I made a loaf of crusty bread and siphoned off its heat as it cooled. I woke at dawn to collect pale gold sunrays in a silver hand mirror. On the way to work, I found a leaf a butterfly had slept on and brushed its iridescent wing dust into a plastic baggie.

I spent a week gathering materials—the velvet feel of cool grass, women’s laughter bouncing off chandeliers. I even lured some shadows into an empty wine bottle. A few winter-dark shadows in a dream made everything else seem all the brighter. By the time I had enough to get started, my squinting eyes ached, and I’d collected a tapestry of bruises from crawling around.

In between my regular nightmare stitching, I spun my light and shadows and gold and glitter into the threads and fabrics I’d use for Havingsworth’s dream. It was not easy going. The spinning wheel in the back room clicked and clacked, throwing off sparks that singed my hands and lit my hair aflame. The dawn rays got snarled. The shadows unraveled nine times out of ten. My hands went numb from the moonlight. But slowly, my pile of supplies grew taller, shinier, more irresistible.

A month later, I knew I’d have to gather more materials—starlight evaporates damn fast—but I had enough to begin stitching. For nightmares, I often started with a base garment of regular fabric. Human brains supplied mundane details on their own. All I had to add was the horror or the dread that turned the world inside out. For dreams, I had to make it all from scratch.

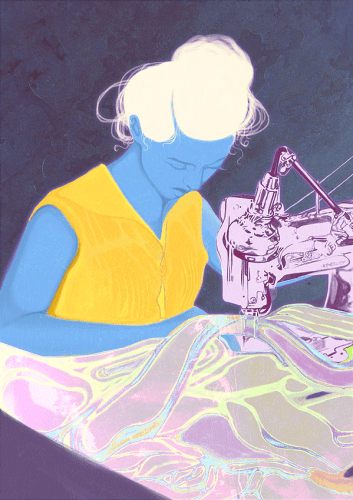

My antique sewing machine sang as its needle plunged through the fine fabrics. I used the machine to stitch together the base of the dream. But for the fine details—the gold embroidery, the crystal embellishments—I used my hands and a bone needle even older than my sewing machine. I didn’t enjoy hand-stitching. My fingers cramped, and I always ended up hunching my back. Plus, it was best to stitch dreams by candlelight, so my eyes were burned red and dry by the time I finished Havingsworth’s dream, two months later.

He came himself to pick it up. I watched him marvel at the long blue coat, stiff with embroidery and glittering details. The coat would lure his sleeping mind to a midnight ball in a wood that dripped with jewel-like fruits. Musicians would play harps strung with moonlight. Cups would overflow with star-silver wine. Guests would speak with velvet tongues and kiss with silken lips.

Havingsworth seemed half in a dream already as I read the instructions to him:

Wear the coat to bed or for a full seven hours before so the dream would have time to sink into his mind. The dream would start whenever he first fell asleep. Even a ten-minute power nap would trigger it. After the dream ended, the coat would dissolve. He shouldn’t let anyone else wear it.

Havingsworth nodded, praised my work, paid me, and waltzed out the door with the coat in his arms like a corpse.

The first dream satisfied Havingsworth longer than I’d thought. He didn’t swan back into my shop until three months had gone by.

He wanted another dream.

I refused. It took too long, it made me ache, and it would be harder to enchant him a second time.

His charm faded faster than it had our first meeting. I rested both hands on my pickaxe as he threatened me.

“Fine,” I said eventually. “But it’ll take longer and cost more.”

He smiled, all yellow teeth, shiny with saliva. “Name your price.”

I did. He didn’t balk this time. I sent him away and started work on the second dream.

It is harder to please a mind a second time. But I was far from unable. For this dream, I gathered the warmth of the inside of a fur coat, the cool kiss of pure silver, the softness of swans’ feathers, and even more starlight.

The excessive amount of starlight ended up burning my retinas, a swan assaulted me in the park, and my body became a wreck from all the sewing, but even I thought the result was worth it.

I’d stitched a sweeping mist-silver cape trimmed in confidence, which I’d dyed to look like white fur. Silver thread glistened so bright that my abused eyes watered just looking at it, and the thing weighed thirty pounds from all the crystal-sharp embellishments. It had taken six months, but Havingsworth would dream of a silver castle presiding over a land of snow and clouds. He would welcome clear ice carriages and the living constellations they bore. They’d dance under a glass ceiling and delight in the warmth from their mountain-shaped hearths. He would feel like a king.

Havingsworth said it was to die for. I said all he had to do was pay. He laughed himself out of my shop.

When he returned the third time, just a few weeks later, I wasn’t alone.

A kid from the neighborhood, Farah, was digging through the laundry cart for a shirt that belonged to her sister. “Are you sure you fixed it up?”

“Yes, I used the thread you brought.”

I went to help her look, right as Havingsworth pulled up. He’d taken a taxi here, his Rolls-Royce nowhere in sight. His suit was missing two pieces and its tie. But the biggest change was in his expression. The charm had slid off entirely, leaving nothing but a baring of those yellow teeth and a familiar hunger in his roving eyes.

“I’ll bring it to you later,” I told Farah.

“But it’s twenty blocks—”

She fell silent as Havingsworth prowled into the shop. “Evening,” he purred. His eyes darted from me to Farah. “Here for a dream as well?”

“She’s leaving,” I said and escorted her out.

“I’ll take another one,” he said before the door had fully shut.

I walked to the back counter. The too-bright lights cut my cheekbones into knives. “No. You can’t afford it.”

I knew the signs. Car gone. Clothes rumpled. He’d spent all his money chasing how he’d felt in the dreams. Probably made some bad business decisions too.

Now he showed me all his teeth. “You don’t tell me what I can and can’t afford.”

“I just did. And I don’t work for free. Get out.”

The hunger sharpened in his eyes. “You can’t afford to turn me down.”

When I refused again, he tried more threats. Then he cajoled. He’d introduce me to his friends. I’d make millions. Finally, he resorted to pleading. When I told him to get out a second time, he did.

I expected to see him again, but I misjudged the timing. I’d thought it’d be a week before he crawled back into my shop. Instead, it was three days. And I wasn’t behind the counter in the shop. I was on the sidewalk after sunset, and he appeared from the shadows of the subway entrance.

The gleam in his eyes was unmistakable: he was here for me. I broke into a run. He did too, chasing me down the empty sidewalks. His feet slapped against the pavement, and his harsh breathing reached my ears. I could almost feel his reaching fingers. They would sink into me like claws, disemboweling me for a dream.

I got my keys out as I ran, but it still took precious moments for me to unlock the shop. Havingsworth was so close that I clipped his head with the door as I whipped inside. He followed, lunging for my waist. His fingertips grazed my jeans.

I vaulted over the back counter, grabbed my pickaxe, and swung.

The point pierced Havingsworth’s chest dead center. The impact reverberated up my arms. For a moment, excluding the pickaxe, it felt like the first time Havingsworth had come into my shop, leaned against the counter, and asked me for a dream. He tipped his head down to see the wound. One shaking finger touched the liquid dripping from it. His brows popped up in surprise. Then the present came rushing back, and Havingsworth collapsed backward. The pickaxe released with a wet shuck.

I let out a breath and dropped the axe head to the floor. My grandmother had preferred a longsword, and I got that it was easier to swing and had more edges for slicing. But I liked the deep, central hole the pickaxe left. It was like a well.

“I warned you,” I told Havingsworth, who wasn’t quite dead. He couldn’t move or make a sound, but I always thought they could still hear. “Dreams don’t turn out like you think.”

I dragged Havingsworth’s body into the back room and opened the cabinet where I kept my raw supply of desperation. The black material that fed through the hole in the cabinet door matched the black liquid leaking from Havingsworth’s chest. No blood left in him; it was all desperation.

Which was a relief, since I’d completely run out. I used it in nearly every nightmare.

I finished securing Havingsworth in the body-shaped cabinet and shut the door. Just then, the shop’s front door swung open. Some kids called my name. I patted my row of cabinets. “Sleep well, dreamers.”

The kids were already in the laundry cart when I came out. I helped them find the shirts they’d left for me. Each of them now had a few extra stitches in them. They darkled like the edges of space, glinted like underwater palaces. They were little things, hints of wonder, just enough to keep them going. The kids wouldn’t end up in any of my cabinets.

After the cart had been emptied of shirts, I pulled the shades over the windows and turned the sign to Closed. Seven kids still lingered in the shop, showing each other the materials they’d gathered.

“Let’s get started,” I said. “Dreams don’t make themselves.”

And it really is too expensive to buy them, especially from a nightmare like me.