Content warning:

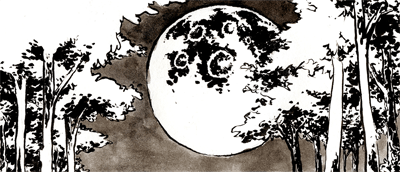

The birds are fighting again in the yard. Close to the sandbox where Kristian and Maarit are digging holes, hooded crows swoop and bat their wings at each other. From my vantage point up on the third floor, I watch their movements with unfocused eyes. Crows, their granite grey and black wings beating victory into the air, the flash of an unknown face like a fir tree–

My stomach clenches with nerves. I don’t know why. I scratch myself, can’t help it even though I promised Maarit I wouldn’t start again. Red marks run down my arms now. The kitchen of our east-Helsinki apartment is flooded with sunlight that makes the ragged lines glow.

It’s the dream. It faded to a wisp the moment I struggled to consciousness, but its ghost lingers at the back of my mind like a stormcloud on the horizon.

My coffee cup is slick with sweat against my hand. I down the rest of the mellowed-with-milk brew without ceremony and fold the newspaper back up without reading it.

There’s packing to do, holiday reading to select. We’re due to leave in three hours. No time to catch the memory of a dream. No time for ferreting through the tangled mess that’s my head. I’m done with all that.

Cloudless sky, the sun blinding the world. I’m glad when I turn from the motorway to a gravel track leading deep into the woods, where the leaves offer occasional shelter from the relentless light.

Kristian is fidgeting and asks the dreaded and inevitable question for the umpteenth time. "Mummy, Ma, are we there yet?"

"Almost there, sweetpea," says Maarit, sharing a grimace with me. I’m concentrating on remembering precisely which wooded path it is that leads to my family’s summer cabin. Sometimes it feels like the forest changes. . . .

I’m slick with sweat and Maarit’s open-necked blouse is stained below her breasts. Damn this heat wave. No wonder Kristian is so desperate to be there already: our air conditioning sent in its resignation letter a bare fifty minutes into our three-hour drive.

"Let’s play a game!" Maarit improvises, squirming around to face Kristian, who’s secured in his chair in the back seat. "Let’s count all the birds we see! Look, that one’s a crow."

The game keeps Kristian content for a while. Exhausted by the birdwatching and the heat, he eventually snuffles to sleep. I sigh in relief and smile at my wife.

Maarit touches my cheek. "Storm’s building up."

I glance at the sky. Dark clouds are gathering on the horizon. "I hope we get to Kallavesi before it breaks."

The final stretch of road barely deserves the name. It’s just enough of a dirt track to let a car inch along through the forest. The cabin’s outhouses begin to be visible through the trees. Relieved, I pull up beside the woodshed, next to my father’s and Aunt Pirjo’s cars. After the engine’s rumbling stills, the world is filled with quiet. We bundle out of the car as quickly as possible. Kristian grumbles a protest at being shaken awake, but he perks up when he realises we’re here. The air outside is hot too, but at least there’s a breath of wind from the lake.

I still feel heavy and muzzy-headed from my forgotten dream. I close my eyes for a moment and listen to the wind sighing through the birch-leaves and fir-needles. Somewhere, magpies chatter and a blackbird warbles. Summer sounds, cabin sounds.

"Elna! Maarit! Let me help with your things."

It’s Pirjo, a brisk, bustling presence in her bare feet and stretched-out summer dress. Kristian runs over to her with a squeal of delight and she ruffles his dark hair. "Your grandmother came along after all," she says to me, "so you lot will be sleeping in the sauna dressing room."

"Suits us," says Maarit. She rummages in the boot of the car, heaving out our bags and Kristian’s collapsible cot.

I help carry our belongings to the sauna at the lakeside. After we’re settled, I take off my sandals and let my feet protest at the rough ground beneath them. Not as hardy as they used to get during time-suspended childhood summers spent here. In a bare week, they won’t have time to get calloused. But it’s a tradition, a ritual, to take off my shoes here.

We all troop to the cabin itself. The sight of the simple log house brings me back to my childhood, as it does every time. The wind chimes greet us with a gentle tinkling as we climb the steps onto the veranda.

Inside the thick log walls it’s cooler than outside, a blessed respite from the heat’s beating. The cabin smells of homely, welcoming things: coffee, old timber, a hint of lavender. Paradoxically, the ticking of the cuckoo clock by the mantelpiece makes time seem to stand still. The floor is covered in rag carpets made by my grandmother Kristiina.

And there she is, in the rocking chair by the fireplace.

"Granny," I say gently, going over to hug her.

Kristiina’s face spreads into a many-wrinkled smile. "Elna! And is that little Kristian?"

Kristian, always a little wary of his great-grandmother perhaps because of her advanced age, goes dutifully to get a hug.

Maarit greets Kristiina with a warm handshake. My heart fills with gladness whenever I see my grandmother’s face light up as she sees my wife. Kristiina welcomed Maarit from the moment I first introduced her as my girlfriend. Years later, I still remember the weight of fear shifting off my chest. We named Kristian after her; it was Maarit’s idea.

Perhaps all summer cabins feel like this: like every childhood summer distilled into a pure, potent presence. I feel safe here. When I was a child, our summer cabin was a refuge, a place where I could be myself. When I was a child. . . .

A nagging taste-memory I can’t place, honey on my lips, buzzes in my head like a wasp and makes me irritable.

I’m glad when my father enters the cabin and fills it with his deep-voiced, jovial presence.

We’re on the veranda drinking afternoon coffee. Pirjo has set out at least five different kinds of biscuit and cake. I drink my coffee and nibble on a sweet cinnamon bun, idly listening to the others’ talk.

You can see down to the sauna and the lake from the veranda. A winding path leads there through the underbrush and trees. The lake glimmers in the searing sun. The wind has grown in strength and is rushing through the birches by the lakeside. The storm hasn’t broken yet, but it won’t be long. Dark clouds are gathering.

"Mummy, look!"

Kristian patters to me and presents a triumphant find. It’s a small white stone, perfectly rounded. I take it in my hand and a ringing fills my ears. I shake my head to get rid of the sudden strangeness. "Where did you find this, Kristian?"

"Over there," he says with a four-year-old’s vagueness, waving his arm somewhere around the cabin grounds. "A bird gave it to me."

Maarit chuckles, a warm sound that grounds me and brings me back from the buzzing unreality I was getting caught up in. "A bird?" she says. "What kind of bird?"

Kristian screws up his face in concentration. His expression clears suddenly. "Like that!"

We all look to where he’s pointing. In the small area of cleared grass in front of the cabin, a magpie preens and chatters, dancing and spreading its blue-tinged wings, flaring its long tail-feathers for balance.

"A magpie laughing in front of a house," mutters Kristiina, "means bad things are coming. Old things."

"Old superstitions!" My father laughs. "Have some more cake, Mother."

The magpie shimmers in the sun, its feathers gleaming blue-metallic. I can’t keep my eyes off it. Only when it takes off and flies into the forest, towards the lake, do I come back to this world.

The white stone is still clutched in my hand. It should be hot and sweaty from contact with my skin, but it’s cold. As if it had that moment appeared from the bottom of a lake.

That night the storm lulls us to sleep, breaking the heat’s back, a momentary respite. Before I head to bed in the sauna’s dressing room, where the boxbed has been spread to accommodate me and Maarit, I stand outside the sauna building and let the rain bathe me. Eleven-thirty in the evening and it’s still twilight. Even the rain-clouds can’t make it dark yet. Summer sings in me. I get drenched on purpose, let the rain unleash a longing on my skin. When I get inside, Maarit enfolds me in her arms.

I awake to the sun filtering through the old lace curtains. Maarit is fast asleep, her hair spread on the pillow in a brown cloud. I smile and resist the urge to run a hand along the naked curve of her back. I don’t want to wake her.

I check my phone. Four in the morning, far too early for even Kristiina to be awake. I feel too hot and the air in the room is stifling me, so I get up and slip on my light flower-speckled sundress. It clings to my damp skin. I check on Kristian in his cot and another smile reaches the corner of my mouth. I pluck my towel from its hook, linger at the door for a moment watching my sleeping family.

Then I go out into the morning.

The sun has risen half an hour before, but the world is still dew-dripping and new. The birds are noisy in their celebration of the dawn, their chattering louder than it ever is in the city.

I can feel the heat of the day building up. I have to swim. Perhaps the lake will help me cool down a little. No one else is around yet. I can feel the sleep-energy spreading out from the cabin and sauna house . . . No, of course I can’t. It’s my barely-awake brain playing tricks on me.

The floating jetty creaks and rocks beneath my bare feet. The branches of the silver birch beside it tickle my neck as I pass. It feels as if spirits are stroking my skin, and I shiver.

I strip my sundress off and let the burgeoning day’s heat lick my body. I feel a tingling all over, an itching I’m not sure is merely physical. The lake is calling to me. A vast stillness has spread over the waters. I slip in.

The lake-water is warm, but still cooler than the air. It slides around me like birdmilk. With strong, steady strokes I swim out. The shore on the other side is still half shrouded in morning mist. I plunge my head underwater

–and feel I’m being sucked under, memories flood me with the raging power of water, I’m raising my hand in supplication to the great bear-queen, who tells me I am the one to help their world in its direst need –

I emerge from the lake, gasping for breath.

I remember.

That summer, they called to me through the lake and I followed, passing through the water next to the guardian birch. When I reached the surface again, spitting lake-weeds from my mouth, I was Elsewhere.

Yes. When I was eleven years old, I helped save the bear-queen’s world from the troll-king’s dark magic with my groundedness, my imagination, my human blood. They sent me back afterwards, sore and scraped to the depths of my soul. Crows sent new memories into my parents’ dreams so they wouldn’t know their daughter was gone for three days, rescuing another world from bloodshed and evil. They thought they had nursed me through a light but persistent fever during those days. Then the crows ate my own memories of the otherworld until only wisps were left.

Now, as I abandon myself to the water’s grasp, those half-forgotten wisps are twisting together. Each memory opens a new gateway in my mind till I can piece it together, till I truly remember. It’s impossible, but as I float on the lake’s sun-shimmering surface, I know it’s true.

The white stone is still in the pocket of my sundress. And now I know where it’s from. I know why it doesn’t heat up in the sunlight of this world. I shudder. Kristian said a bird gave him the stone. Yesterday I thought it a child’s fancy.

I climb up onto the jetty, drying myself and pulling my sundress on, barely noticing what I’m doing. It’s still earliest morning although I feel I’ve been in the water for many ages of the world. The cabin and sauna are soft with my family’s sleep.

A fluttering breaks through my thoughts. I glance up into the birch tree. On its branches sits a jay, the blue-black patches on its wings standing out in the morning sun. It’s staring at me.

I stare back. The bear-queen used to be surrounded by crows, magpies, ravens and jays. They sent her messages throughout the land, came back bearing truths and news.

"What do you want?" My whisper breaks the lake’s silence.

The jay’s cries sound like a pale imitation of my words at first. But soon I realise it isn’t just imitation. I can understand it.

Birds can’t speak our language. But sometimes you can understand them, nonetheless. And birds can fly between worlds.

"The queen is dying," the jay sings. "The queen is dying."

The jay’s words bring images to my mind. When I close my eyes, I see the bear-queen borne down by her long labour to make her land a better place to live. She is much aged from the last time I saw her, twenty years ago. She lies on a golden bier laden with flowers, grey speckling her pelt, her crown burnished bright. She is preparing for death.

Sorrow tears at my insides. For a brief while, I was friends with her. Now she is dying.

I feel like I have to do something, but I don’t know what. I touch the white stone in my pocket and feel it whispering to me. Go back. Say goodbye to her.

A wail rings through the air. Kristian must be having another of his nightmares. I feel tugged in two directions but my son’s fear leads my steps back to the sauna building, back to where Maarit is comforting him.

"Too hot to sleep?" she asks when I come in.

I nod, too torn apart to produce words. I step into the circle formed by my wife and child. I hold them close to dispel my own memories as much as Kristian’s nightmares.

I’m restless all day, and although I try to hide it Maarit keeps asking me if I’m OK. I try to smile, touch her cheek, but I can’t tell her anything. She’d think I’ve gone mad.

That evening we’re sitting on the cabin’s veranda. The air is like silk, finally cooling down. My father and Kristian are still in the sauna, Kristian most likely splashing around with the pails full of lake-water and having the time of his life. But Maarit, Aunt Pirjo and I are sitting there sauna-fresh with Kristiina. She doesn’t like the sauna any more–too hot for my old bones, she says.

"Can’t believe I felt like having a sauna in this heat," said Maarit. "But it was amazing." She takes a sip of her post-sauna beer.

"Hasn’t been this hot in years and years," says Aunt Pirjo. She looks at me, a strange glint in her eye. "Not since the summer Elna had that persistent fever, come to think of it. How old were you then, Elna? Ten or so?"

A cold weight sinks in my stomach. I slip my hand in my pocket. The stone is there, steady and cool despite the warm evening air. A stone from another world. "Eleven," I say, barely getting the word out.

"What fever?" asks Maarit. "You’ve never talked to me about it."

I realise that I haven’t. Strange, that. It’s not as if I’d realised the fever was a cover for something else till this very day. "Didn’t seem all that formative an experience, I suppose." I try to grin nonchalantly at Maarit.

"She burned up with fever for three days," says Kristiina. "We were all so worried, but the fever wasn’t bad enough to go to a doctor with. Still, in the heat of summer you never know what a fever might bring. We dosed her with medicine and herbs. We were all so relieved when the fever was finally gone!"

Such vivid memories the crows created for my family. No one could suspect that I spent those three days in a world of talking birds, water-nixies and a bear-queen, a world that had to be saved from darkness.

A hooded crow flaps past the veranda in the gathering evening, cawing in its rasping voice. Crows, message-bringers. It seems to glance at me as it flies by. Or is that just an illusion of the summer twilight?

"Bad luck, a crow flying past," mutters Kristiina.

It is indeed bad luck, an ill omen to remember magic and know that you can never go back. To know that someone is dying and you can’t even say goodbye.

Or can I? Bid her farewell, the stone in my pocket whispers to me. Come back.

"Elna." Maarit shifts closer to me in bed. It’s so hot in the sauna dressing room that we’re sticky-skinned despite the open window with its mosquito net.

"Hmm?" I feel exhausted, as if I’d just swum the lake’s breadth three times over. Memories can do that to you.

"Are you all right?"

"Of course I am. It’s just the heat. You know I don’t like it when it gets too hot."

She strokes my face from hairline to jaw. "You’ve been weird the past couple of days. Especially today."

I silence her with a kiss. "Darling," I say, "it’s the heat." I stroke her tousled hair till she drifts to sleep.

Then I slip out into the darkening early-July night. A blackbird trills clear notes into the air as I walk the knuckled path down to the lake.

The birch rises majestic above the water. I crouch on the wooden jetty and try to gather my thoughts into a coherent mass. I know that my memory of the past is true, even if it’s a truth that seems impossible when approached with the logic of the everyday world. My family would think me mad.

The pull of the past rakes my soul. I had magic for a while, in the bear-queen’s realm. Lips sticky with honey, I talked with birds and walked fearless into the troll-king’s sacrifice. Walked out of it alive, too. The crows pulled those memories from me, gave me peace to live in this world where magic means bare glimpses and passing moments, never a lasting magic over the whole land. Now that my memories have returned, that peace has left me.

The queen may be dying, but surely the magic still lingers in her land.

How was it that I found my way to the world below in the first place? Water, birch, and blood. That’s it. That’s how to open the gateway. The crows told me, then, the magpies nattered about it, the jays repeated water, birch, blood.

The otherworld is calling to me.

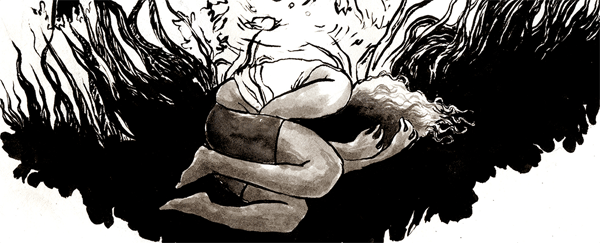

I go and find one of my father’s woodcarving knives in the shed. I slip back onto the jetty, the knife heavy in my hand.

"Spirits," I say, "people of the otherworld. Crows and magpies and jays, bring the bear-queen a message! I wish to come to your land again."

My words, although quietly spoken, echo on the water. The sky is lighter than the still, dark lake. I feel utterly alone. I’ve forgotten about my family in the sleeping houses. There is no one in the world except me by the lakeside. The birch-gateway stands silent and implacable beside me, its roots reaching into the water. The lake sings stillness to me.

I sit down on the jetty and slip my feet in the water. The lake’s depths tug at me, urge me to come below, to let go, to find the magic again.

The first time I went there half by accident–when swimming, I slipped on a sharp rock, felt them calling. The water, the blood from my foot, and the birch-gateway’s power, they brought me foundering into the otherworld.

If I just cut myself a little bit – just a little nick, just a trickle of blood – that might be enough to open the gate. I might be able to bid the queen farewell.

My body feels numb; my brain is wrapped in a deep blanket of grey. Somewhere I wonder if what I’m doing is wrong. There is a family to love and take care of. I have a wife, I have a son. But the memory of magic is calling me.

I press the knife to the palm of my hand.

I hear rustling movement in the massive birch above me. A bird-voice calls: "It will not open. It will not open." And a moment later, mournfully, "The queen is dead. The queen is dead."

A vision flutters into my mind: the bear-queen surrounded by mourning flowers, devoid of breath, of life. Her bier is ringed with white stones like the one that the magpie brought my son. The queen is dead, and I didn’t get to say goodbye. My chest feels tight, my eyes full of tears that won’t fall. Loss grips me in a vise.

It will not open. Does the queen’s death mean I can no longer sink into the otherworld? But the birds can fly to and fro, even bring me a stone from the queen’s being-built cairn. Could I not go back? Just for a moment? Couldn’t I return to the world where magic glimmers as a spark within every living thing, within the land itself? I want to shriek my loss into the waiting lake. Loss of place as well as loss of a person I loved, all those years ago.

I almost throw myself into the lake, almost slice my hand open. But then I remember what the bear-queen said to me when we parted. Find the magic in your own world, small one. Be brave and live.

I stare at the knife in my hands with sudden horror. Even if I could get to the otherworld, I have no idea how to get back without the bear-queen’s power. Maarit would think I’d committed suicide, she’d be broken apart. Kristian would lose one of his parents.

The knife clatters from my fingers onto the jetty next to me. In this world, magic is hard to find. But I have to be brave now.

I lower myself into the water. I go under and swim a few strokes in the dark, cool depths. I come up next to the jetty, gasping, grasping its wooden planks for grounding. I clamber back up dripping.

"Goodbye," I say to the bear-queen. She can’t hear me. My voice can’t even reach the other side of the lake, let alone another world. Just then a jay swoops above me and whispers goodbye, goodbye. I try to follow its flight but the birch tree throws shadows in my eyes. After I blink, the bird is gone. Is it taking my greeting back to the otherworld? My heart beats with hope.

As I walk back to the sauna building, I can hear the crows talking. Craww, craww. Almost, I can understand them.

Tomorrow I’m going to tell Maarit everything.