In Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, the poet John Shade’s daughter drowns herself, and later he suffers a blackout, during which he has a vision of a fountain. He reads in the papers about a woman who saw a fountain during lifesaving surgery. He’s elated, feeling that this shared vision proves the existence of life after death. He contacts the journalist, who tells him it was just a misprint—the story was meant to read “mountain.” “Conscious… that his very quest to explore the beyond makes him seem a mere toy of the gods,” Brian Boyd writes, “[Shade] derives a sense of the playfulness hidden deep in things, and feels that he can perhaps understand and participate a little in this playfulness, if only obliquely, through the pleasure of shaping his own world in verse, through playing his own game of worlds.” That is, through artifice.

Blade Runner 2049 references Pale Fire a number of times: we see a copy of the book in one shot, and Robin Wright’s character Joshi quotes it, too. Her replicant replicant-hunter K/Joe (Ryan Gosling) tells her about a memory that he already knows is an implant, of a toy horse he hid from bullies in a furnace. But in that Dickian way of about-faces and circles within circles, the sequel to a story about a human who might be a replicant is a story about a replicant who might be a human, or almost. An information blackout sends K on a trail that leads to the furnace where he finds the toy horse. The memory was real, he therefore is real, in the sense that the film defines it—born and not made. But later, the replicant rebel Freysa (Hiam Abbass) tells him he’s misread a meaning into what was just a diversionary tactic of the fugitive replicants Deckard (Harrison Ford) and Rachael (Sean Young). Though the memory is real, it’s not his; it’s the memory of the true-born replicant Ana. He is downcast to learn that he's not special, but persists in saving Deckard all the same.

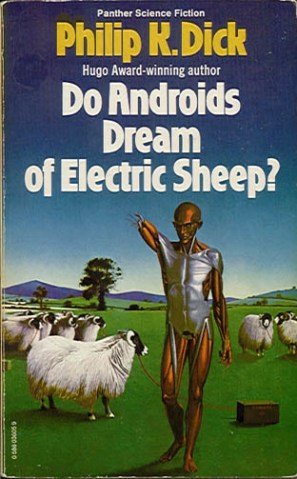

In Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut, Deckard has a reverie of a unicorn. His colleague Gaff (Edward James Olmos) makes an origami unicorn that he leaves at the door to his apartment, instead of coming in and retiring Rachael, if not Deckard as well. The unicorn reverie could’ve been an implant or just a coincidence—Deckard half smirks, half nods, then makes his escape. The point seems to have been not so much what Deckard “really” was, but how tenuous any identity is at all (in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which the film was based on, Deckard starts questioning his identity over merely a faked video call).

In Do Androids Dream…, a new religion called Mercerism has sprung up after World War Terminus and the mass extinction of nearly every species on the planet but humans. Followers use an “empathy box” to watch and then “become” an old man, Wilbur Mercer, forever climbing a mountain, pelted with rocks whose sting the user feels. Empathy in extremis, leading to fellow-feeling with all other humans. Androids go on to expose Mercerism as a con; Wilbur Mercer turns out to be a drunk shambles of a bit-part actor—and yet this doesn’t change people’s response to it.

The sentimental take on all this: it’s a testament to the spirit, whether human or otherwise, to keep going even when your raison d’être has been proven false. A better take: the raison d’être must be capable of being proved false to be worthy of following.

Interlinked

Interlinked

Nabokov is a dangerous touchstone, and referencing him the artistic version of an argument from authority, the kind of habit he himself parodied via the title of his novel and fake poem that leaned so conventionally on Shakespeare: “Help me, Will! Pale Fire” (this references Timon of Athens). At worst, it can be a warning that a story has pretensions far above its pay grade (the only successful Nabokovian story in recent times being the Darin Morgan X-Files episode “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space”.) Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriters Michael Green and Hampton Fancher have set themselves a high standard, tempted fate, and the results are predictable.

2049 has a clear-cut bad guy for us to revile in the form of CEO-god Niander Wallace (Jared Leto), introduced giving a monologue and dispatching an underling in the style of a Bond villain; Wallace also threatens the iconic Deckard himself with torture. This torture needs to take place off-world so the plot can give Deckard the chance to be rescued from Luv (Sylvia Hoeks), Wallace’s replicant henchwoman. A few scenes before this, she destroyed the hero’s hologram girlfriend—but Joe avenges his Joi (Ana de Armas) in a drawn-out superhuman martial arts fight, as disappointing a choice of climax as the same one Michael Green came up with for Alien: Covenant.

Disappointing, because the Blade Runner story in its various iterations has always been so much more than Screenwriter 101 tricks to generate sympathy. The story is about—the story is empathy.

If only you could’ve seen what I’ve seen with your eyes

The original film complicates empathy enough that it asks us to feel for a cop who executes runaway slaves, then tilt towards feeling in the final act for a homicidal Aryan android. In the sequel, despite the presence of the merciless Luv, we’re asked to feel squarely for the replicants, reduced now to a revolution-in-waiting over their merciless human overlords.

In Do Androids Dream…, though, empathy is not black-and-white, or a touchy-feely panacea; it’s necessary for being human, but not guaranteed. Humans might have developed Mercerism (whose association with “mercy” is not accidental), but even so, the concern of Deckard, a follower of Mercer, for his wounded fellow bounty hunter Dave Holden, is immediately tainted with ambition. The character J.R. Isidore (the basis for the original film’s J.F. Sebastian), gets treated kindly by his boss Mr. Sloat, but the moment they suffer a professional snag, Sloat turns cruel. And when Deckard feels sorry for Isidore having to witness animal torture, he refers to him, even despite his empathy, as a “chickenhead” (the derogatory term for “specials”—people who have remained on Earth after World War Terminus, and are thought to have distorted genes due to the radioactive fallout).

The book is deeply ambivalent, too, about how much empathy we should have towards its androids, performing Dick’s own complicated ambivalence towards them. A perfect dramatisation of this is when Deckard sleeps with Rachael—which, given the book was written in ’68, might well be one of the earliest “sex with an android” scenes around. As written, it’s either a failure to subjectify Rachael, or—to allow that its form might be following function—is your trashy ogling SF sex scene that objectifies by convention but also according to the story’s theme:

“She unbuttoned her coat, carried it to the closet, and hung it up. This gave him his first chance to have a good long look at her…the total impression was good, however. Although definitely that of a girl, not a woman. Except for the restless, shrewd eyes.”

In that typical noirish way, their having sex leaves Deckard angry at himself. His self-hating response to his depressed wife has been to “use” Rachael, all the while deriding her lack of true consciousness.

Dick explicitly compares replicants like her to antebellum slaves, yet the master’s religion is not available to these slaves because of their built-in defect: they cannot empathise. Do those who can’t show empathy still deserve it? Then again, who does? Then again, what does? When is empathy just projection, or anthropomorphism? And what if our fear of being accused of anthropomorphism was just a way to avoid the possibility that personhood might be more than a binary?

Everybody needs good neighbours

Do Androids Dream… is intelligent enough to go far beyond questions of what is artificial about the human and human about the artificial. The book is more lateral: it depicts four distinct forms of life: human, mutant, android, and animal. Fittingly for an author whose middle name is “Kindred,” Dick's categories are not all equivalent, but neighbours in personhood (Isidore: “It’s good to have neighbours.”) Rather than projecting ourselves on to the inner lives of others, “recognising their humanity,” empathy might be about having this broader sense of personhood. At the same time, the book does not expect our responses to all of them to be the same.

J.R. Isidore, its unwitting moral centre, is glad to have made friends with androids despite their lack of empathy. Without them, he would feel like an electronic appliance:

“He entered Pris’s former apartment, unplugged the TV set, and detached the antenna. The silence, all at once, penetrated; he felt his arms grow vague. In the absence of the Batys and Pris he found himself fading out, becoming strangely like the inert television set which he had just unplugged. You have to be with other people, he thought. In order to live at all. I mean, before they came here I could stand it, being alone in the building. But now it’s changed. You can’t go back, he thought. You can’t go from people to nonpeople. In panic he thought, I’m dependent on them. Thank god they stayed.”

Isidore’s kindness towards the replicants, his need for their company, and the fact that he falls in love with one of them, Pris Stratton, shows he can easily resist binary thinking. In Mercer’s terms, he’s a “highly moral person.” His empathy stretches across the full continuum of what is and what isn’t human; more accurately, it’s an inclusive, plural empathy, existing without judgement. And Dick being Dick, he makes the person who’s capable of this ostensibly inferior to everyone else. This empathetic everyman is a recurrent figure in his work—a reminder that social status and morality, in Dick's worldview, have nothing to do with one another.

Deckard begins the book with fairly unnuanced feelings towards androids: he hates them—obviously useful for a man whose job it is to exterminate them. The persistent, reliable android failure at the Voigt-Kampff Empathy Test (iterations of which are used in both films) and at embracing the empathic religion of Mercerism sustain this hatred:

“An android, no matter how gifted as to pure intellectual capacity, could make no sense out of the fusion which took place routinely among the followers of Mercerism—an experience which he, and virtually everyone else, including subnormal chickenheads—managed with no difficulty.”

Deckard goes as far to say that “evidently the humanoid robot constituted a solitary predator”—although the humanoid robots he says this about are, of course, escaping slavery, so it’s not quite that simple. In his 1975 essay “Man, Android and Machine,” Dick says of androids that: “their handshake is the grip of death…their smile has the coldness of the grave,” and they’re “a cruel and cheap mockery of humans for base ends”. Yet when Deckard kills Luba Luft (Zhora Salome in the original film), and discovers he has unsettling, complex feelings for Rachael, his stance shifts:

“Rick said: “I’m capable of feeling empathy for at least specific, certain androids. Not for all of them but—one or two…So much for the distinction between authentic living humans and humanoid constructs.”

This more expansive notion of empathy develops throughout the book. At one point, Pris says: “the androids are lonely, too,” inviting our empathy, and still Deckard, just like Dick, resists—he feels that his new ability to care about androids makes him feel that he is “violating his own identity.” Even so, he’s in too deep. He asks himself “do androids dream?” investing them with the facility for that most mysterious of human behaviour; Rachael says she has empathy towards Pris; and then Rick himself confesses to loving Rachael. Both Dick and Deckard’s resistance breaks down: empathy matters more.

About Rachael in particular, immortalised by Sean Young’s sad eyes and pompadour hair—there’s a current of thought in Dick scholarship that plays psychoanalyst with the recurrence of the “dark-haired girl” character in his novels, and also in real life. He even openly admitted he was fixated on this kind of woman. In Do Androids Dream…, this “dark-haired girl” is Rachael and Pris (in his 1972 novel We Can Build You, which can be read as a prequel to Do Androids Dream…, it’s Pris). The theorist N. Katherine Hayles puts forth the semi-convincing theory (depending on how much personal context you care to inform your reading of novels—your mileage may vary) that the “dark-haired girl” is the screen upon which Dick projected his complex relationship with both his mother and his twin sister, Jane, who died when she was six weeks old. His mother was emotionally cold, causing Dick anxiety; while the loss of his twin sister catalysed a lifelong obsessive grief. As Hayles says: “Dick intuited that in some sense he continued to carry this shadowy Other within his body, a figuration that reflected the fact that Jane no longer had an autonomous existence apart from his imagination of her.”

Rachael and Pris (arguably) perform Dick’s complex relationship with his mother and sister. Pris is what Hayles calls the “schizoid android,” the bright, cold and emotionally distant “dark-haired girl” who embodies the negating qualities of his mother. Rachael, though, is capable of empathy and possibly even of love. She is the dark-haired girl to whom both Deckard and Dick can relate. In this way, she explodes Deckard's binary sense of reality by not acting entirely as an android is expected to act; by not being entirely what an android is meant to be. Where might Dick have got the notion of empathising with, and feeling connected to, an unreal Other? If you’re looking for a psychological explanation for at least one aspect of Dick’s compulsion to connect beyond binaries, it’s right there.

It’s also curious that in 2049, Villeneuve introduced the idea of twins, a boy and a girl; only this time the girl was the real one, and the boy, the unreal Other. Was this a nod towards Dick’s own obsession with twins, or just a coincidence?

Beyond Rachael, though, empathy overrides categorical thinking and exceeds stable identities—Dick might protest otherwise, but he always succumbs to this more expansive vision. He also argues that the distinction between man and machine is collapsing, anyway—in “Man, Android and Machine,” he says:

“The greatest change growing across our world these days is probably the momentum of the living toward reification, and at the same time a reciprocal entry into animation by the mechanical.”

He genuinely believed that humans were becoming more machine-like, that we would all soon merge. As Donna Haraway said just nine years later in A Cyborg Manifesto: “We are all chimeras, theorised and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism. In short, we are cyborgs.”

The fact that, for Dick, the dividing line between machine and organism is blurred means that Ana, Deckard and Rachael’s daughter in 2049, is perhaps symbolic of the inevitable—and maybe not even the inevitable, but the already-has-been. In his 1972 essay “The Android and the Human,” Dick reminds us that only in modern civilisation do “animated” objects seem absurd; prior to this, a more monist, pagan or panpsychist approach, where objects contained a spirit, or a sense of life, was considered entirely sane. Transposing such a view to modern machines is not new, then—it just resurrects a old belief. As Dick says in “Man, Android and Machine”: “we hold now no pure categories of the living versus the non-living; this is going to be our paradigm... one day we will have millions of hybrid entities which have a foot in both worlds at once.”

But the films inspired by the book are not so visionary. 2049’s binary thinking, like that of shows like Westworld, is one reason they portray their replicants as easily far more worthy of empathy than corrupt old humans (to truly challenge our capacity for empathy, androids should not be played so humanlike.) The film depicts worse and better replicants. Despite some sympathy for the rebel cause, Luv (whose naming, alas, misses out on “Captain Darling”-style jokes) is Terminator-relentless in the pursuit of her maker’s commands, wanting to prove, as she shouts at one point, that “she is the best”—do androids dream of Electra complexes? And gone are the complicating fascist superman tones of The Director’s Cut—the replicants that appear out of the sump at the end of the sequel are conspicuously diverse. Meanwhile, Ryan Gosling goes from state executor to self-sacrificer, in the familiar Hollywood trajectory.

Why did the filmmakers return to the binary rather than Dick’s more complicated schema? A chilling proposition: the age-old human urge is to divide the world into only two camps: worth caring about and not.

What Joi

The sequel understands how replicants will end up using their own replicants—how they themselves will enter the game of how much empathy they ought to have for mass-produced entities of ambiguous personhood. In the book, Rachael empathises with the rest of the types of which she is just another version (though her lover, Deckard, is annoyed by her mawkishness…). In 2049, Joe has his own reproducible romantic partner, Joi.

Here, we’re meant to empathise with Joe’s loneliness—it’s clear Joi is his only source of intimacy. But Joi is also the nth degree of pornography, forever modifiable yet interchangeable, and, as if this design philosophy has leaked into the general girlfriend experience, a fantasy of support, concern, and self-sacrifice. Is this a chauvinist fantasy of a Stepford Wife? Or an improvement on the misogynist fantasy of a sex toy/slave with a handy four-year lifespan? Is their relationship reciprocal, at least? Well, Joe gives back to Joi, first giving her a simulacrum of touch, which he himself cannot receive from her. She returns the favour another way, simulating sex with him by transposing her virtual self over the real body of a sex worker (who will later turn out to be artificial, too, an updated vision of the replicant Pris from The Director’s Cut, who in the book was herself a clone of Rachael—this, presumably, was changed in the film to avoid confusion). This replicates the sex-scene-by-proxy in Spike Jones’ Her, without the latter’s ironising awkwardness; Joe and Joi's relationship is noble. He buys her as much independence as she can get, and she uses it to try plead for his life.

Given that Joi is a Wallace corporation product, it’s sad that even Joe’s solace is a mirage created by his antagonists. A replicant can harness a manic pixie dream hologram to his lonely ends, but as he does so, he treats a sex worker as a shell to be filled by a make-believe woman; and he pins his dreams and desires to a piece of standard-issue Wallace merchandise. Relief, brought to you via surrogates and evil billionaires. (Villeneuve probably just intended us to empathise with Joe, but you should always be careful about what kind of consolations you give your lonely men…).

Not you, I mean me

In the new film, Wallace complains that he can only make so many replicants. But inspired by this passage of Rachel’s dialogue in the book, 2049 offers him an opportunity:

“Androids can’t bear children—is that a loss?… I don’t really know; I have no way to tell. How does it feel to have a child? How does it feel to be born, for that matter? We’re not born; we don’t grow up; instead of dying from illness or old age we wear out like ants. Ants again. Not you; I mean me.”

K finds in a piano evidence that Rachael got to find out what it was like to have a child, in the shape of a dusty piece of infant clothing (“for sale, baby sock, never worn??”). For the rest of the film, he grapples with the question of “how does it feel to be born?”—it feels better, it seems, than to have been made. Wallace, too, hunts down the evidence of this miracle, in order to create a self-reproducing workforce to conquer the stars. Wallace wants hereditary slavery.

You can rely on mysteriously omnipresent Jared Leto to be terrible in this role (according to reports he stayed in character between scenes. Perhaps he’s still in character) but he does have the job of outlining the sequel’s notion of personhood: speciation. Some replicants can now make babies.

Robin Wright’s character cites the ability to reproduce as the crucial distinction between humans and replicants. (The film is weirdly pro-life in this sense, similar to how, in the book, not only does the human race make animal rugs and fur illegal, but abortion too—nothing is not complicated in the world of Philip K. Dick). But Mother Rachael is dead at the beginning of the film, leaving Deckard as the quarry, possibly as some kind of prize stud—the whole story was about the highest-paid actor after all. Poor Roy, Pris, Zhora and Leon, downgraded to a subplot in a miracle birth narrative. Screenwriters, stop and think if you have anything interesting to add to the Bible mythos! The very title of the novel should have given the writers a hint at what else they could've done with the story.

Dick wanted to know whether androids dream of electric sheep; The Director’s Cut asks whether humans (and possibly replicants) dream of unicorns; in 2049 we find out that replicants dream of wooden horses. But to dream can also mean to yearn. What if replicants, just like humans, were anxious about wealth and status symbols? What if they even replicated our corporate-taught fantasies about love? Yet while foregrounding Joe and Joi, 2049 also undercuts the beauty of the Deckard and Rachael love story. Instead of Deckard and Rachael running away together despite her dying in four years’ time, and him maybe doing so, too, they’re both revealed to be longer-lasting Nexus models. Eldon Tyrell was lying when he said he couldn’t give more life (fucker).

In memory of a real tree

Tyrell built the replicants, “but not to last.” The facts of life: everything dies. The landscapes of the sequel are the “tomb world” described in the book, but its death theme is more about the macro-climate than the personal or animal. The dead tree at the start of the film is symbolic—someone has left a recently alive flower at its root because it's also a grave, one that contains evidence that life has found a way (again).

Animals are crucial to the book. The mass extinction of nearly all animal and plant life has turned Earth into practically a wasteland—a “void”, Isidore calls it. Owls started dying out first; in the original film, an owl is one of the first animals we see. But strangely, the film reverses what kind of owl it is (“Is it artificial” / “Of course it is.” / “Must be expensive.” / “Very.”) The artificial owl is a symbol of wealth, but in the book, it’s the vanishingly scarce real bird that’s the ultimate luxury item.

The “cells interlinked within cells interlinked” of the sequel’s new, scarily hyper and automated Voight-Kampff style test—or baseline test—comes from the poem in Pale Fire: its meaning is no longer to be openly read, but something to be decoded. Though animals feature in the first film’s test, in the book, the topic of animal cruelty is much more apparent in the questions. Such “enlightened” attitudes towards animals, however, only serve to highlight how graded human progress always is—how each generation, in its smugness about what they have now allowed into the scope of moral consideration, still disregards at the same time another class of living things—in the book’s case, androids.

The reason animals are essential is because they are the closest analogue for androids—they, too, are less human than humans. Humans yearn for these animals with which, now that they're mostly extinct, they’ve formed a deep spiritual connection. So even in this mild sense, which borders on sentimental nostalgia, humans have evolved—and yet these same humans still execute their slaves. And these same slaves, who we might feel sorry for, torture animals (or insects, at least). In one of the book’s final scenes, J.R. Isidore’s new neighbours take the precious spider that he’s found and cut off its legs one by one with scissors. Dick chose a spider because it’s not cute. Nor does the torture ennoble the spider; its suffering is gross and pathetic. The scene is testing the reader. Yes, it might be horrific—Isidore’s helpless anguish, his pointless empathy—but if we are shocked at what Pris does to the spider, shouldn’t we feel the same about what Deckard does to the androids?

The book’s precious animals, and its humans’ over-investment in them (let’s not forget, Deckard takes on his entire android-killing mission, from beginning to end, so that he can afford to buy a real sheep), is an entertaining form of post-anthropocentrism. Humans aren’t necessarily the most important thing in the world anymore—in Dick’s world, animals rival them. This was more likely a clever dystopian contrivance on his part rather than biocentric propaganda, but it has an uncanny relevance to today’s post-human currents of thought (Dick has an uncanny relevance to everything, it seems)—and in negating human exceptionalism here, he’s, intentionally or not, issuing a warning to the anthropocene, way back in 1968.

The final animal in the book is the one Deckard finds when he falls into the hell-vision of the tomb world where everything is meant to be dead. Even there, Deckard finds life, in the form of a dusty old toad. But when he gets home to give it to his wife, she discovers that it’s artificial.

It won’t matter.

It's not the same but almost

The tension between the real and the artificial was always the least interesting place a new Blade Runner story could have gone. Especially when that binary is so evaluative, with the almost-real or the as-good-as real made to feel like a tragic compromise: “it’s better than nice, it feels authentic, and if you have authentic memories you have real human responses. Wouldn’t you agree?”

This line, said by the “real” miracle replicant Ana, is another example of modern films giving away their ethos inadvertently through dialogue (e.g. the comforting regression contained in The Force Awakens’ “Chewie – we’re home.”) In a vertiginous postmodern way, the film itself wants to be real, to be authentically Blade Runner, whatever that means. Composer Jóhann Jóhannsson left the film because his score didn’t mirror Vangelis’s as much as was desired (Vangelis is still alive and working, you know). Which itself is odd, considering how un-Vangelis the final score ended up being; no saxophone, no half-synthesised/half-honky-tonk piano, very little twinkle: instead, sound-stretched versions of the original melodies with what sounds like Hans Zimmer yelling a parody of his signature sounds into a vocoder.

One story goes that Blade Runner, whether in the Theatrical or Director’s Cut, is only a technical or visual achievement. A lot is buried in that “only.” How can the early work of Ridley Scott, with every frame dense with intelligent detail, be put in the same style-over-substance category of the haute music videos of Tarsem, or the cod-David Fincher of prestige TV? Slick Denis Villeneuve has no knack for this production design clutter, for what Dick called “kibble”; the city scenes are weirdly clean and uncrowded at street-level. He’s more comfortable with the simple stark contours we get in Wallace’s castle and Ana’s dream laboratory. His style is more expressionistic, too, than Scott’s—at times the film has the 90’s design aesthetic of Brazil or Delicatessen—the labyrinthine refinery and junkyard sets, the overhead shots of an endless dark Los Angeles with glowing trenches of favelas.

The best example of the desire to authentically replicate some essence of the original film is the climax’s use of a CGI Sean Young as the younger Rachael from the original film. Mazin wrote before that we were still in the uncanny valley but climbing up a slope; in 2049, we’re over the hill. Either this truly spectacular special effect is the triumphant and on-theme collapsing of the pointless binary between the artificial and the real, or it is the final seal of modern cinema’s desperation for lifelikeness above all.

For Dick, artifice-as-artifice was worth our time thinking about, and in a way that went beyond extending our empathy to the artificial, putting it on a par with, if not equal to, the natural. Perhaps our empathy actually depends on a kind of artifice.

In Do Androids Dream… empathy is ostensibly “disproved.” The androids reveal that Mercer is an actor, paid in whisky, that the whole empathy box experience is based on a lie. But, in one of the most beautiful and moving passages in any genre, Dick writes:

“Is the sky painted?” Isidore asked. “Are there really brushstrokes that show up under magnification?”

“Yes,” Mercer said.

“I can’t see them.”

“You’re too close,” Mercer said. “You have to be a long way off, the way the androids are. They have better perspective.”

(Can we even imagine a story where Truman hits the painted wall of reality and returns, happy?)

“Is that why they claim you’re a fraud?”

“I am a fraud,” Mercer said. “They’re sincere; their research is genuine. From their standpoint I am an elderly retired bit player named Al Jerry. All of it, their disclosure, is true. They interviewed me at my home, as they claim; I told them whatever they wanted to know, which was everything.”

“Including about the whisky.”

Mercer smiled. “It was true. They did a good job and from their standpoint Buster Friendly’s disclosure was convincing. They will have trouble understanding why nothing has changed. Because you’re still here and I’m still here.” Mercer indicated with a sweep of his hand the barren, rising hillside, the familiar place. “I lifted you from the tomb world just now and I will continue to lift you until you lose interest and want to quit. But you will have to stop searching for me because I will never stop searching for you.”

Empathy depends on authenticity not meaning anything. In the tomb world—that more and more familiar place—a storied kind of identification occurs: Deckard is Isidore is Mercer, who is an actor. The point here goes further than how it doesn’t or shouldn’t matter that Mercer is artificial—for example, Isidore still wants and needs the androids’ company even though he knows they’re exploiting him. Mercerism's artificiality forces it to collapse in on itself, but it remains a genuine experience—so perhaps it must contain the possibility of the artificial in order to work. The worthiness of empathy like Mercerism is that you can never know the other—we are all theoretically replicants to each other, inner-lifeless and soulless. In that sense, empathy is “taking a chance on someone”, “giving them the benefit of the doubt” and all those other hoary humanistic virtues.

What else collapses, or ought to collapse, the real and artificial, in order to make us feel for what’s not really there? Fiction might be our empathy box. In books, poems, games, films, watching then becoming others, and so identifying with the real plight of made-up characters. The spider, and the spider’s carer, Isidore, who the reader empathises with so keenly, are not really there either. They’re both simulated living things—replicants, even.

Fiction forces you to empathise by working on your natural tendency to read agency into the inanimate. Empathy, meanwhile, is itself a kind of fiction, too—you can never know what it’s like to be someone else, never walk in another’s shoes, never be Mercer climbing up that mountain, not “really.” Literal empathy is impossible, and yet it happens in fiction all the time. Empathising with characters in a story is a sort of purposeful conceptual mistake.

Might empathy have begun as a kind of mistaking of identity, like that between real and implanted memories, between fountains and mountains? Is that how it evolved? Did the imaginative capacity needed for language—“What do you mean?”—entail some brief and minor confusing of yourself with the other—from which neurological side-effect came all moral and spiritual feelings of brother/sister/otherhood? Because the ancestor of “what do you mean?” surely had to have been “what do you feel?” Our feelings are how we experience the physiological preparation for actions that we might be about to do. To work out what another creature might do (do to you), we first had to learn how to feel what they felt. Using “I feel” interchangeably with “I think” and “I believe,” as we do, isn’t a symptom that we’re dangerously mixing up emotion and reason.

Empathy regardless of artifice—and artifice in the full Dickian scope: artificial animals as well as humanoids, and made-up characters—is what fiction gets us to practice. Our empathy for fictions is meaningful despite/because of fiction’s fictionality. (It is mature, healthy, to cry at a tragedy; for now, it’s deluded to cry over a broken toaster; but considering our relationship to pets, it seems inevitable that one day we will mourn and weep the death of machines.) In a way, all empathy depends on make-believe, as opposed to knowledge or certainty of what the other is or isn’t. Yes, we can never know what it’s like be a bat, but a moral imagination is just that, imagination. When I was younger, I once saw a bat that a boy had knocked out of the sky with a boomerang. Its wing was sliced almost off at the armpit. The blood was purple. Its chest moved up and down fast as it lay in the boy’s hand; he then tied its wings in a knot to stop it from escaping. I didn’t know what it was like to be that bat, but I could imagine how it felt. My imagination wasn’t a mystical connection between beings, nor an apprehension of a true fact. It was just a story, but one that told me what I should’ve done—not left the bat to the boy’s mercy but killed it as soon as he turned his back. Had he turned and said that I didn’t know whether the bat was real, or what it felt, or whether it could feel anything at all, wouldn’t that have been as psychopathic as somebody who could say the same thing, with just as much grounding, about a human?

Does it matter whether my story is true?

Ensemble: “all the parts of a thing considered together”

If it doesn’t matter who is “really real” or not, whether Joe or Ana was the miracle replicant “twin,” then upon finding out that he wasn’t the one, Joe should have behaved even more like he was—failing a second brainwashing “baseline test” even more drastically than the first time.

In A.I. Artificial Intelligence—a huge influence on Blade Runner 2049, with dirty-bombed Las Vegas twinned with statuesque Rouge City—the capacity to dream, this time absolutely meaning “yearn” as well as “imagine”, is what drove robot David to the end of his quest, and what, in his creator’s eyes, makes him a real boy. But upon learning that he’s still not as real as his biological archetype, the creator’s true-born son, David throws himself off a building. When the rebel replicant breaks the news to special Joe that he’s just replicant K after all, he—barring a brief shock—keeps trudging along the same preprogrammed course of action he was always on. (Boyd again: “It is not that deflating recognition, however, but the resolve that follows it, that forms the core and key to the poem.”) The core of 2049: I am the chosen one, I am not, they are, well, I can still be useful; then our hero dies after reuniting the real chosen ones, Miraculous Father Deckard and Miraculous Daughter Ana. Perhaps K stepping back from being special and willingly making himself useful to others is the kind of anti-narcissism that Dick would've admired.

The narcissist believes that they are the main character in life’s story, and others are bit-players, supporting actors (there only to support, their own lives just an act). To empathise, though, is to feel like everyone is the main character, that existence must be an ensemble piece, that everyone is a chosen one; and that we have accountability as well as agency. One thing we have to choose, then, is whether we want to live by this story—that all of us are accountable to anything we feel can feel.

Note:

The title, “it will prove invincible,” is taken from a letter Dick wrote on seeing a preview of Blade Runner. As he says: “My life and creative work are justified and completed by Blade Runner.” He never got to see the final film—he died on March 2nd, 1982; it opened on June 25th the same year.