In attendance:

- adrienne maree brown is the Co-Editor of Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements and the upcoming Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds.

- Nino Cipri is a queer and nonbinary/trans writer. A multidisciplinary artist, Nino has written fiction, essays, reviews, plays, comics, and radio features, and performed as a dancer, actor, and puppeteer. One time, an angry person on the internet called Nino a verbal terrorist, which was pretty cool.

- Charles Payseur is an avid reader, writer, and reviewer of all things speculative. His fiction and poetry have appeared at Strange Horizons, Lightspeed Magazine, The Book Smugglers, and many more. He runs Quick Sip Reviews, contributes as short fiction specialist at Nerds of a Feather, Flock Together, and can be found drunkenly reviewing Goosebumps on his Patreon. You can find him gushing about short fiction (and occasionally his cats) on Twitter as @ClowderofTwo.

- Carlos Hernandez is the author of The Assimilated Cuban’s Guide to Quantum Santeria (Rosarium 2016). By day, Carlos is a CUNY Associate Professor of English, with appointments at BMCC and the CUNY Graduate Center. Besides his dedication to writing, Carlos is a game writer and designer: he served as Literary Consultant for the forthcoming iPhone game Losswords and continues work as a designer and lead writer on Meriwether, due out later this year.

- Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person who's recently become a resident alien in the U.S. E writes both fiction and poetry, and eir work has been published in a variety of venues like Strange Horizons, Clarkesworld, and Apex, among others. E reviews diverse fiction, poetry and nonfiction at Bogi Reads the World. You can also follow em on Twitter at @bogiperson.

- Troy L. Wiggins is a writer and editor from Memphis, Tennessee. His short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Griots: Sisters of the Spear, Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction From the Margins of History, Expanded Horizons, Fireside Magazine and Memphis Noir. Troy is Co-Editor of the Fiyah Magazine of Black Speculative Fiction. Troy lives in Memphis with his wife and their two dogs.

Nino Cipri: This is a roundtable about collective resistance, but let’s talk about the idea of “resistance” in fiction in more general terms first. What kind of trends do you see? What’s good? What’s problematic? What makes your heart sing, and what makes you side-eye a story?

Charles Payseur: Resistance, to me, is about systems. About corruption and fighting against it. So resistance in SFF can be about institutional oppression or imbalances in power and trying to counteract that. For me, stories that are about resistance have to be about more than just fighting against a bad guy, more than just revenge, or even a quest. They are about the ways that social systems are used to promote inequality and injustice and about how characters fight against the pressures to conform, ignore, or succumb to those systems.

I love stories that speak about resistance in terms of systems and information. An Owomoyela's "Unauthorized Access" or Malka Older's Infomocracy both do a great job of showing small groups of people and individuals taking on oppressive systems armed with information. Which speaks to me of a very realistic way of approaching resistance. If we've learned one thing from recent events it's that one of the greatest tools of corrupt systems is misinformation. Why else would there be a call to not fact check, and to "listen to both sides"? Why else would there be such a proliferation of "news sites" willing to claim the most outrageous and unsubstantiated things in order to try and sway opinion? These corrupt systems know that as long as they wash the truth in a sea of misinformation, many people won't be able to tell the difference, especially if they benefit from believing the lie.

As for what trends that make me hesitate to recommend a story? I am not a fan of stories that cast corruption as inevitable and inherent in humanity. Grit I can handle, but stories that paint humanity as inescapably exploitative, oppressive, and unjust with perhaps rare exemplars whose duty it is to save the wretched masses from themselves are not stories I tend to enjoy. Similarly, stories that insinuate that moral relativism is the same as immorality are stories that are probably going to strike a nerve. I believe in the power of humans to do good, even if time and again humans have shown that they are capable of great harm. I don't shrink away from Chosen One stories, really—I think that some, like N.K. Jemisin's "The City Born Great," are fresh and interesting and show a valuable, personal kind of resistance and survival and power. But I do tend to avoid Chosen One stories where the "hero" is disgusted with humanity and never really changes in that view.

adrienne maree brown: i have been thinking about this and looking for it, especially in this period where models of resistance and solidarity are so necessary. i have been rereading octavia butler's parables, ursula le guin's hainish books, samuel delaney's dhalgren, nalo hopkinson's midnight robber, as well as more recent work from nisi shawl, tananarive due, nnedi okorafor, and sofia samatar.

my heart sings when i see ideological diversity, family and pleasure amongst  oppressed people in fiction. so often there is a hero and there are the masses, huddled together in a constant state of struggle. when i read of characters laughing, making love, building family, or holding nuanced and well-presented contradictions, i get excited. that is how my life is as a fat black queer woman in glasses -- i have lovers and disagreements and nontraditional family and so much laughter and pleasure in my life, even as i collaborate with others for liberation.

oppressed people in fiction. so often there is a hero and there are the masses, huddled together in a constant state of struggle. when i read of characters laughing, making love, building family, or holding nuanced and well-presented contradictions, i get excited. that is how my life is as a fat black queer woman in glasses -- i have lovers and disagreements and nontraditional family and so much laughter and pleasure in my life, even as i collaborate with others for liberation.

i side-eye stories where peoples' liberation and survival hinge on the personal awakening or superpower or singular skillset of one person. i will most likely continue to side-eye such stories until some superhero neutralizes global fascism.

Troy L. Wiggins: I agree with Charles. We do have to think in terms of systems when we talk about resistance in the sense of social progress. To be clearer, to me resistance is about fighting oppressive, authoritative, violent systems for the good of oneself and one's community, alongside one's community, using whatever means necessary to destroy that system. So there is a broadness of scope required when thinking about and trying to locate themes of resistance in SFF literature. For me, themes of resistance in SFF ring true when characters or a work seek to tackle self-maintaining institutional systems with deep roots and strategic processes designed to sustain injustice, similar to the systems that we face in our real world.

To that end, the fiction that I sought out this year overtly depicted and discussed issues like colonialism and violent systemic discrimination, and I specifically looked for stories where individuals or communities fought against those systems using what scraps of power they'd retained from oppression's constant assault while showing the very real toll that resistance can take on a body and soul. For me, these works are usually framed by my reality as a Black American man, and I seek out stories that reckon with these themes from an Afrocentric kind of viewpoint. One book in particular really knocked my socks off: Victor LaValle's The Ballad of Black Tom. Thomas Tester's struggle is as an individual against an  oppressive state, and his choice in dismantling this system is so fraught, final, and resolute. He's destroyed himself for revenge, but also for freedom, for people like him to never have to experience what he experienced. I dig this kind of grounded reality about the nature of resistance and revolution and have enjoyed it in stories like Nisi Shawl's Everfair, N.K. Jemisin's The Fifth Season, and Peter Tieryas' The United States of Japan.

oppressive state, and his choice in dismantling this system is so fraught, final, and resolute. He's destroyed himself for revenge, but also for freedom, for people like him to never have to experience what he experienced. I dig this kind of grounded reality about the nature of resistance and revolution and have enjoyed it in stories like Nisi Shawl's Everfair, N.K. Jemisin's The Fifth Season, and Peter Tieryas' The United States of Japan.

I am hesitant to enjoy stories that romanticize the process or outcomes of sustained resistance. Resistance can be depicted in a very simplistic way in SFF: defeating the intergalactic empire for reasons, or fighting against an evil witch-king because he's the enemy of all fair folk, and everything ends in a huge explosion. Hooray, the day is saved! But resistance, revolution, and reconstruction aren't simple individually or together, and the best SFF grapples with the ongoing messy, gray reality of getting yourself and your people free.

Bogi Takács: I would also like to emphasize the collective aspect of collective resistance. English-language SFF is often about the Campbellian hero's journey, of one lone person fighting against oppression, facing nigh-impossible odds and overcoming them. Everyone else is at best an ally, at worst a tokenized Minority Person whose only role in the narrative is to aid the protagonist. Even marginalized creators often end up following this pattern, and this is what mainstream publishing often explicitly demands. But successful resistance in real life means people working together, often people who are marginalized in different ways. I think that these narratives of individual triumph influence our thinking very deeply, and tend to push social justice discourse in a direction where the term "ally" becomes pejorative and a quasi-label for majority outsiders, even though in practice collaboration happens between people who are marginalized, just differently.

There has been an increasingly strong undercurrent in SFF against this trend, including entire themes such as spaceship found-family stories. They have existed for decades, as in Ursula K. Le Guin's 1990 novella, The Shobies' Story. But they have a newfound popularity, with many readers explicitly seeking out such work. Ensemble casts are not popular with many editors, but they are an excellent way of demonstrating collective resistance—a good example is Chameleon Moon by  RoAnna Sylver, one of my favorite reads this past year. Found-family stories—whether on a spaceship or not—mesh intuitively with QUILTBAG characters, and there are now works organized around this concept, like the Fierce Family anthology edited by Bart R. Leib. They also help with including disabled and/or chronically ill characters, while not depicting us as "burdens" in a more conventional narrative. If networks of interrelated characters are shown, it is easy to see how everyone has their contributions and needs in a shared struggle.

RoAnna Sylver, one of my favorite reads this past year. Found-family stories—whether on a spaceship or not—mesh intuitively with QUILTBAG characters, and there are now works organized around this concept, like the Fierce Family anthology edited by Bart R. Leib. They also help with including disabled and/or chronically ill characters, while not depicting us as "burdens" in a more conventional narrative. If networks of interrelated characters are shown, it is easy to see how everyone has their contributions and needs in a shared struggle.

Paradoxically, emphasizing #ownvoices, while having many advantages, can work against depicting collective resistance if we are not mindful of this specific issue. (#ownvoices is a term coined by writer and disability activist Corinne Duyvis, and it refers to writing characters who share the author's marginalization.) Successful resistance is usually not carried out by a homogeneous group of people who all have the same marginalization and no other marginalizations, but by a coalition of allies—each of whom might have a different experience of resisting, and a different role. For instance, Nalo Hopkinson's work (from her very first novel Brown Girl in the Ring onward) has frequently presented many differently marginalized people working together to achieve their goals. To depict this aspect of resistance, one needs to venture beyond the boundaries of #ownvoices by necessity. These works often have at least one main character who is #ownvoices on at least one axis, embedded in a diverse cast—showing how personal experience of resistance can inform narratives.

Carlos Hernandez: Charles kicked us off in exactly the right way: if we aren't thinking about systems, we can't even begin to discuss the idea of resistance. This is true in life—a resistance requires a system to resist!—and even truer in SFF fiction, as SFF's emphasis on worldbuilding means that readers and writers alike find system-creation to be among fiction's great aesthetic pleasures.

If we take the above as a given, though, I'd like to complicate the notion of "systems." I would like to posit the following:

- Systems themselves tend toward neutrality, even if they are born of extreme bias;

- Constituents battle in society for the control of systems, and therefore the ways in which those systems will be interpreted;

- All enforcement of systems is, in the end, local: that is, down to the level of the body.

Each point above could be the subject of a dissertation! I will quickly try to illustrate each and then tie it back to fiction.

1. The Satanic Temple in the United States has done an excellent job of leveraging the legal system so as to force the Christian majority to confront the prejudice inherent in laws that favor one religion over another. Thanks to the Temple's proposing that a statue of Baphomet join the 10 Commandments sculpture already on Oklahoma Capitol Building grounds, the 10 Commandments were deemed unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court.

This is an example of the neutrality of systems. Laws are always created with specific intentions that often have unintended consequences once they are introduced into both the legal system and the culture at large. Even when they are "working as intended," they still have to be enforced, which leads to my second point:

2. Every government is a "rightness machine." That is, every government creates a system—a machine made of laws, social mores, etc.—that it hopes the governed will allow themselves to be controlled by. They do so by attempting to convince the governed that it is right: right by the will of God, right by the principles that undergird the legal system, right by power, etc. Power in a society means one of two things: access and control over systems, or the ability to convince enough of the governed that those who control systems shouldn't. The first is a function of those is power, and the second is a defining characteristic of any resistance.

3. Leaders are assassinated with appalling frequency. They wouldn't be if assassination weren't such an effective way of weakening a government or a resistance. That's because there are no systems, really—there is only the aggregate collection of every person's actions in a society. Laws that aren't enforced become jokes, until suddenly, they are enforced again. Every arrest happens in the name of the law, but ultimately between individuals—the person(s) being arrested and the person(s) doing the arresting, for instance. In the end, moral and ethical codes, laws, social mores and all other "big idea" ways of thinking about life have to mix with the boiling stew of desire and ego and blood of the human body.

And this is why literature is the best way to discuss resistance. It isn't philosophy or a social science, as those disciplines abstract the human experience to do their vital, important work. But you know how, when you're cooking, some recipes ask you mix your dry ingredients separately from your wet ones? The "dry ingredients" of philosophy et al. will only culminate in a fully-realized cake after you combine it with the "wet stuff" of people and their bodies.

Nino: What’s the role of victory and defeat in stories of resistance? Do these stories need a happy ending, the toppling of oppression, or the defeat of the Big Bads? Related to this: do stories of collective resistance have to center on struggle and conflict, or can they reconcile different kinds of character arcs and journeys?

Charles: When dealing with stories that center resistance, victory and defeat are loaded terms. Indeed, in these stories I feel like the idea of an ending is loaded, because it imagines that resistance ends at a certain point. History and certainly recent events have proven that resistance isn't something that just ends. There can be victories, yes, but what I like most about stories that effectively center resistance (or maybe how I judge if a story about resistance is successful to me) is that the struggle doesn't go away. If anything, it becomes more important, more complicated. Many SFF stories that posit "victories" fade away when the oppressive system is dismantled, or the leader of the oppressors is removed from power and replaced. On a narrative level, it makes a lot of sense to treat these moments as the end, to give something that feels definite and satisfying. But a story that doesn't at least acknowledge the work yet to be done, even in the best of situations, is one that in my opinion fails in its scope and imagination.

To look at a book that I feel is a great example of resistance done right, Melissa Scott's Trouble and Her Friends looks at a small group of queer hackers taking on  an oppressive system and [spoilers] replacing that system with one of their own. And while this does represent the end of the novel, the characters are very up front about this not being the end, that now that they have fought for and earned some power and self-determination, their work truly begins. To make the system better and more just. To push to find a way that works for everyone. Similarly, Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed looks at what happens after the successful revolution. What happens after a group of people breaks away from an oppressive system and forms their own. The novel is wrenching in its portrayal of how easy it is to slip back into exploitative cycles, how difficult it can be to retain justice in the face of hardship, and also how important it is. The story ends with a victory of sorts, but with an eye on constant reform and participation and struggle.

an oppressive system and [spoilers] replacing that system with one of their own. And while this does represent the end of the novel, the characters are very up front about this not being the end, that now that they have fought for and earned some power and self-determination, their work truly begins. To make the system better and more just. To push to find a way that works for everyone. Similarly, Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed looks at what happens after the successful revolution. What happens after a group of people breaks away from an oppressive system and forms their own. The novel is wrenching in its portrayal of how easy it is to slip back into exploitative cycles, how difficult it can be to retain justice in the face of hardship, and also how important it is. The story ends with a victory of sorts, but with an eye on constant reform and participation and struggle.

As for whether these stories must center on conflict, on revolution. . .well. . .not really? I think stories about collective resistance are all about more than just the struggle, but in stories that feature resistance, every aspect of the story is influenced by it. Love becomes resistance. Survival becomes resistance. Especially in short fiction, the stories are not typically about toppling huge systems but rather finding ways to live, love, and hope when doing so is institutionally discouraged by the setting/government/society/etc. These are stories that look at smaller, more personal (but still extremely powerful and vital) resistance. Like Sam J. Miller's "To Die Dancing," these stories are not always about happy endings, but about provoking readers to examine their own place in oppression and resistance that is going on all around them.

Carlos: I remember reading once that Goethe became distraught whenever he contemplated writing tragedy—which is why, maybe, his Faust eventually goes to heaven. I say this to parry an idea that probably came to Western culture via Aristotle's Poetics and has caused misreadings and oversimplifications ever since: namely, that tragedy > comedy.

We need different stories for different reasons. We read to expand our visions, for moral development, to be delighted, for love of language, to understand others better, to understand the world and all its horrors more completely, to cultivate wonder, to learn how to write. There is a type of resistance fiction written to cultivate hope. In some situations, the book in someone's hand may be the only shred of solace in their lives. There is no way I would ever presume to tell anyone that the books that gave them a balloon-ride perspective on their otherwise shattered lives aren't "good enough" because happy endings are simplistic. Happiness strengthens and emboldens.

That said, I think the American reading public is addicted to sweets, so to speak. The fact that, even in this question, we can capitalize Big Bad and all know what we mean is indicative of a penchant for a certain kind of chocolate-frosted ending that we always want at the end of the meal.

And there's the rub: we need less of the same, and more of more. One of fiction's great powers is the ability to prepare us for the unimaginable. Different fictions offer different affordances. We don't always know in advance what we ne ed. A proper resistance reads widely.

ed. A proper resistance reads widely.

Cory Doctorow's Little Brother is, to my mind, a powerful novel that wears its resistance on its sleeve. It's full of tragic moments, such as when the teen protagonist is fricking waterboarded, but it is filled with moments of hope and community and personal agency. Its infodumps on how to leverage technology to fight oppression are so joyful, they recall to me Sufi poetry.

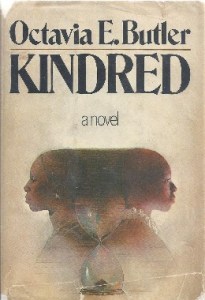

Contrast that with Butler's Kindred. Reading the novel through the lens of resistance makes its structure all the more fascinating: Dana suffers through some of the most monstrous violations that slaves in the United States had to endure. After a time, however, she gets to teleport back to 1976. She receives the means to maintain her perspective via her hopping between time periods (not to mention modern medicine)—an act of recharging that anyone involved in the work of resistance would be wise to remember. And while the past

inflicts a final grievous wound upon Dana's body, she becomes architect to her present by helping to forge her own lineage. It is a complex, disturbing, rending, almost impossible-to-read novel, so  harrowing is its plot. Yet it's one of the books I reliably assign when I teach Science Fiction, precisely because of its fruitful ambiguity.

harrowing is its plot. Yet it's one of the books I reliably assign when I teach Science Fiction, precisely because of its fruitful ambiguity.

Troy: I'm hesitant to think of a collective resistance attaining—or not attaining—whatever goals it had set as a blanket victory or defeat, just as I'm reticent to think that resistance and revolutions can ever really end, much less end in utopia. Of course, collective resistance movements in SFF can feel happiness when they defeat a Big Bad or win their freedom, but here is where most stories that tackle this idea stop—with the "happy ending"—because we like happy endings and we like beating Big Bad enemies and we like heroes who save the day. But there's still so much to do after that, working to rebuild and maintain what you've won. This invites conflict and struggle even though whatever was oppressing the resistance group is gone. There are many gray areas between victory and defeat.

The books in David Anthony Durham's Acacia trilogy do a fantastic job of highlighting the pitfalls of an idealistic view of collective resistance and show just how much work is necessary to maintain and rebuild a new world post-revolution. It shows how deceptively easy it is for a collective resistance movement to become the same kind of oppressive quagmire it fought against. Specifically, it shows how much weight is put on individual actors in collective resistance movements. Resistance is struggle. The struggle can be physical or emotional or ideological, but there is always something for individuals in collective resistance movements to have to reckon with. Individual catalysts are good for whipping up a frenzy in the body politic, but true systemic change comes at the hands of the people. Individuals can forget that and lose themselves to the addiction of power or wavering beliefs.

I want to circle back around to Nisi Shawl's Everfair because it is fresh in my  brain and shows how smaller segments of a resistance movement are of utmost importance to it, and how each segment enjoys its own victories and defeats that are small in the context of the larger movement. These small victories, however, are enormous to those smaller segments of resistance. The victories, alongside deep interpersonal relationships and, for some, spirituality, help them to stay the course when the idea of waking up every day and fighting for something both smaller than and larger than their continued survival begins to feel like too much. We could have learned a lesson like this outside of a speculative fiction novel, but it might not have resonated as much.

brain and shows how smaller segments of a resistance movement are of utmost importance to it, and how each segment enjoys its own victories and defeats that are small in the context of the larger movement. These small victories, however, are enormous to those smaller segments of resistance. The victories, alongside deep interpersonal relationships and, for some, spirituality, help them to stay the course when the idea of waking up every day and fighting for something both smaller than and larger than their continued survival begins to feel like too much. We could have learned a lesson like this outside of a speculative fiction novel, but it might not have resonated as much.

adrienne: i find the framework of victory and defeat to be perhaps one of the most problematic aspects of narrative around change. it keeps us from learning. the characters i am interested in are not winning but learning to survive, learning to hold power. i think nnedi okorafor does a beautiful job with this, especially in akata witch, or binti. the characters are up against forces which seek to deny or oppress them, yes, and the strategy is to become more and more themselves, more witch, more different. i think struggle and conflict are key to great storytelling, but only when the author can show us that it is as internal as it is external, if not more so. enemy-based fiction is limited and cultivates the possibility of monolithic simplistic enemies in the real world. stories that explore the complex context and desire of all sides are delicious—legend of korra is a recent example where that was done beautifully. tananarive due's african immortals series also does this in a powerful way—where the drive for power stems from protecting something very precious. how do we keep looking through our projections of ourselves and each other to see what is precious to all?

Bogi: I would not say all stories need a happy ending, or any kind of ending—I agree with Troy that processes of resistance do not necessarily have an endpoint. But when it comes to stories of resistance, I prefer when they end on a note of at least some hope and not utter hopelessness—I personally want to hold onto and reinforce what hope I have, for the struggle tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after. I am biased because they are my spouse, but Rose Lemberg specifically has an amount of stories that show oppression and the fight against oppression very forthrightly and without pulling any punches, but still having hopeful endings—like in their novelette, "The Book of How to Live." I also found in my own writing experience that hopeful outcomes resonate more with my readers.

Sometimes stories can be very open-ended. I think this especially works well when they depict struggles between various factions—which is very true to life: resistance movements are not homogeneous entities unless they are forcefully made so. I just read Wendi Dunlap's "Revival" in the first issue of Fiyah Magazine and that was an excellent example. Some of the characters fighting for survival prefer a closer merging with the alien planet, while some are against, and [spoiler] we do not get to find out who "wins" eventually, or if it is even a "win." And that is perfectly fine.

I very much appreciate when stories examine the aftermath of conflict, too—not only political resistance, but also resistance and/or survival in a more general sense, e.g., the aftermath of war or a natural disaster. As Charles pointed out, stories usually end before that point. Most people do not really look for these issues in video game tie-in novels, but for me, one of the more memorable examples looking at the collective and collaborative aftermath of war, and survival after cataclysmic events, was the Gears of War novel Jacinto's Remnant, by Karen Traviss.

Nino: What might be the limits to the ways in which fiction can nourish and cultivate collective resistance? What might be the dangers or pitfalls inherent in writing, publishing, or pushing for these stories?

Charles: Fiction is a wonderful tool for affirming identities and pushing for change. And it is collective resistance for writers to come together to tell the stories that are important to them, to push back against the dominant narratives that choke the landscape. Who controls the story is always important, though, and it can be a hard thing to face when dominant forces (in publishing and in general) seek to co-opt the stories marginalized people tell in order to further promote inequality, injustice, and hate. To pick a completely random example that could never really happen, a large publishing house could profit both from works about positive collective resistance and works that center the voice of toxic individuals whose life's work has been to undermine justice and progress.

In other words, there is always the danger that by pushing for these stories, we might lose sight of how these stories come to us. If the affirming stories are fed to us by the same hand funneling money and publicity toward those people most responsible for systemic oppression, then that's something we have to recognize. We need to seek to promote justice at every level of production. We have to be aware of where and to whom our money and efforts are going. What we must be wary of is creating a genre of resistance that comforts the dominant without calling for further change and work. The work starts in stories, but without people taking it beyond that, into the streets and the courts, off of the page or screen, the danger exists that it will stall or, worse, become just a new tool to promote complacence and stagnation.

adrienne: yes to what charles said about how stories hopefully do initiate some real-world actions.

something i often feel when people ask about the limitations of visionary fiction (fiction that explicitly challenges aspects of the status quo such as singular heroes and top-down change led by white men) is the assumption that fiction is otherwise neutral. i don't think there is neutral fiction, neutral art. . .there is politically right or conservative fiction, there is work that attempts no politic but upholds the current norms (which, in the societies i traverse, trend away from liberation), and then there is work which offers challenges and solutions to the oppressive aspects of the current norms—sometimes as collective resistance, and more rarely as liberation narratives where the center is truly held and advanced by those who value justice and liberation. in alexis pauline gumb's story 'evidence,' the story is told from a perspective of liberation—i think we need more stories like this, because in centering resistance and struggle we can often end up centering white supremacy, or greed, or patriarchy.

the danger is that we not get so wedded to oppressive constructs, or to ethical rightness, that we limit ourselves or tell boring stories. i love writing black people, and i know blackness is a construct, and i bear the devastating weight of what that construct has allowed to be done to us, to those who share my skin—and i have found comfort and community in that construct! and i don't find comfort in a future in which that construct is ignored or denied! i have to imagine futures in which that construct has been thoroughly fucked with, possibly beyond my recognition because that is, for me, a liberating paradigm. sofia samatar has a story called 'honey bear' in her forthcoming collection tender stories that messed with this for me in a powerful way—asking what is love, family, mothering in a context of true otherness where i both feel blackness in the story and feel something beyond it.

this was one of our biggest challenges for octavia's brood—choosing and cultivating stories that were visionary but also entertaining, interesting, different from each other. some are overt and some more subtle, just like we are in life; some confrontational and some whispering songs of change into the soil.

this was one of our biggest challenges for octavia's brood—choosing and cultivating stories that were visionary but also entertaining, interesting, different from each other. some are overt and some more subtle, just like we are in life; some confrontational and some whispering songs of change into the soil.

Troy: I love what adrienne has said about the impossibility of politically neutral fiction. In SFF we've seen a great backlash to "issue" fiction in recent years. Detractors of political fiction position themselves as wanting to read stories about regular humans in fantastic worlds or situations, as if "regular" in this context doesn't occupy a position of privilege and power.

Authors and the systems that produce, distribute, or gatekeep their fiction are probably the biggest threats to fiction's ability to cultivate and nourish resistance thinking, strategy, and action in real terms. To lean on adrienne again, there is a difference between fiction that seeks to expose or attack oppressive norms, and fiction that dares to imagine worlds where those concepts have been rendered obsolete and something new has replaced them. I'm not saying that the former type of fiction is valueless, but it will always be trendy while oppressive structures remain intact. Authors, then, limit our ability to create a body of fiction that influences a path to resistance, and ultimately liberation if they are not deeply considering how their work should help readers examine—and ultimately develop a vision of replacing—oppressive systems. The constructs that surround authors limit our ability to create a body of resistance and liberation-focused fiction by enabling authors who only play at examining oppression with no real desire or vision for seeing those constructs disbanded. They limit our ability to create this brave fiction by enabling authors who actively practice oppressing others. They limit our ability to consume this brave fiction by championing work that does not challenge readers politically or ideologically. They limit our ability to find the authors who are creating this brave fiction by excluding them and their work from wider distribution or compensation that will allow them to survive and continue creating brave work.

Especially now, we need work that pushes and challenges us to think about resistance and what comes after resistance. The danger is that so many of us are reluctant to expose ourselves to discomfort or struggle on behalf of our message. We begin writing and working to experience some measure of critical acclaim and material comfort, but upending these oppressive systems requires that we deny ourselves and our work comfort in favor of change. We write to the same gatekeepers that exclude our colleagues and grant carte blanche to individuals who have made a business of hatred and oppression. We have bought into the idea that there is a "correct" way to use our words and work to achieve a just society, while those who oppose justice do not share this notion. We oftentimes do not know how to balance exposing our work to the larger body of community—or to neighborhood-level people who could perhaps benefit from it—with maintaining some semblance of material success.

There is no ready fix to these opposing ideas. I started writing about blackness and black people because I carried a legacy of stories inside of me. I also would like to achieve some sort of material success (or at least comfort) from the intellectual labor of creation. However, I also know that if I truly want to dismantle oppressive structures, I need to talk to people who have been historically excluded from necessary work and conversations, while fully realizing that this may kill any ability I have to achieve traditional success. Of course I, and many other writers, are actively redefining what success means for us and our work, but this is still a dangerous paradox that is difficult to reckon with.

Bogi: I'd say one danger is when people, often majority outsiders, use the tools and language of resistance created by marginalized people to perpetuate marginalization. We always need to be on guard against this and point it out when it happens.

I will just bring one particular example, related to the #ownvoices hashtag I also mentioned above. This concept has been extremely useful in finding good representation of various marginalizations, and a shorthand for promoting work—I and many others use it on a daily basis, and I am very grateful that it exists.

But I have seen, especially from white Anglo people in the American publishing industry who want to "promote diversity," a kind of attempt to use #ownvoices to box-in authors—hopefully unintentionally, but I am not always sure. There is often a kind of expectation that if you belong to a marginalized group, you better write an #ownvoices story or else. I am discomforted when I or others are labeled "#ownvoices authors" because I have been advocating for many years to promote marginalized authors writing anything they want. I do not always want to write #ownvoices stories. Sometimes I want to write about octopuses. Sometimes I want to write about totally fictional cultures. And so on. I do not want to always write about my marginalization/s. This was not the original intent of #ownvoices either—it took a bit over a year for this kind of reframing to start to occur. I think this is also related to what adrienne is saying—we can have stories which are both grounded in our identities and reach beyond them.

Carlos: Every fiction, no matter how detailed, creates its world in broad strokes: so broad that, if we think about it too hard, the whole world collapses (see: Derrida). Imagine how many types of green different readers will imagine when you write "the green car," and then multiply that by every act of description, every depiction of a political system, every attempt to create a rounded character a work contains. That's how subject to interpretation the resistance fiction presents is, how many holes readers have to fill in for themselves.

The problem, then, is forgetting this essential aspect of fiction. When a writer becomes popular, the publishing world seeks to capitalize on that popularity by offering more of the same. What resistance requires is exactly the opposite: depth and breadth and ever increasing subtlety, different angles and viewpoints and approaches and conclusions.

The idea that a single "genius" can solve the problems of a society is of course ludicrous when stated in that way. And yet, this is the state of popular art, at least in the United States: sampling and sequels and prequels and remakes and updates. All members of the aforementioned list can, of course, be excellent new art, but it's a list that limits the scope of our imaginings. And limiting imagination—by controlling what artists can produce—is the first step to governmental control. It's an idea as old as Plato's Republic.

Nino: As writers, reviewers, readers, and activists—as well as just people living in anxious, interesting times—what advice can you give for those hoping to foster more collective resistance, both on and off the page/screen? Any other parting thoughts?

adrienne: i think most humans change in the direction of yes, rather than no. that is—when we get scared we often freeze or run away, or fight. and what we need right now is to be so compelled by a future, to feel so much longing, that we move through the fear and trauma and hard times directly ahead of us.

cultivating and encouraging authors who can tell complex visions of the future is important. note that i didn't say utopia. i think we need to relinquish any utopias, especially those that aren't collectively envisioned. that's how we end where we are now—we are trapped inside someone else's utopia, someone who is served by the exact conditions we are experiencing now.

so we need compelling collective futures, we need stories from lots of different kinds of people, we need more collaborative works. we need the work available in more formats—i am too excited about the forthcoming graphic novel of kindred by john jennings and damian duffy.

one more thing—we need reviewers who challenge themselves to receive work that is different because of who is telling the story—and we need diversity in reviewers and editors.

and we need writers to write the stories only they can write—we have amazing models of this right now in tananarive and steven and nalo and nisi and nnedi and sofia and andrea. I am excited by the afrofuturist affair, intelligent mischief's satire work, and of course octavia's brood.

Charles: Troy and adrienne have both touched on what I keep returning to in my head when it comes to steps to take as a writer and reviewer participating in collective resistance. That is, to not only rely on the same systems that have been responsible for and complicit in the oppression of others. There is certainly something to be said for being a part of broken systems and trying to fix them from within. We should constantly be trying to reform systems that don't work for everyone. But we also need wholly new systems. New publications. New blogs. New groups. New movements. New revolutions. There's danger in trying to start from scratch, yes, but also the need to. "The way things are" is insidious. Telling people that they need to work within the system, need to make money a certain way, gain a certain kind of reader, a certain brand of respect, is toxic to real change. Where there are gatekeepers, we need to work to not only go around them but cut them out. In politics and publishing and beyond, there's only so much we can do with systems hobbled by institutional problems. We need to push for and support newness and change, and not to give into financial and social pressures to settle for less than what is just.

To those out there working toward that future, I would say (as I try to say to myself): don't let other people define what success means to you. For change to be successful, success has to be personal. The work has to be (in some ways, at least) its own reward. Take comfort where you can and with whom you can. Strive toward compassion. Be relentless. Don't wait for the revolution to find you—seek it out or start it yourself. Find other people who share your passions. Talk. Share resources. Share love. Do the work.

Bogi: I think one particular mechanism of active oppression is trying to deny us our elders and forebears—to make it seem like everyone engaged in resistance  needs to start from scratch. Joanna Russ talks about this in relation to women in How to Suppress Women's Writing, with many illustrations of how women writers from earlier eras are not only forgotten, but how their work is being actively buried. Not because of its lesser value, but because it comes from a marginalized stance. I have thought a lot about it and I think it is a more general point I see across all my minority groups.

needs to start from scratch. Joanna Russ talks about this in relation to women in How to Suppress Women's Writing, with many illustrations of how women writers from earlier eras are not only forgotten, but how their work is being actively buried. Not because of its lesser value, but because it comes from a marginalized stance. I have thought a lot about it and I think it is a more general point I see across all my minority groups.

I see people come to the diversity in SFF conversation and declare that all older SFF is worthless and was invariably produced by straight white Anglo men. This is not true—but works that fit into the status quo are the ones that get reprinted, promoted, held up as classics, so it is easy to feel there is nothing else. Thus, what I would advise people to do is look for their forebears. To look what work has been done before. In any kind of activism, one is usually not the first, though it might seem so. I have been actively trying to promote this kind of conversation, by starting the #DiverseClassics hashtag and also establishing a Goodreads list for English-language SFF work by marginalized authors pre-2010 and encouraging other people to add to it. I am in the process of planning a reading month related to this effort. It can bring us both solace and knowledge to engage with the work of those who have come before us, and it can also give them hope that they are not forgotten, that their effort continues to bear fruit.

I would just like to reassure everyone: you are not alone. You will not have to fight alone. If we can reach out to each other, and share both our commonalities and differences, there are many, many ways we can collaborate for a better tomorrow.

Carlos: I've seen many Facebook and Twitter posts that wonder what role art can play in a time so oppressive, dire and dark. To those of us consumed by despairing thoughts, I offer this idea: art opens the mind to thought-experiments, hypotheticals, and possibilities. Art simplifies the world to make it more understandable, the same way scientific models help us understand the physical world. Art uses beauty as a tool for communion between disparate minds. Art speaks to the now, but also to the future, where people might be better able to listen. Art is hope instantiated.

In other words, resistance is what art is for. Always. Sometimes that resistance is existential: raising figs to heaven for the outrageous injustice of mortality. Sometimes that resistance is lighthearted, by pointing out the foibles of life in ways that make us smile and nod. And sometimes that resistance is meant to insult the complacency that allows us to make bedfellows of racism, sexism, and all the myriad ways we have of pretending other humans count less than we do. In each case, art provides alternatives, offers camaraderie across space and time, posits the possible against the present moment.

Resistance is what art is for.

Troy: I don't think that I would be remiss in assuming that everyone participating in this roundtable discussion has always lived in interesting, anxious, or dangerous times—though I have to admit that for many of us, things are beginning to look a lot darker. It is our responsibility as writers, thinkers, readers, fans, and activists, to do as Nina Simone says and reflect the times. Through truthful, thoughtful reflection we can make our misgivings with our times and their attendant systems plain for everyone that consumes our work. Our work can help foster the conversations that are necessary for communities to create ways of seeing and being in the world. In a similar way, our advocacy and activism as artists can help to create a sense of connectedness with the larger communities who share our views—and maybe even create some compassion in those communities who don't.

My other advice would be for all of those creative communities listed in the question—writers, readers, and the like—to commit themselves to creating change in a positive direction within their spheres of influence. We need writers to write bravely and envision alternative futures. We need readers to challenge themselves in their reading. We need publishers and editors and reviewers to commit to championing the work of writers who actively oppose oppressive systems through their work and presence. We all need to make a greater effort in engaging with and supporting communities that are not our own. And we all absolutely need to reject hateful ideas and paradigms that have enabled things to go so wrong for so many of us.

Writers, keep writing. People, keep fighting.