Caleb Fox, author of Zadayi Red

Caleb Fox loves what he writes about. His first fantasy novel, Zadayi Red, bursts with the color, life, and beauty of pre-Columbian North America. It draws on the deep reverence for all Creation—including life's rhythms, mortal dangers, consuming passions, powerful magic, and transcendent mysticism—that characterizes his Cherokee heritage. Fox provides a self introduction in the first comment of the interview, which was conducted via email.

Caleb Fox: First, as you clearly know, I write under two names, one of them Caleb Fox, a novice fantasy writer. The other, which I'll keep up to myself for now, is a historical novelist and historian who has published more than twenty books and was an editor for a major New York publisher for a number of years.

Neal Szpatura: You learned of your American Indian heritage as a teenager. How did that happen, and what was the impact?

CF: About the time I graduated from high school, several aunts on my father's side took me into a back bedroom and said bluntly, "We're Indin." (They didn't even say Cherokee.) They showed me pictures of my grandparents and great-grandmother that made it obvious. Then they instructed me strictly, "Don't talk about this to anyone, especially not our men folk. They'll just deny it." End of discussion for many years.

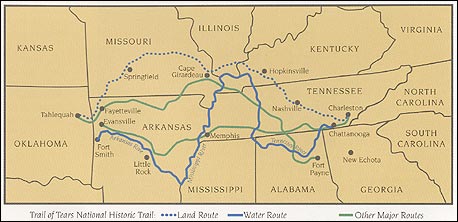

At first I was just tickled, like a kid. Later I began to make inquiries. Found out the family came from around Siloam Springs, Arkansas, and Mountain Home, Arkansas. At the archives in the Cherokee Heritage Center at Tahlequah, OK, I discovered that my relatives migrated west from the village of Nickajack on the Tennessee River, which was known for its bitter opposition to white encroachment. They may have been (though I cannot prove this) descendants of the Tories who joined the Cherokees after the Revolutionary War. In 1829, they accepted an offer of $50.00 to move west along with many other Nickajack Cherokees to "permanent Indian Territory." That's how they ended up among the first Cherokee settlers in Arkansas. Within a few years this same walk became known as the Trail of Tears. At some point, one of my ancestors, probably my great-grandfather, decided that those of us who were sufficiently light-skinned (common among Cherokees then and now) would pass as white. Thus we became rednecks on the east side of the mountain and redskins on the west side.

Cherokee removal routes on the Trail of Tears. Image provided by the National Park Service.

At that point, partly because I was writing historical novels, I began to think about the human side of such a split in a family. It meant that the "whites" could no longer acknowledge their own relatives on the street. Could no longer attend ceremonies that had been part of their lives for at least several generations. Could no longer speak Cherokee in public, and would not teach their children Cherokee. I thought about the relatives I must have in northwest Arkansas and northeast Oklahoma who were raised in a completely different way from the suburban life my brother and I had. When I inquired, I was told that there are tombstones with the family name all over that country. And I began to think of the damage that such a split does to a family: you are no longer my cousin. I won't help you. I won't speak to you. I don't know you. Not that this affected me and my cousins. Our generation simply saw ourselves as white. The older generations bore these burdens.

When I asked the older members of my family, I found out that my mother's grandmother was a full-blood, so red comes down on both sides of my family. But no one wanted to talk about anything to do with "being Indin." We citizens of the twenty-first century can only imagine what it was like. Maybe one day I'll write a story about this kind of family destruction. Or maybe not.

Last: For decades I never spoke publicly about being descended from Cherokees (as well as Welshmen and Irishmen). Though I lived near Indian people and began to walk the red road, the path of the pipe, I regarded my ancestry as my private life. Fifteen years ago Clyde Hall, a Shoshone who has influenced me deeply, said, "Your ancestors are trying to speak through you. You have to go public." So I did.

NS: You are a pipe carrier. What is a pipe carrier? Do you carry for a specific nation or nations? Why did you aspire to that role? What responsibilities does that entail? What was the process of earning your pipe?

CF: The sacred pipe is made of the stem, which is wooden and the gift of the Earth, and the bowl, which is pipestone and made from the blood of the buffalo. Those of us who carry it give it a place of high honor in our lives and handle it in respectful, traditional ways. In it we burn tobacco, which is sacred, and that tobacco becomes our breath (or spirits). As it rises, it carries our prayers to Father Sky.

The way of the pipe is for everyone, and we carry the pipe for all people and all living beings. One traditional prayer with the pipe asks for the welfare of all children, born and unborn, all women, all warriors, all holy men, all sun dancers, and so on.

Through my pipe I find clarity. After I smoke, the agitation of daily life is dispelled. I feel clearer about what I love, what I want to do, what I must do. Responsibilities? Aside from honoring my pipe, I am obliged to share its power with anyone who comes to me in a sincere way and asks to experience its gifts. (This does not mean with the curious or anthropologists.)

I am quiet about my pipe. Though I live in a tiny town of only three hundred people, half Navajo and half Anglo, only four or five know I carry it.

To get the pipe, I got a bowl carved in the Four Winds pattern from Pipestone, MN. I carved the stem myself, and did not decorate it at all, in honor of my model Crazy Horse, who carried a short, plain pipe. Clyde Hall, who knows the ceremony, consented to dedicate my pipe formally in a sweat lodge ceremony.

There's a story here that speaks eloquently about contemporary Indian culture. Clyde is Shoshone-Metis by tribe. He was inspired by Native American activism in the early '70s to go live with the Rosebud Sioux, and lived with the Crow Dog family, the celebrated medicine men, and later was adopted into the Eagle Bear family. And although he is well versed in his own tribe's ceremonies, songs, and rituals, some of his ceremonies are influenced by the Sioux. So I am part Cherokee taught in Sioux-influenced ways by a Shoshone. That's the way Indian country is now. Though the tribes were always very distinct and often enemies, we are developing a pan-Indian culture.

NS: In the acknowledgements for Zadayi Red, you list four people. The first is John G. Neihardt, known to most as the author of Black Elk Speaks, but also a noted poet and teacher. I understand you studied with him?

CF: Neihardt had a huge influence on me. I took a course in the writing of poetry from him and listened to and read his stories of mountain men and Indian people. We disagreed about everything. His verse was Tennysonian, mine modern. He was a mystic, I a rationalist (at that time). Yet I sensed greatness in him and absorbed what I could.

One comment from him changed my writing forever. He made me realize that I wanted to write for everyone in my family, in fact everyone in the whole community, like Mark Twain. I had no desire to be a literary writer, one of those who write for other graduates of MFA programs. This story is told in full on my website.

NS: Another acknowledgement is to Clyde Hall, an authority on Native American culture, but also a gay-lesbian-transgender activist and author. What did your connection with him bring to the book?

CF: Clyde is my chief mentor in the red road and all things Indian. He is not only a practitioner of the traditions but a scholar of them, a profound student of the customs of his own tribe and others. He dedicated my pipe, he taught me to pour the sweat lodge, he sent me on my vision quests, he introduced me to the Naraya dances[1] (which he'd rather I didn't talk about). He is my spiritual fountainhead.

NS: Your third acknowledgement is to Dale Wasserman, the playwright of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest and Man of La Mancha, as well as many screenplays. What were his gifts to your work?

CF: I think Man of La Mancha is one of the truly spectacular creations of the musical theater, probably my favorite musical play of all time. So, after Dale and I became close friends, I was thrilled when he asked me to collaborate with him on a miniseries and then on a screenplay. Doing that process he taught me to write for the screen. We remained friends over the years, and I wish he had lived to see Zadayi Red.

NS: The final acknowledgement is to the Native American leader, Larsen Medicine Horse. Why? What was his influence?

CF: Larsen Medicine Horse is the chief of all sun dance chiefs of the Crow nation. I attended his sun dances, and Larsen arranged the vision quest where we dancers were privileged actually to dance on the Medicine Wheel in the Big Horn Mountains in Wyoming, a sacred site constructed between 300-800 years ago in Wyoming by Plains Indians, where I shed blood with the other seekers by a piercing of the flesh in a traditional, sacred way. He also taught me to conduct a particular Crow sweat lodge ceremony, and for a couple of years I was the leader for the Montana State Indian Club. I owe Clyde and Larsen forever.

By the way, Clyde and Larsen, I've collected a big batch of lava stones for both of your sweat lodges. They come from Mount Taylor, the big volcano that is one of the four sacred mountains of the Navajo. I hope to get up there to give them to you soon—they're too heavy to mail.

NS: Do you personally prefer the appellation Indian, Native American, First Nation person or something else?

CF: I go with the choices of Tim Giago, editor of the former Lakota Times. First choice —tribal name. Second, American Indian. Third, Native American.

The story that Columbus named the indigenous people of this continent "Indian" because he thought he'd sailed to India is an old wives' tale. For one thing, India did not yet exist, and that area was called Hindustan.

The term "Native American" is unfortunate. It originally meant a political movement of the nineteenth century bent on ridding the country of everyone but white Protestants. Several decades ago the Bureau of Indian Affairs revived it as an umbrella term for Indians, Alaska natives, and native people of American territories such as Samoa.

It has never gained street credibility among Indian people, except for those who teach in Native American Studies departments. AIM (the American Indian Movement) opposed it from the start. I avoid it. In Indian country it is the lingo of the outsider[2].

NS: Did you have an "Aha!" moment along the way when you knew you would have to share Indians' stories and spiritual understandings in a new and broader way?

CF: Sure. When I had some bucks that gave me time, I spent a couple of years simply reading everything I could about Western American history. During that time I fell in love—there is no other term—with a man named Tashunke Witko, Crazy Horse. I did not understand my fascination with him. He was a mystic guided by his spirit animal, I was an atheist (or so I thought then). However, I had the good sense to explore this fascination, and it changed my life. Maybe I came to scoff. Certainly I stayed to pray.

Christians shouldn't understand these prayers as being to God. No Native culture I know has a single ruling god. Instead, the prayers are to the powers, whatever powers there are, or to Power itself. This seems to me much more sensible.

NS: The world you have created here is prehistorical in that it's from a time long before writing of any sort in North American Indian cultures. How did you make some of your decisions about what to give the world of Zadayi Red in terms of tools, weapons, culture, etc.?

CF: I wanted to tell a prehistoric story (or stories—Zadayi Red is the first of the Spirit Flight series), because I wanted to be able to dive fully into the mysticism of the culture, including shape-shifting, spirit-journeying, and so on. (I don't like the word magic for these things, because it seems childish. The better word is Power.) At the same time, I wanted to write something to honor my Cherokee ancestors. So I decided to set the stories among the predecessors of the Cherokees.

The difficulty is that the record says very little about these people. For me, that's an advantage and disadvantage. I can't research it and be sure of getting it right, but I'm freer to invent. I learned what I could about the Woodlands period of American prehistory in the country where the Cherokees lived later. Then I used Cherokee customs, traditions, stories, and language—but I had to change them all somewhat. One thing about culture and language—they never stay the same, but always change. Only a few scholars can read the English of the time of Beowulf, which is the equivalent period. Therefore, I based my culture on something authentic, but changed it.

Then I had a great stroke of luck. A new neighbor turned out to be Vincent Wilcox, retired curator of the former Museum of the American Indian Heye Foundation, and later of the Smithsonian. This top Indian archeologist became a dear friend and close advisor. Vince lent me his knowledge about weapons, tools, agriculture, and so on, doubtless saving me from plenty of mistakes.

NS: What is a zadayi? And what's the significance of zadayi red ?

CF: A zadayi is a (fictional) emblem that men in Zadayi Red wear around their necks to indicate success or failure. It's a simple leather disc, painted blue for failure on one side and red for victory on the other. (These are traditional Cherokee associations for those colors.) Secretly, the main woman character, the shaman Sunoya, also wears one, because she's obsessed with knowing whether her life is blessed or cursed.

NS: Zadayi Red is about the tribes of the Galayi, who know themselves as "the people of the caves," although most now live in villages. Can you share some thoughts about the importance of the caves to the Galayi, and to the book?

CF: First, the Cherokee once were called People of the Caves. The cave has been important to human beings for tens of thousands of years. If we weren't living in them, we were making art in them—think of the stunning paintings in Lascaux, Niaux, and other caves near the Pyrenees. (I used this kind of art elaborately in the second book of the series, Shadows in the Cave.) Most important for me, the cave has a huge mythological resonance, a place of the deepest darkness, the unknown, the unfathomable, the terrifying. Mythically, such darkness can lead to the greatest enlightenment. In my book, the route shamans travel from Earth to the world above turns out to be a bottomless lake in a cave. Feels juicy to me.

NS: The ruling structure of the Galayi is interesting, in that "leadership" is divided three ways. Can you talk about that? Did you find historical precedent for that division, or was it a personal inspiration?

CF: Governance by a Peace Chief and War Chief, who kept an eye respectively on internal and external matters, was traditional among the Cherokee. A Medicine Chief offered consultation, and perhaps a tiebreaking vote.

NS: The initial arc of the story is told from the perspective of a young Medicine Woman. Some would say it's pretty gutsy for a man to write from a young woman's perspective, but I know you have some strong feelings about that.

CF: There's an old Sunday School song—

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight

If you insert the word "novelists" for "His," you have a first principle of mine. Fiction brings readers the experiences of all kinds of human beings, and the best way to give a reader the experience of, say, a woman giving birth, is to put the reader inside the mind and body of the woman. Same for letting the reader know how a Palestinian feels about the Jew he sees across the street, or what attitude a Hawaiian has toward the haoles who build high rises on the island's beaches.

Yes, it's hard. You have to do a lot of research, and not just the kind available in print. You have to interview people of cultures you don't know, you have to ask them intimate questions, you have to take time genuinely to listen and understand. Most of all, you have to observe, and minutely. My experience is that, if you approach with a good heart, most people are glad to talk.

A big-name editor once reprimanded me, saying that a white man (which I am not, exactly) cannot write a scene from the point of view of a ten-year-old Indian girl. Idiotic. Fortunately, I think the world is moving beyond this kind of thinking. We must. It is precisely by making the effort to walk in someone else's shoes, to enter someone else's mind and look out through her eyes, that human beings begin to truly understand each other. I believe that goodwill for all sentient beings is the right path for us all, and goodwill comes from understanding.

When I got an award for a book I wrote from the point of view of Crazy Horse, I got a compliment I treasure. The distinguished woman professor who handed it to me said, "After reading this book, I will never look at a person of color the same way again." Thank you.

NS: Zadayi Red begins with Sunoya, a Medicine Chief-in-training, reluctant to disclose a dream to her uncle. Can you say a little about how dreams and dreamwork are important to the Galayi, and perhaps to some Native American peoples? Is dreamwork something you do personally?

CF: There's an important difference between a dream and a vision. Dreams come willy-nilly and are often vague or ephemeral. Visions are sought, usually through drumming, dancing, singing, or a hallucinogen, and they are ultra-clear, like the highest-definition movie on the biggest screen imaginable. Shamanic cultures are generally visionary cultures, and so are my characters here. I have sought and found visions, and they are dazzling. However, vivid as they feel, visions can be hard to understand. They speak in a mythological, symbolic language, not in English. Here's what you won't get from a vision—the Ten Commandments neatly numbered one through ten.

NS: Tsola, the Seer of the Galayi, is a wonderful, beautifully created character. I want all the young women I know to read the book in hope they'll aspire to become her. In addition to the office of Seer, she is the tribe's Wounded Healer. Please describe those two "offices" or paths as you see them and created them.

CF: Tsola is the principal Seer of the tribe. She envisions the future, and she trains the shamans of the various villages by sending them to the world above, where the Immortals live. She heals the tribe by hearing the messages of the Immortals as music and telling the people how the gods require them to act. She is a Wounded Healer because of the sacrifice she has made. By spending years in the absolute darkness of her cave, she has lost the ability to see in daylight. Mythically, many visionaries have been wounded somehow, and are often blind.

NS: Throughout Zadayi Red there are instances of shamanic practice, of experiencing or traveling to what Carlos Castaneda, author of The Teachings of Don Juan, a Yaqui Way of Knowledge, dubbed "non-ordinary reality." Please talk about that.

CF: What can we call it? Alter-reality? It pervades this particular book in the form of the world above. In the next book the underworld is all-important. But these are merely metaphors. Alter-reality exists. Shamanic peoples have always known about it. I have been there, millions of people have been there, and perhaps all human beings have the ability to go. It's real, but not everyday reality. The opportunity to create experiences of Alter-reality and to share them with others who have not accessed them— that was one of the great attractions of writing this book.

NS: Are you yourself trained in shamanic practice? If so, can you/will you talk a bit about your shamanic education and experiences? How did your own spiritual path and your personal experiences of "separate realities" inspire or imbue Zadayi Red?

CF: This is intensely personal, and I'm not going to say much. I have had experiences like this. Some of the visions of Zadayi Red are my own, never mind which ones. Training? My first vision was entirely involuntary, unprepared, and overwhelming. Other visions have opened during drumming, singing, or dancing. You can have a companion, someone to make you feel secure, but I don't know that anyone can be trained. The adventure is yours alone, the understanding yours alone.

NS: You write, "In Sunoya's opinion you could sum up all of Earth's problems in a single word: mortality." And later, ". . . on Earth life was a word of double meaning, because it implied death. . . ." Please say more.

CF: Zadayi Red, which takes the form of an adventure story, is also a meditation on mortality. On Earth there is Time, simultaneously bringing creatures into the world and taking them out, mother and murderer. In other words, there is birth and death. But the beings of the world above are Immortal. Everyone thinks he would like to be immortal. In this book I ask: Is there beauty in mortality? Does mortality make life richer?

NS: One of the most important and interesting characters is Su-Li, a Spirit Guide who commits to work with Sunoya. Please talk about Spirit Guides and their relationship to humans, in the book and perhaps in Native American spirituality, and about your choice of the nature of Su-Li.

CF: Su-Li (the word means "buzzard" in Cherokee) is a key character. An Immortal who despises death, he is punished by being forced to live on Earth and to eat carrion, dead flesh. Nothing could be more repugnant to him. But he develops an affection for a mortal, for Sunoya, the shaman he's sent to guide.

Traditionally, Indian people sought visions to get spirit animals. Crazy Horse's was the red-tailed hawk. Today many people believe they have spirit guides. I have my own. Some psychologists even use spirit guides as patients' therapy. I don't know whether these guides are genuinely outside or are aspects of our inner beings, parts of our consciousness we don't have everyday access to, a kind of higher self. And I don't think it matters.

NS: At one point, Su-Li thinks, "Damned fear. It was the true affliction of the realm between the upper and lower worlds, Earth." How have you had to face fear as a writer, and perhaps even as writer of this book?

CF: Oh, brother. Opposing answers are equally true. My experience as a writer is mostly pleasure. When I roll into the writing every morning, even work that's not creative, an essay or the like, working feels like play. I can barely live without it. My wife won't let me go anywhere without my laptop—no vacations from writing for me. Get irritable if I don't write.

On the other hand, every time I sign a contract to do a book, I am promising to do my best, to give my all, to make heart and soul vulnerable and create beauty. And I never know for sure if I can do it. The thought of letting a publisher and thousands of readers down is ugly. And, yes, scary.

That kind of fear—or any fear—is the true foe of every kind of accomplishment on this planet, and even of joy in life. We all face this question: Which is bigger, the fear of jumping off the high dive, or the fun of it? Having a child, or taking risks that are an inherent part of that? That's the central question of all our lives. My opinion is that daring is everything. When we give in to fear, and all of us sometimes do, we are surrendering to death.

NS: There's a line about Sunoya: "A mother's first duty was to teach her child what it meant to be a Galayi—to understand where you come from, how you arrived on Turtle Island, how to live a proper human life, and how to prepare to pass beyond into the spirit world." [We could put that on T-shirts and pass them around.] Do you hope Zadayi Red may help with those important elements of walking a good road?

CF: Every novel I write, ultimately, is about how to be a bigger, more affirmative human being. [And please put the words on T-shirts and pass them around.]

NS: I like something you wrote on your blog. ". . . I must look at my characters and see how their natures will tilt them into trouble." How does that particularly pertain to Dahzi, the young hero of Zadayi Red?

CF: Oh, Dahzi is an easy one. He has a gigantic calling, to discover how to get a new eagle cape for the tribe. But he's young, and his mind is adolescent. Most of all, he wants revenge on his grandfather, who has been trying intermittently to kill Dahzi for his whole life. So Dahzi gives no heed to his large task, but runs off on a foolish mission of assassination, attacking a well-guarded man who is vastly more skilled in war than Dahzi. We all have our higher and lower selves, or something like that. Dahzi has to go through troubles and then see his way from lower to higher.

NS: At one point, after Dahzi just barely squeaks out of a tight spot of his own creating, his mother and his uncle, both Medicine Chiefs, put him in his place and encourage him at the same time, by saying, "Get a vision. Earn a name. Become a man. Make a life for yourself." But Dahzi also has a bigger quest, a higher destiny. Right?

CF: Get a vision—that reveals the higher destiny.

NS: Do you feel our culture suffers for lack of vision quests and sacred connection?

CF: Don't get me started. Our culture suffers most of all, maybe, because most of us have lost the sense that we are part of a great pattern of life here on Earth, a web that binds us all life into brotherhood. The sense of the sacred, for me, is the awareness of the wondrous vitality of life on this planet—that is the miracle, and we should exult in it every day.

NS: On your blog, you write, "Each character is a universe within . . ." What are some of the ways you find your own way into different characters?

CF: It's hard for a writer, as it's hard for us as human beings, to realize genuinely that everyone is entirely different, a galaxy within himself, strange if not always beautiful. To find characters, I just start writing them in interaction with each other. A family dispute, for instance, is a fine way to discover what role each person plays in the family, what each person likes, secretly covets, and so on. So for me, the way to begin is just to write them. They sort of materialize.

If they're still unclear, or there's something not quite right, I go for a walk with them and ask them what I'm missing, or lie back on the couch and talk things over with them. Sometimes they have surprising answers. One character revealed herself baldly by barking only a single sentence at me—"Get me right!"

NS: Thunderbird, the leader of the spirit realm, says, "Humor is reason gone mad." That's a great line. Any specific illustrations you might care to offer?

CF: Lots of times something profound can be said in a crazy way. For instance, in LA Story, Steve Martin goes back to a blinking freeway sign over and over because the sign has promised to tell him the secret of life. When Martin and his girlfriend solve the puzzle, it's "Sing 'Doo Wah Diddy.'" Wow! Understanding warped into humor. How much better than saying, "Take joy in life."

NS: If reading a good book can be a transformative experience, what kinds of transformation do you hope Zadayi Red may bring?

CF: If any novel seduces a reader into living in another human being's head, into experiences of what another does, into that vivid experience of empathy, it has done something very good.

NS: You write, ". . . according to report, American schools routinely fail to teach kids to love reading. . . If any door must be opened, it is the world of books." If the schools can't or don't do it, then what?

CF: You know things about me I don't remember. The schools apparently are failing to teach kids to love to read. Luckily, parents can do it without trying consciously. Any child who grows up in a household of readers will be a reader, and a thinker. Parents, wake up!

NS: Are there other books that you would recommend to help the country today with awareness, and maybe even understanding, of some Native American culture, traditions and spirituality?

CF: Let's keep it short and simple, so that some readers may attempt it: Black Elk Speaks, Lame Deer, Seeker of Visions, Cheyenne Autumn, Stone Song: A Novel of the Life of Crazy Horse.

NS: On your blog, you say, ". . . cultures reveal themselves most fully and most beautifully in their stories." Can you think of some examples where you have found that to be true, and especially for modern American culture?

CF: The trick is to remember that the culture is revealed in all our stories. Yes, from Toni Morrison to Tony Hillerman to Dean Koontz, to romances, vampire tales, weekly dramatic TV series, sitcoms, jokes told at the corner tavern, and gossip at beauty shops. In these tales are revealed, abundantly if not often beautifully, what we like, what we hate, what we're afraid of, what we're ashamed of, and so on. In the same way every other culture is manifested in its stories—but their loves, hatreds and fears are different from ours. That's why we can learn from stories.

What shows us most beautifully? A short list, and I might change my mind tomorrow, would be Huckleberry Finn, Of Mice and Men, The Old Man and the Sea, A River Runs through It, and (since movies are also stories) Harvey, Duck Soup, It's a Wonderful Life, Field of Dreams, The Wild Bunch, The Deer Hunter, and Victor, Victoria. (I crossed out Cabaret and Love Actually because they're set in other countries).

NS: What are some of your own favorite books?

CF: The books above, the tragedies of Shakespeare, the poetry of Walt Whitman and E. E. Cummings, plus a lot of musical plays.

NS: What are you reading lately?

CF: Carlos Ruiz Zafon, Sue Monk Kidd, Eduardo Galeano, Dean Koontz, and any number of mysteries. I find it hard to read the very distinctive stuff when I'm writing, because excellent writers' styles want to creep into my head.

NS: Any things you always wish an interviewer would ask, but they never do?

CF: Not after all your questions, which were fun, and a challenge.

NS: You wrote, "The object of writing, as of reading, is to sail into the new." What are you working on now, and what's to come?

CF: Right now I'm writing the third book in the Spirit Flight series. After that? It's possible I'll do more fantasy. Riding that wild roller coaster is a lot of fun. But I'm sure I'll do a couple of books about the country I live in, the mix of Anglos, Navajos and Mormons, the mad idiosyncrasies of all these people, the dance played out here daily. The musical score underlying it all will be the incredible landscape of Canyon Country. I love this place and the people who live here. I wish I could call it The Human Comedy.

NS: Thanks so very much, Caleb! Blessings along the way!

Footnotes

[1] According to the web site for the Naraya Cultural Preservation Council, the Naraya "is a tradition of the Great Basin/Plateau peoples that has been revitalized by Native people to perpetuate the healing and renewal of Mother Earth and all her people. The dance is about each of us taking personal responsibility to make this mission of healing and renewal a part of our daily lives. Through the vessel of the dance, we focus our hearts, minds, and prayers on the transformation of our inner beings; based on the premise that we must become in our inner lives what we choose to create in our outer world."

[2] In conversation back and forth about this subject, Caleb Fox provided the following: "Below is a very little work on the term India, quoted from Wikipedia. Note the words 'usually the East Indies.'

In medieval literature and geography: the term "Greater India" (Indyos mayores) was used at least from the mid 15th century. The term, which seems to have been used with variable precision, sometimes meant only the Indian subcontinent; however, at other times, in some accounts of European nautical voyages, "Greater India" (or "India Major") extended from the Malabar (present-day northern Kerala) to India extra Gangem (lit. "India, beyond the Ganges," but usually the East Indies, i.e. present-day Malay Archipelago) and "India Minor," from Malabar to Sind.

"The historic maps of Asia I have call the Indian sub-Continent Hindustan. Apparently the term India came into use in the mid 15th century, but I don't know that it was yet common or dominant. If I knew what language Columbus was writing in (Italian? Spanish? Other?), I could say something better. My guess, and it's only a guess, is that the word might be Indies as easily as India.

"But the point is, really, that 'Native American' has no street cred among Native people, except those who teach in universities. I live among the Navajo and have never heard it from Navajo lips except in front of the media. To them it is a white man term."