Part Two: Crime and Punishment, Law and Disorder

Don't do the crime if you can't do the time. That's the saying, right? So why is it that so many supervillains never quite seem to get around to doing time at all? And why is it that even when they do time, it winds up being strikingly short? You'd think, you kill ten, twenty, a few hundred people, even in a non-death-penalty state, you serve a few hundred years, right? And yet, that really doesn't quite seem to be the case. Crime, punishment, and justice in superhero land somehow don't quite resemble anything out here in the real world, and, it turns out, really can't. Let's take a look at crime, criminals, punishment, and justice in the DC universe and a couple of other places, with a (very) brief stop in the Marvel world as well.

Typically, you've got two general solutions as to how to handle a criminal. First, after long, hard fights, destruction of major chunks of any given city, and so on and so forth, the superhero captures and/or incapacitates the villain! Huzzah! (Though it is worth noting that certain criminals—most typically those done in by Superman and the X-Men, for example—don't really seem to get captured, precisely, so much as disappeared until the next time they're used.) What do you do next? You put them on trial! And here, in the strange backwater of the trial, is where we see one of the sharpest divergences between their world and the real world.

Assume, for the sake of argument, that in the DC and Marvel versions of the United States, the Constitution reads and is generally interpreted exactly the same way as it is here. This means that, almost certainly, no supervillain caught by a superhero would EVER go to trial.

Evidence is key, and the evidence trail may be irretrievably contaminated. The police didn't catch the criminals, they can't necessarily testify that evidence was collected without being touched or tampered with—in fact, if a superhero was involved, they could usually testify that evidence was touched by someone else. What about the methods used to acquire evidence and build the case? Because of their powers or technology, superheroes can collect evidence in ways not available to the regular police—using methods explicitly barred to the police, in fact. It's illegal in all states to record conversations to which one is not a party, for example; exceptions are made for the police only when they go through the process of getting a warrant, laying out their evidence for a judge, and usually only for some fairly large criminal operations. Anyone see Superman getting a warrant to cover stuff he might accidentally pick up through his superhearing? Anyone see Batman getting a warrant for his wiretaps, any time, ever? Spider-Man getting a warrant that allows him to hang on an outside wall and listen to the conversation inside, as he's been known to do a time or two? No? So even if that evidence—assuming there is an actual recording of some sort—gets shared with the police, they probably can't use it for anything, because they can't testify to where it came from or how it was created.

But let's say that the court is willing to ignore the issue of the evidence chain. Then you have to find superheroes to get them to testify. Being generally persons of no fixed abode—or at least no easily accessible residence—superheroes tend to be difficult to subpoena. Difficult, but not impossible. With the Justice League, all you need to do is to find the teleport codes for the satellite—or whatever the current headquarters is now—and zap up there, and somebody will be around to help you.

To be sure, if you can get around to doing it, they will generally comply. Of course, when they do, it can sometimes be a case of "be careful what you wish for." Take, for example, the case of United States v. Carl Sands a.k.a. "Shadow Thief" for the murder of the superhero Firestorm. (We'll ignore the fact that for a simple single murder, a federal court would generally not assume jurisdiction, shall we? Let's shall.) For certain witnesses, things do not precisely go very well.

And that's what happened to Superman, the biggest, bluest, Boy-Scoutiest superhero around. Hawkman, who testified before him and wound up getting questioned about how he's managed to live as long as he has, especially when he seemed to be several different people. There was also the inconvenient matter of him having been arrested a time or two. Can you imagine what would have happened with Batman, who's been known to beat down a criminal or ten to get information out of them? (As far as can be told from the story in Manhunter: Unleashed, he doesn't seem to have responded to his subpoena. Tsk, tsk, Bats. Contempt of federal court is a very serious offense.)

Many, if not most, superheroes have a secret identity; that is, they lie as a matter of daily life about something very, very basic, and in a way that may constitute fraud. For example, "Diana Prince" technically doesn't exist, while Wonder Woman does. "Diana Prince" gets paid by the U.S. government, and thus Wonder Woman, if her secret were known, could technically be accused of obtaining a job under a false identity, for fraudulent purposes. Oddly enough, the same couldn't be said of Peter Parker/Spider-Man, Clark Kent/Superman or Bruce Wayne/Batman, as their civilian identies came first. That said—Civil War and Mephisto nonsense in Spider-Man aside—none of them would ever dream of deliberately revealing their identity on the stand, just to put a prisoner in jail.

Something of a side note: the state of U.S. constitutional law in the Marvel universe must be fascinating to behold. The registration act that produced the Civil War would have an interesting time in our courts. For one thing, requiring people to register because of their actual genes—an inherent characteristic over which they have no real control—would technically rise automatically to a suspect category, forcing the government to fulfill a high threshold for proof that the law was needed. That said, all they would need to do is to point at the destruction in Las Vegas or New York, or the smouldering ruins of Stamford to make their point. Even so, in more normal days, our Supreme Court would probably be terribly divided over enforcing such an act, being on its face a gross violation of civil liberties. (The current real-world Court would, of course, have no such qualms.)

But back to crime and criminals. DC's Identity Crisis proposed an interesting variation: use a mindwipe on them and make them remarkably ineffective criminals—and as long as you're at it, use one on any members of your club who happen to object to make sure they don't remember it, and thus wind up not knowing why people around them start getting murdered, years later.

However, it left a profoundly bad taste in the Justice League's collective mouths when they did it, and wound up eventually leading to some terribly unfortunate events, such as the murders of Jack Drake and Sue Dibny. Catwoman also discovered, in Catwoman #50, that Zatanna had done the same thing to her, to make her a more "moral" person; despite being angry enough to throw Zatanna out a very high window, she nonetheless later asked Zatanna to do the same to some of her enemies, to protect her friends and family.

The alternative to mindwipes seems to be a sort of physical incapacitation—you're still in your head, but there's nothing you can do. In the "Resurrection of Ra's al Ghul" storyline, Batman, of all people, once he'd captured Ra's al Ghul, gave Ra's some really spectacular drugs and shoved him into Arkham under an assumed name, leaving an evil criminal mastermind defenseless and helpless while confined with other insane and terribly powerful criminals, who were looking forward to playing with their new toy. On the upside, it was entirely drug-induced, and left Ra's in complete command of his memory and mind and knowing exactly what was happening to him, if unable to stop it. On the downside . . . it left him in complete command of his memory and mind and knowing exactly what was happening to him, and unable to stop it. That, rather understandably, left a bad taste in the reader's mouth.

But let's say that you the superhero do everything right. Maybe you've been deputized by your city or state, so that you can officially catch at least a few of the bad guys. Maybe the criminal just flat-out confesses, thus removing all need for a trial, or maybe you're someone like Ralph Dibny or Reed Richards, before the two of them lost their minds in their respective universes and before Ralph wound up unfortunately dead: people without a real secret identity, so you can actually testify if needed. And you're not a magician or looking for some highly personal revenge, so the magical or chemical mindwipe option is off the table. The bad guys get packed off to supervillain prison, or the supervillain asylum for the criminally insane, and they're gone and all's right with the world, right? . . . Yeah, right. Because you know and I know that any prison in which a supervillain is held is basically just a building with a revolving door, or an exploding door, or a door with teleporters attached, or a door that gets attacked by a few hundred henchmen, or a door with unexpected helicopters . . . the list is practically endless. The point being, for your average comic book villain, prison is merely a somewhat harsh place to relax, recharge, and come up with new plans for world domination and conquest.

And of course, this happens because really good villains are, in the immortal words of the Joker from the first Batman movie, "all those wonderful toys" for the writer. But put yourself into the mind of the characters—the residents of Gotham City, for example. How would you like to have all those people running amok in your city again and again and again and again and again? It either makes your hero look incompetent, or your city look terrible, or both. Now, the Joker is clearly insane. Whether Gotham is in New York or New Jersey doesn't matter; neither state would execute someone that far gone. (And Grant Morrison's nifty start to All Star Superman #11 notwithstanding, New York doesn't have an active death penalty at the moment.) And as stated, Arkham Asylum for the Criminally Insane and its equivalents are clearly no real solution. Even when criminals don't escape, if they regain their sanity, then they've served their sentence and get released—that happened both with Harley Quinn and the Riddler, both of whom seem, rather improbably, to have actually gone straight these days—and from a human point of view, that really doesn't seem like enough of a penalty for someone who may have killed and maimed dozens, hundreds of people. So, given that execution is off the table, and imprisonment seems unfortunately temporary, how do you solve a problem like the Joker? How do you catch the clown and pin him down? . . . And that brings us to Solution #2.

My, but Nighthawk is very . . . thorough, isn't he? Of course, Marvel's Nighthawk has an advantage that Batman—whose analogue he is clearly meant to be—does not. He's never really pretended to be better than the criminals he stalks. If he thinks you need killin', you'll be dead. Early in Supreme Power: Nighthawk, he in fact kills one person who draws a gun on him, by throwing a tool that pierces the man's jugular; there's so much else going on that the fact that he just killed someone goes almost unnoticed, and besides, the guy would have just died from the poisoned drugs a few minutes later anyway. Nighthawk's relationship with his city's police department is also notably worse than Batman's with the GCPD (which takes some doing) although they're not above using him when they're absolutely forced. He's also an unregenerate racist, of sorts—Kyle Richmond, his alter ego, is a black man who watched white racists kill his parents, so he has a somewhat jaundiced view of most white people—and it works out that minority neighborhoods trust him, whereas they don't trust the police, because he always tries to help them first. (For what it's worth: having torn out the killer clown's middle, then kicked him in the face to break his neck, the clown then falls into the sewer and drowns . . . or more precisely, dies in the water. He's very very very dead. Except, of course, that he fades away and disappears into the water, so maybe, just maybe . . . nah.)

Maxwell Lord had killed the Blue Beetle—shot Ted Kord with his own hand—knew all the secrets of the world's superheroes, had mind-controlled Superman into nearly killing Batman, and would have unleashed him on the rest of the world. Wonder Woman had subdued him and wrapped him in the lasso of truth, so when he said that killing him was the only way to stop him, she knew that there really was no other way. So she did it, one warrior to another, and set off a spectacular set of troubles. Wonder Woman notes in another title that as long as she's running around killing mostly mythological creatures, even when she does it in front of people, everyone's just fine. Killing Medusa? No problem! Killing the Devil—which, granted, most people don't know about, as it sorta kinda happened in another dimension, but there was a really spectacular battle in the Tidal Basin—again, not a huge issue. Killing Maxwell Lord? BIG problem! To be sure, most of the world didn't know about the whole mind-control thing; they just thought she'd killed a federal agent. Wonder Woman eventually gets forced to endure two separate trials, on the "if at first you don't succeed" legal principle (otherwise known as differing jurisdictions, about which more later).

So what do you do with a superhero who feels that killing may be justified? Or worse, fun. To be fair, Oliver—the purple kid—killing the first Mauler clone was kinda sorta almost completely an accident; he just flew through the guy's innards at hypersonic speed, and it turns out that innards plus hypersonics equals mush. The one above, however, was purely for the joy of killing. Invincible himself has killed, accidentally although he was in a towering rage at the time, because Angstrom Levy had threatened his family. Of course, superhero universes being what they are, Levy was only temporarily dead, but Mark doesn't know that yet. But as we see, Oliver killed the second Mauler brother deliberately, no matter what he tells his brother. And yet, everything he says to his brother in the scene below is absolutely true, so, oddly, it's hard to say that he did anything wrong. Or, more precisely, you can say that it was wrong—but at the same time, it's hard to say that he shouldn't have done it. After all, superheroes take the law into their hands every single day. The only reason the streets aren't littered with the corpses of criminals is that the superheroes themselves say, "This far, and no farther."

The problem with refusing to kill the sorts of villains these people run across is exactly the argument that Oliver makes: who does it benefit to refuse to kill if it means that the person you refuse to kill then comes back to murder many other people? It's not even the issue of codified revenge that the death penalty is meant to enforce; it's the simple issue that serial and spree killers will, if allowed to do so, kill again, and kill a lot of people. It's the simple issue that superpowered villains can incidentally and even unintentionally kill dozens, hundreds of people each time they get out of jail. Nighthawk's clown kills four people before he goes to prison, and then, once he escapes and adulterates some drug shipments, more than 3800 drug users. In "Batman: The Man Who Laughs," a reworking of the origin story for the Joker by Ed Brubaker and Doug Mahnke, the Joker kills 15 to 20 people; in "Gotham Central: Unresolved Targets," he adds at least another 10 to 12 people to the tally, through shooting and bombs and whatnot; this includes a period after his arrest, when he gets loose and shoots up Gotham Central police station itself, killing some of the officers. In the noncontinuity "Batman: The Dark Knight" comic, the Joker is said to have killed at least 600 people and . . . I haven't seen anything that would make me doubt that total. Grant Morrison, current writer for Batman and a few other titles, once said that he thought that DC had made a mistake in allowing the Joker to kill. It leaves Batman without any sort of appropriate response, because he does refuse to kill himself; moreover, because DC allowed Batman himself to get so very dark, that winds up being the only real dividing line between Batman and the Joker. No, the Bat doesn't casually torture people . . . but he has been known to beat the truth out of criminals if something important is at stake. There should be more of a difference between your heroes and your villains than the refusal to kill . . . shouldn't there? Isn't there more principle involved than just that?

Every so often, the world decides to hold superheroes accountable for the mayhem that they commit, along with the various supervillains who may or may not be caught. As mentioned, Wonder Woman was put on trial—twice—and acquitted—twice—for the murder of Maxwell Lord. (It's worth noting that her first trial was held at the International Criminal Court, which utterly and absolutely lacks jurisdiction and would not have tried the case in the first place; a simple, single murder is simply not what the ICC is for. The second grand jury proceeding was held in U.S. federal court, and again, given that Lord was killed in Switzerland and technically no U.S. law was violated, the federal court again lacked jurisdiction and should not have started proceedings against her.)

In Ultimates 2 #3, Bruce Banner/The Hulk was tried for the murder of over 800 people in midtown Manhattan; he's sentenced to death and blown up with a nuclear bomb, in a trial that is quite impressively rigged. The trial takes place in midtown Manhattan, possibly within hailing distance of places he destroyed or the homes of people who were killed; Banner doesn't get to appeal the sentence; he's lied to by a "friend," drugged, put into a ship and blowed up real good, all in a matter of hours. Apparently, if you're a metahuman—or at least if you're that metahuman—the risk of him hulking out and making it impossible to carry out the sentence is such that all sorts of U.S. laws have to be violated just to carry out the sentence.

But let's face it: chances are pretty good that if you had a bunch of superheroes and supervillains running around, even the good guys would get a little out of control, think themselves above the law. You'd need to have some way to make them accountable, even if you couldn't realistically put them on trial. You'd need something like The Boys by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson. The Boys find out the truth behind things that happen, and make superheroes pay, if not by entirely legal means. The viewpoint character, Wee Hughie, gets introduced to the need for superhero accountability in a scene that manages to be the sweetest, sickest, and most oddly funny thing that I've ever seen.

Of course, the difficulty winds up being that you can't go after the supers without being one of them; otherwise, you just wind up like Wee Hughie's girlfriend. So he winds up being tricked into taking a superpower-inducing serum, and becoming somewhat super himself.

Perhaps the best intersection of law, order, and superheroes comes in the Top Ten series, by Alan Moore and Gene Ha and others, or in Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Oeming's Powers series. In Top Ten, superheroes—or as they're called in the America's Best Comics universe, science-heroes, although there does seem to be some distinction between those who have native abilities and those whose come from technology or medicine—arose in large numbers in response to World War II in that universe, although many existed prior to that. After the war, most felt they had no place in the regular world, and removed themselves to build the gleaming city of Neopolis, a city that came to serve as a nexus for police departments on many worlds and in many dimensions. Top Ten is essentially a police procedural, pulling together people with (or sometimes without) superpowers, having them investigate crimes committed by other supers, sometimes something as simple as a really disastrous traffic accident (what happens when kids playing tag on strange and wondrous devices pop into your dimension in the middle of a very busy traffic flyway during rush hour? Very Very Bad Things, is what) and sometimes as complicated as trying to investigate what seems to be a drug distribution ring centered within the interdimensional police commission itself. To be sure, if you consider things the way the TV series Law and Order does, then Top Ten is concerned only with the "law" side, police investigation and enforcement. It would be interesting to see how the "order" side of Neopolis works, with trials and jails and whatnot, but so far we've only seen a hint of that, with the jail cells inside the precinct itself. (A side note: the series consists, so far, of five trades, with one more forthcoming either in late 2008 or sometime in 2009: Book 1, Book 2, The Forty-Niners, Beyond the Farthest Precinct, and Smax; the last named is not, strictly speaking, necessary to enjoy the series as a whole, and will in fact make your head hurt just a bit.)

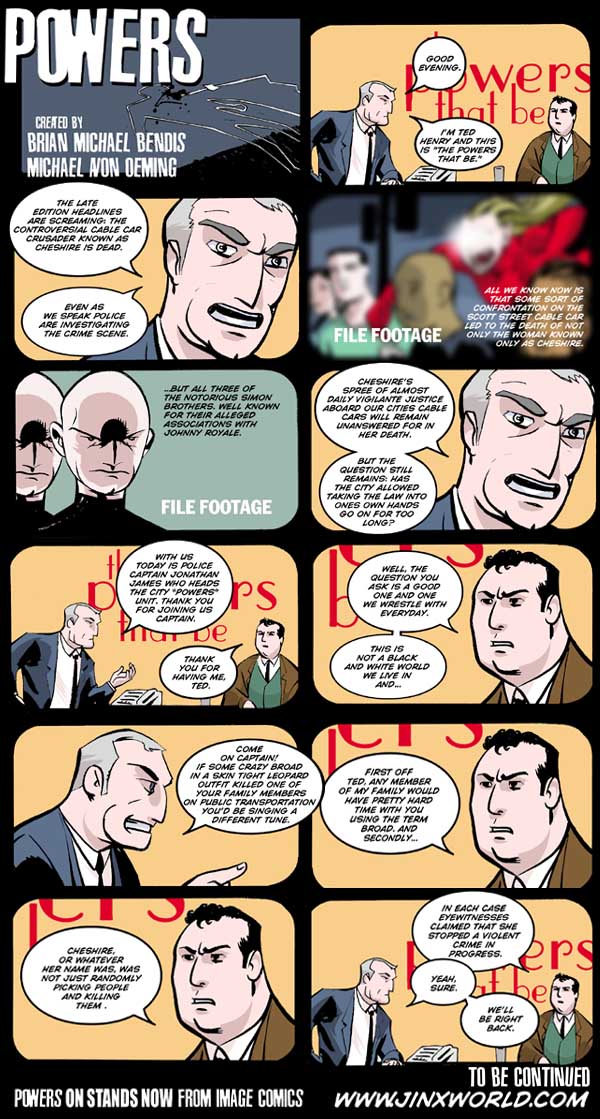

Powers, by contrast, concerns itself with the intersection between law, order, and celebrity and the media, of all things. The core of the story is the relationship between the characters and the procedural aspects, but we also frequently see how the media is covering, and sometimes affecting, a given case. Detective Christian Walker, who turns out to be a former superhero who lost his powers, and Detective Deena Pilgrim, his partner, investigate cases, despite the interference they endure from various people and beings.

(Note: Powers is now published by Marvel/Icon; the above storyline was the original teaser for the series before it changed publishers.) The relationship between Walker and Pilgrim changes drastically over time for various reasons, mostly having to do with the effect of superpowers on their lives. The interesting thing, structurally, is that somehow Powers manages to make the normal people/superhero thing work, in a way that it doesn't quite in other universes. The police are generally forbidden to have superpowers, so they operate more or less like normal police, and the supers, for the most part, respect that. Not the villains, of course, but then, the police can call on the law-abiding(ish) supers to help capture the villains, and they do have technological means of taking away a super's powers so that they can be held once captured. Powers continually asks—and leaves unanswered—the interesting question of just what role the superpowered should play in the administration of justice, how that role should be shaped, and how to hold all the right parties accountable for what they do.

Left to themselves, superheroes tend to just a touch of . . . call it enlightened fascism. They effectively break the laws to enforce them, to ensure the safety of the peoples of their towns and cities. They are enforcing order, frequently against beings or entities far too powerful for ordinary humans to withstand. What makes it bearable is that they're enforcing order usually according to our rules—these activities are crimes and should be stopped, those things are legal and can be ignored, and there's a gray area where, like police, you can use your judgement about how far to take enforcement—and that they usually have one very clearly stated rule of their own: this far, no farther. Superheroes who decide to enforce their own sense of order by their own rules would be too dangerous to be tolerated. There's a reason, after all, that Batman has information about how to take down every single superhero in the DC world. When heroes do kill, if they admit their action, then they get put through the process. Unlike everyone else, they'll wind up in courts that clearly lack jurisdiction, or in courtrooms with seriously rigged trial processes—which, come to think of it, can sometimes be like just about everyone else, can't it?