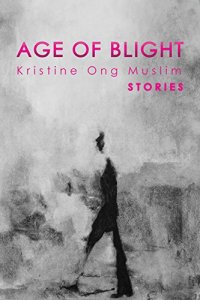

Kristine Ong Muslim’s Age of Blight is a collection of fabulist outbursts for an era of making do with environmental ruin and political despotism. The content, divided into four sections of interweaving very short stories with an introduction, is bleak. The tone is rarely sympathetic to its subjects, though it evokes some pity for the monsters, mutants, and ghosts edging through their tenuous existence. This isn’t to say all the characters are victims, simply that they are all casualties, some more helpless than others.

A long time ago when men were still gullible, it might have been misconstrued as a creature of myth, a creature that was sacred. These days, we all took it for what it was—a creature to quench our appetite to maim other people. ("Pet")

The stories seem to take place outside of time, referencing future events but mentioning details offhand like patent leather Mary Jane shoes ("No More Little Bobos") and telephone books ("Dominic and Dominic") that evoke the recent past, giving the overall feel of the collection something like a set of half-finished Twilight Zone episodes. Muslim, who otherwise displays enormous talent and ideas, sells herself short when she is too on the nose. The central unifying theme between all the stories is the tendency for human beings to be cruel: to themselves, each other, animals, the land, and on scales from intimate to global. But winking lines like, "She said suffering should breed grace, could lead to discipline" ("No More Little Bobos"), and, "I remember reading that the amount of pain we inflict on others shows how much we hate ourselves. Sometimes, it scares me to admit that it might be true," ("Pet") feel a bit too much like Rod Serling’s heavy-browed, viewer-gazing epilogues.

Indeed, the entire section of the book titled "Children" was the weakest to me, since it’s central tension seemed to be the enfant terrible trope on its own. Muslim frequently employs repetition of language to heighten the formal qualities of her fabulism, as well as shorthand and loose characterization. When it works, it evokes incredible wonder and adaptability of meaning. When it doesn’t, it reads like a stiff description of stereotypes.

The other three sections of the book are overall stronger. "Animals" contains what I felt was the best work in the whole collection, "The Ghost of Laika Encounters a Satellite." I had to pause for a cry and a good mull after reading this particular piece. In it, the spirit of the first dog in space reflects on her enduring need to give love, even after being left to a gruesome end by the human beings who exploited her loyalty. Lonely and still orbiting the earth, she tries to befriend a machine by relating these thoughts to it.

Have you seen my collectible stamp? (I had my face on a postage stamp.) I am gazing in the direction of the person who was coaxing me to mug for the camera because I was going to get a steak later. I was looking toward the direction of men. I was looking toward the direction of hope. In one corner, Dr. Gazenko seemed pleased and happy. ("The Ghost of Laika Encounters a Satellite")

Only four pages, the brevity works in its favor and the tension is effective here, as the cruelty it speaks to pushes against the unconditional love of the perspective character, rather than the assumed moral sensibilities of the reader. (To put my own personality in this context, though, I also cried about Rosetta and the Philae Lander, so I’m biased in favor of the pathos inherent to that hostile void beyond our atmosphere.) "Laika" contains a defiant musing in the middle that poetically summarizes the heart of the whole book:

See that? Is she talking about the anger of the discarded, as it is the only thing in the world that is instantly recognizable? No one can look away from it without first being challenged. And that’s my kind of anger, the one felt by the discarded, the type of anger that most people are compelled, for purposes of survival, to ignore. When you look at me long enough, you might catch a glimpse of it. Do you feel challenged? It’s true that we always grow back into our triumphant stable shapes, where we pose as if to contain something, something with a purpose, something with a will to entertain, to love, to hope. ("The Ghost of Laika Encounters a Satellite")

It made me wish more of the stories in this collection had been from these perspectives, these "discarded" individuals and entities. The other two sections, "Instead of Human" and "The Age of Blight," take on tones as varied as zombie slapstick ("Zombie Sister"), body horror ("There’s No Relief As Wondrous As Seeing Yourself Intact"), surrealism ("Pet"), and the pretense of rationality and scientific progress used to justify colonialism and control (the entire "The Age of Blight" section). Individually, all these stories are quite strong. The scenarios are compelling and the language beautiful.

Too often, though, the narrative point of view was that of a bystander or more passive character, and this became noticeable when taken as a collection. I found that I wanted to know more about what was happening from the perspectives of the characters who stood to lose the most, to read from their experiences rather than about them.

By coincidence, I’d been reading Italo Calvino’s collected Cosmicomics shortly before reading Age of Blight, and the two made for an interesting juxtaposition almost as a dualism of fabulist mythologies about the origins and fate of the world. Where Calvino is joyful and whimsical, Muslim is cynical and exacting, and absolutely a match for Calvino in terms of skill and imagination. "Calvino for environmentalist pessimists" might well be a quick elevator pitch to recommend Muslim’s work.

I’m wary, though, of the temptation to use terms like "dystopia" and "post-apocalypse" to categorize Age of Blight. Rather than a warning about an exaggerated, possible future, Muslim is telling her readers about the present. As the Electric Literature review of the book mentioned, "it’s no accident … that Age of Blight comes to us from the Philippines, a nation likely to be one of climate change’s first true casualties."

The anger and despair in Age of Blight most resonated with me in the present tense, though there are many writers (see for example this call from Junot Diaz) seeking to re-invigorate the topical connotations of "dystopia". The speculation in speculative fiction, however, can be its very weakness in this end. As my friend Carrow said to me, it can "relegate real life atrocities and the possibility of resisting them to the realm of the hypothetical and fantastic." How many audiences root for the rebels in the movie theater only to complain about them on the evening news?

Think about the ones who cannot be saved. Think about the ones who cannot adjust to being different. Think about all our stories and those of the ones before us. This terrible unfolding does not always see a blunt object gain shape. Sometimes, it distorts the object and the landscape that conspires to retain its shape. ("Beautiful Curse")

I hope that fellow grouchy science fiction and fantasy readers will find Age of Blight and be similarly reassured, as I was, that they’re not the only ones long past the sense of possibility that accompanies worry, and on to simply coping and adapting (or failing to, and wanting books to relate to just the same). I also hope that works like this will give editors and publishers pause in this post-election nightmare before narrowing their well-meaning vision for the genre to hope and optimism at the expense of other attitudes and endings. As a writer, I worry this will result in artistic respectability politics. As a reader, if Age of Blight left me with any kind of lesson, it is the need to sometimes not resolve, not unify, not balance, and that negative emotions, too, are vital to survival.