Author’s Note: All images are taken from The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya.

Author’s Note: All images are taken from The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya.

I love carpets. As a child, I would make up stories based on the geometric patterns on them whenever I prayed. I might have lost my faith but I have not lost the knowledge that carpets are storytelling tools. Malaysian cartoonist Reimena Yee’s Eisner-nominated The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya brings the storytelling capacity of carpets to the graphic novel. An offshoot of Yee’s larger webcomic, The World in Deeper Inspection, TCMK is the story of Zeynel and Ayşe, seventeenth-century carpet merchants in Istanbul. Volume One recounts their romance. Ayşe inspires Zeynel to leave his scholarly life behind to become a carpet merchant and they marry. Tragedy enters their lives when Zeynel embarks on a business trip to Rumeli. Zeynel has to separate himself from Ayşe after being turned into a ghul—here represented as a vampiric creature—by Mora, an ancient Roman vampire. In Volume Two Mora becomes Zeynel's guest in eighteenth-century London where Zeynel is currently situated as a traveling carpet merchant.

Yee’s graphic novel is multifaceted. At once, it serves as a love letter to carpets and Turkish miniature, a rebuttal to and dissection of Orientalism from the eighteenth century to the present, a lesson on how to tell stories set in cultures and times that are not one’s own, and a reminder that we are always capable of rewriting our own stories.

As Yee’s supplemental guide to the comic makes clear, doing abundant research—and being willing to show this humbling process—is crucial when depicting another culture. Yee’s research pays off, demonstrating that showing your work clarifies your artistic goal, enabling you to better avoid the cliches of tacit and lazy creative ideologies, like Orientalism. Additionally your audience will better understand your approach. They will be able to more readily judge whether your work accurately and humanely presents the culture you are depicting.

Turkish miniature is the most prominent visual inspiration for TCMK. It is an art style that is primarily influenced by Persian miniature (one can read a modern take on Persian miniature in Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis). Miniature in the seventeenth and eighteenth century illuminated texts produced by scholars. While miniature doesn't serve the same function today as it did then, the qualities that determine whether an image is a miniature have not changed. As Neşe Aybey puts it in “The Art of the Turkish Miniature in the 20th Century,” a painting can be considered a miniature if it features “the total absence of optical illusion, three-dimensionality, perspective and light-and-shade, together with the use of pure colours.”

Particularly in Volume One of TCMK, Yee stays true to this definition. When not directly mimicking the flourishes common to carpets, Yee’s borders and backdrops thrive with plant life that could be taken out of any illuminated manuscript before the nineteenth century. The pages wherein Zeynel and Mora are introduced to one another pay homage to the unique approach to time found in many miniature paintings. What Scott McCloud would call scene-to-scene panel transitions are often presented in a single, flowing image in Ottoman miniature as in Mohammed Bey's depiction of the siege of Belgrade. In a similar manner, to show how long Zeynel has been lost—and how far he has wandered from the proscribed route—on his fraught trip to Rumeli, Yee has the flowers in the background shift from Turkish to European. (Here her supplemental guide proves pivotal, as I would not have been aware of the different flowers otherwise.)

TCMK is dripping with cultural detail. Art styles that are similar to or influenced Turkish miniature abound throughout the comic. The author takes inspiration from a miniature in the post-Roman Hiberno-Saxon Codex Aureus of Canterbury when Zeynel exits Istanbul, which meta-textually foreshadows his eventual visit to England. Mora’s backstory is shown to us through artwork reminiscent of Roman mosaic.

Because of this attention to cultural nuances, reading TCMK is an educative experience, and not only because of the inclusion of stories featuring the pedagogic Nasreddin. The reader, for example, is taught how to weave with a traditional Turkish drop spindle. Another, subtler teaching moment comes when Yee illustrates each major praying position when Zeynel performs the morning prayer.

The portrayal of Zeynel’s understanding of Islam is one of the more uplifting aspects of TCMK. Yee frequently includes the text of various surahs (Quranic verses) which, due to his training as a scholar, Zeynel has memorized. She shows respect and care towards Muslim traditions in depicting matters of faith.

Nowhere is this more palpable than when Zeynel prays in the Blue Mosque for guidance from God now that he is a vampire. With tears in his eyes, Zeynel recontextualizes the curse of vampirism into yet another test from God, under the dome of the Blue Mosque.

The dome’s inner wheel decoration is in the center of the page. Stars and the night sky encapsulate the wheel. Zeynel is praying on the upper left and lower right. On my first reading of the comic, I felt moved by the page but could not pinpoint why. It was only on subsequent rereadings that I realized that I was staring at not only a painstakingly flattened representation of the dome’s decoration and calligraphy but a representation of God’s significance to Zeynel. In My Name Is Red, his book about Ottoman miniaturists, Orhan Pamuk frequently echoes the medieval Ottoman view that the miniaturist's flattened, unrealistic style of painting allowed the painter to depict objects based on "their importance in Allah's mind." The dome is flattened, I believe, not only in keeping with the general aesthetic of the comic but because Zeynel is looking directly upwards and we are meant to be looking through his eyes. The stars and the night sky—which many surahs remind us God holds dominion over—that surround the wheel reinforce the notion that Zeynel is praying towards heaven.

It is forbidden to depict God in Islam, but Yee adheres to the tradition of depicting God’s grace through God’s wonders and the works of art inspired by God. After all, as the verse (17:1) from the Quran inscribed on the dome reminds us, God is the All-Seer and the All-Hearer who is known through Signs. I am reminded of Rumi’s poem, “Like this,” specifically the line “When someone mentions the gracefulness / of the night sky, climb up on the roof / and dance and say, / like this.” By representing God in absence except for wonders—both natural and manmade—accredited to God, Yee respectfully shows the mercy and kindness Zeynel finds in his faith.

Yee’s considerate attitude towards Zeynel’s Islam parallels TCMK’s invective examination of Orientalism. As she explains in the supplemental guide, Yee set out to not only showcase the inherently harmful nature of Orientalism but to place it where it was birthed and continues to prosper—the West. Eschewing the type of weak subversion of Orientalism that has not much changed since the “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din,” twist in Kipling’s famous poem, Yee writes:

What gets to me is that in their stories, the agents that they choose to perpetuate the Orientalism are the ‘Orientals’ themselves. Violent, aggressive exotic brown men. Demure, passive, abused women wrapped in fabric. Bucktoothed East Asian uncles tripping over their Rs and Ws. Stereotypes abound. The Other culture is framed as misunderstood, except the misunderstanding arises from the improper perception of the stereotype (hey, guess what, the bucktoothed uncle you saw swindling people is a family man!), and NOT THE EXISTENCE/USE OF THE STEREOTYPES THEMSELVES.

As the story shifts to London in Volume Two, Yee’s art style exhibits a European influence. Unlike in Volume 1, most of the decoration is featured within the panels. Rococo ornamentation replaces the Ottoman-inspired flourishes. One page is based on English manors and features Doric columns. Wainscotting separates the two halves of the page. This European layout is juxtaposed with Zeynel’s Turkish dress, highlighting him as a stranger in a strange land. It is also seared into the reader’s mind that we are inescapably in the West, not just within the context of the narrative but from a strictly artistic standpoint, so that we understand that Orientalism originates from there—lives there—and has little to do with actual Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African cultures.

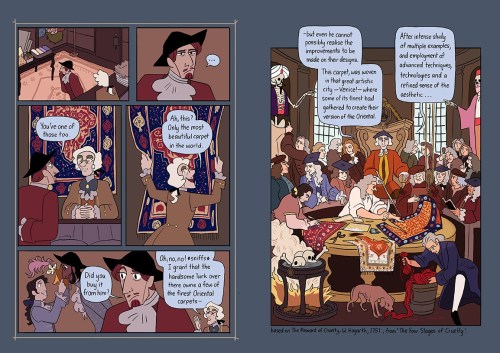

Vampirism as a metaphor for cultural appropriation is Yee’s primary tool against Orientalism. While Zeynel and Mora are the blood-drinkers in TCMK, the monsters in the story are Zeynel’s European clients and acquaintances. In one scene Zeynel and Mora interact with an English carpet merchant. He proudly presents a Venetian carpet to them that he considers an improvement on the Turkish form. Here, Yee makes a direct reference to William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty. On an alluringly disgusting page, Yee links the all-too-common “amelioration” of non-Western art by Western people to the torturous study and sale of literal flesh.

Yee’s lambasting of cultural appropriation reaches its apotheosis on a hauntingly beautiful page that she calls the “grossest” in TCMK. Zeynel and Mora are invited to a Turquerie-themed masquerade by French clients of his who wish to enhance the exotic flavor of their party. At the party, Zeynel and Mora are accosted with a banquet of dehumanization. A recreation of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Une Odalisque is surrounded by vulturesque men. Crimson wine drips from the teeth of one vampiric guest. An individual in a burqa stands behind another dressed as a sultan, with a blood-red feather in their turban. Yee does not let us forget that we are in a European setting with the inclusion of the English manor-style window in the back and the framing of the page with a theater curtain. Our two actual vampires, to the right of the page, are revolted by the cannibalistic masquerade before them. The framing of cultural appropriation as cannibalization would seem heavy handed if it wasn’t for the bleeding Turk’s head pie near the center of the page. Much to my revulsion, Yee points out—in the supplemental guide—that Turk’s head pie is a historical dish which was decorated with a caricature of an Ottoman man.

TCMK would be limited—yet still visceral and memorable—if it was only a beautifully rendered attack on Orientalism. At its heart, in regards to form, it’s a story about storytelling. Numerous inset narratives litter both volumes, a favorite of mine being the shadow puppet show with Turkish puppetry staples Karagöz and Hacivat. These inset narratives are referred back to later in the story. For example, Zeynel and Mora’s relationship is peppered with references to Karagöz and Hacivat.

Both characters, in regards to function, embody one of the comic’s central morals. By using the mutable nature of stories, we are able to recontextualize the understanding of self we gain from others. The repeated motif of the evil eye—in tandem with mirrors—is how Yee explores this moral. Zeynel and Mora both struggle against the expectations placed upon them by their families. Zeynel’s family expects him to become an imam as he is a hafiz (one who has memorized the Quran), following the path of the rest of his intellectual family. Surrounded by figurative branches and under the sharp light of a floating nazar (an amulet meant to ward off the evil eye), Zeynel asks: “Without that ‘hafiz’ title, who am I?” With Ayşe’s help, Zeynel is able to confront his family with his own vision of himself, persevering even though the doubtful eyes of his family members enclose him. Even after Zeynel is turned into a vampire by Mora, he retains his reflection because his sense of self is not dependent wholly on how he is perceived by others.

TCMK posits that allowing one’s understanding of self to be determined by others leads to self-destruction. Mora’s family saw him as a living version of an evil eye and blamed the troubles facing their land on him. Next to the arrow-pierced Roman equivalent of a nazar, Mora recounts how—upon his death—his family refused him proper burial and mourning rites. Accepting their tale of him, Mora returns as a lemure, here reinterpreted as a revenant vampire fuelled by anger. Accordingly, Mora has no reflection.

Zeynel exhibits this same affirmative understanding of self when recounting how he recontextualized the trauma of being a vampire to Mora. He tells Mora that he thought being a vampire meant that he would be undeserving of compassion and mercy, but his faith reminded him that his creator is the All-Compassionate and Ever-Merciful and that, just by existing, he was worthy of those two bounties. This page also marks Mora’s burgeoning self-realization. Yee frames this page within a single-user carpet, tassels and all, revealing why TCMK’s carpet-inspired aesthetic is such an appropriate vehicle for this message of self-actualization.

Scott McCloud, in Understanding Comics, points out that tapestries, a cousin to carpets, are precursors to modern comic books. Though carpets from Muslim cultures tend to omit representations of humans and animals, I would argue that they too are antecedents to modern sequential images. Carpets, Zeynel reminds us in the beginning of Volume Two, are “essentially moving stories.” The static carpet is animated in the viewer’s mind when they make a connection between the geometric figures, ornate designs, and familiar symbols to craft some sort of story for the carpet. In a similar manner, the reader brings life to a comic book by jumping from panel to panel and flipping, or scrolling, from page to page. It might seem entirely coincidental but consider that the form of most comic book pages and panels—oblong rectangles—is also similar to the general shape of single-user carpets. In both carpets and comics, the prevalence of the standing rectangular shape lends to images and designs that are longer than they are wide.

The very foundation of TCMK intersects the storytelling abilities of carpets with comics. While most of the panels in Volume One are rectangular, key panels are modelled off designs common to the niches found in most carpets. These niches are representative of mihrabs—nooks in mosques that are pointed towards the Kabba, the edifice towards which Muslims pray.

In a sense, Yee’s comic can be viewed as one large carpet. The use of parallelism and repeated motifs open to interpretation—red thread, mirrors, and evil eyes, to name a few—are features common to carpets. They are also why carpets are inherently great tools for telling, retelling, and recontextualizing stories.

Though not as openly explored within the comic, the visual spectacle of carpets is enhanced by their tactile nature. Touch affects the stories one derives from them. As any bored child in a mosque knows, one can draw dark or light lines on most carpets depending on which direction you move your finger. In addition to one now being able to add to the art you pray on, rubbing carpets also skews the designs on them, ever-so-slightly changing the geometry and ornamentation and, thus, your perception of them. For an exaggerated example of this effect, see Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed’s warped carpets.

As a result of this wooly distortion, carpets remind us that stories—particularly ones about ourselves—can always be retold and seen from a different view. Yee subtly presents to us the way that touch affects the storytelling potential of carpets when Zeynel teaches Mora to read one. Mora touches and strokes a carpet as Zeynel guides him, similar to how a dutiful father might teach their child to read a comic book. Being taught to read a carpet leads to his finally being able to unsee himself as a cursed being.

Reading The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya reinvigorated my love for carpets as narrative tools. If, like me, you have any fondness for carpets, you’ll love Reimena Yee’s comic. If carpets do not interest you, then read it for its deconstruction of Orientalism or its respectful approach to its characters and their culture. If nothing else, read it because it is undeniably beautiful.