This letter is a knife at my neck, if cutting's what you want. (p. 81)

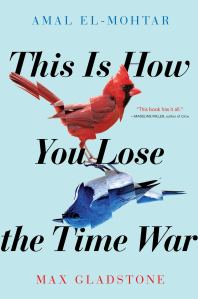

Red and Blue are weapons, elite agents on opposing sides of a multidimensional time-travel conflict between Agency and Garden, rival factions vying for control of the far-future. Sent by their commanders to key points in history across various strands of time, each has become aware of the presence of the other. When both are deployed to the same battlefield, Red feels drawn to seek some trace of Blue, finding a letter marked "burn before reading," which challenges her to respond. She returns fire with her own taunt, and the pair begin to risk everything in a correspondence across time, space, and enemy lines, an exchange of letters that quickly transforms from cheeky goading into a blossoming romantic connection, made tense by the constant physical separation and by the presence of a shadow that appears to be following them both.

Red and Blue are weapons, elite agents on opposing sides of a multidimensional time-travel conflict between Agency and Garden, rival factions vying for control of the far-future. Sent by their commanders to key points in history across various strands of time, each has become aware of the presence of the other. When both are deployed to the same battlefield, Red feels drawn to seek some trace of Blue, finding a letter marked "burn before reading," which challenges her to respond. She returns fire with her own taunt, and the pair begin to risk everything in a correspondence across time, space, and enemy lines, an exchange of letters that quickly transforms from cheeky goading into a blossoming romantic connection, made tense by the constant physical separation and by the presence of a shadow that appears to be following them both.

The correspondence between Red and Blue is developed through a genuine interplay between the writing of Max Gladstone and Amal El-Mohtar, the authors whose collaboration is behind this novella, who write the sections for Red and Blue respectively. The action switches between third-person scenes of each protagonist going about their work, encountering a letter from their counterpart, and reading it, and the letters themselves. In interviews, Gladstone and El-Mohtar say that while they worked to an overall plot structure, the reactions of each character were developed with a genuine element of surprise on receiving each letter, and the scenes accompanying them were written using that emotional response. That feeling of organic reaction and response permeates the text, and the shifts in tone and language from the likes of "Ha-ha, Blueser. Your mission objective's in another castle" (p. 29) to "Sapphire-flamed phoenix, risen, do you command me once again to look upon your works and despair?" (p. 128) underscore and emphasize the progression of the novella's romantic plot, pulling every nuance of its unusual form into service in order to demonstrate the emotional connection between Red and Blue.

The centrality of this connection also deeply affects what we learn about the Time War itself, which is largely incomprehensible beyond its most basic points. The fundamental premise of Red and Blue's war is imparted through language about "strands": there are multiple potential historical paths, which can be influenced to change the future, and strands can also somehow influence each other and be brought into harmony through "braiding," which makes a set of futures more likely and also makes it harder for the opposing side to undo them. The missions conducted by Red and Blue rely on their intuitive understanding of "butterfly effect"-type causalities whose identifications go well beyond us. This poetic obfuscation also stretches to the introduction of the rival factions, and is particularly notable in descriptions of Garden (likely a result of El-Mohtar's more ornate and metaphor-laden style). Take Blue's description of how and where she was born:

Garden goes to seed, blows us away, and we burrow into the braidedness of time and mesh with it. There is no scouring hedge to pass through, we are the hedge, entirely, rosebuds with thorns for petals. The only way to access us is to enter Garden so far down-thread that most of our own agents can't manage it, find the umbilical taproot that links us to Garden, and then navigate it upthread like salmon in a stream. (p. 120)

The information imparted in this passage about accessing Garden's baby operatives becomes pivotal to the novella's climax, but it is also hard to understand much about it beyond the fact that yes, that sounds like something an all-encompassing far-future consciousness called "Garden" would do. Beyond the aesthetic, and the contrast with Red's beginning as a decanted deviant, nothing about the workings of this—the mechanics of the young agents' self-protection or their ability to self-consciously mesh with time itself—is relevant to the story being told here.

The same goes for the objectives and methods of Agency and Garden, which are set up in the more flippant early letters as "viney-hivey elfworld" (p. 27) and "techy-mechy dystopia" (p. 36). Early chapters set up a basic juxtaposition, where Garden likes to do things slowly and carefully and to enhance individualistic potential, while Agency uses its connections between individual nodes to create societal progress, with less emphasis on individual well-being. However, the examples of direct tension are relatively few and there's no attempt to build these up into a coherent picture: Red's victory conditions for her intervention in Atlantis are sketched out, but Blue's interests are more vague, and a pivotal intervention by Garden in the novella's second half remains completely beyond the understanding of the reader. What we are left with are fragments of ideology tied together with natural and technological aesthetics whose glimpses of deeper workings evoke more contrast than opposition (a common motif throughout the novella), and whose only reason for time travel is to secure the conditions that cause them to exist in the future.

That's not to say that there aren't some great, specific worldbuilding moments in This Is How You Lose the Time War. Because this is a novella, things move fast, and every little aside of (usually macabre) description works to set the scene in the most effective possible way, from mobiles of bones in the pilgrim catacombs to the ancient computer shrine that Blue visits in a downstream Agency world; from the vision of the London Underground’s Circle line running long past the destruction of humanity (apparently it’s still a circle in the specific timeline visited) to the eventual glimpses of the worlds of Garden and Agency themselves. This creativity is more than matched in the distinctly non-traditional messaging methods employed by Red and Blue. Reflecting the forbidden nature of their communication, letters between the two are delivered in the aftertaste of seeds and the dance of bees and the rings of a tree cultivated over a century to deliver its message—and, once, a "whacked seal" (because in some contexts, the sealing wax required by nineteenth-century etiquette guides is hard to find!).

The impermanence of the pair's communications serves an important plot point—Agency and Garden wouldn't be believable as all-encompassing forces if their agents weren't using at least some subterfuge to defy them—but it's also emotionally evocative, underscoring the desperate, dangerous nature of the feelings between them and making the constant overtures of trust and increasing honesty all the more compelling. But, like the heroes of our romantic narrative, I've been writing around the most important aspect of this novella without truly knowing how to bring it up. But without burying the lede any further: This Is How You Lose the Time War is an absolute emotional masterpiece, sending readers on a gut-wrenching feelings rollercoaster of the highest calibre.

The epistolary format contributes a great deal towards achieving this, in both explicit and subtle ways. For example, the conventions of letter writing, applied selectively and self-consciously in the early stages, nevertheless allow Red to refer to "My ... Blue" as early as page twelve—it's "My Most Insidious Blue," of course—and Blue reciprocates with "My Perfect Red" by page thirty-five. The first "Yours" on sign-off is from Red on page forty-six, several chapters before the character's more explicit, self-conscious declaration on page eighty-six that "in this letter I am yours. Not Garden's, not the mission's, but yours alone" (after which Blue uses the sign-off for the first time). The path that the romantic connection takes, from taunts between lonely operatives, to curiosity, and then through offering connection and ownership, seeing each other reflected in their (almost always physically separate) worlds, and only then to open declarations of love, feels at once totally natural and painfully uncertain, and the differences in how Red and Blue approach the connection—particularly Red's path from "Ha-ha Blueser" bluster to painful insecurity, and Blue's reflective, analytical approaches, which don't quite prevent her from revealing her inner life once Red starts paying attention—bring personality and light-hearted touches throughout.

While it's the letters that steal the show, emotionally speaking, the glimpses of each character's inner life in the third-person sections are equally well written and underscore the personalities and the changes at play, deepening our connection to them.The near-exclusive linearity of the Agents' correspondence contrasts with the non-linearity of their missions, but it's impossible to imagine the narrative unfolding without that premise. Placing Red and Blue on sequentially equivalent timelines across time and space allows the reciprocal development of their feelings, and it also lets them respond to experiences of time that line up at key points: Red apologizes to Blue for a gap in correspondence after a decade spent with Genghis Khan; Blue's human lifetime spent in one place becomes a mutual source of agonizing separation.

Once again, the fact that the pair can keep track of each other’s non-linear movements is barely explained—and, unlike some of the novella’s other worldbuilding hand-waves, it requires a little more reader buy-in. Neither operative engages in the sort of time travel shenanigans that would be natural in similar stories—turning up to explicitly warn their earlier selves or send messages out of order—because the narrative tension offers no space in which that could work, even if the rules of the world might. And from a structural standpoint, the fact that the exchange of letters plays out linearly means that the incidences of looping causality that do exist—one midway through the novel, and a more significant sequence of events at the climax—become more powerful, given greater weight and foreshadowing within the story, and operating in service to the romance in a deeply satisfying way.

What therefore drives This Is How You Lose the Time War, and what has no doubt driven the outpouring of critical love in response to it (this piece included), is its exquisitely pitched story of romantic connection and its ability to bring all other aspects of the novella—its epistolary form, its expansive and yet understated worldbuilding, its themes of connection and agency and change—into the service of that emotional core. It's a romance whose portrayal of human connection is all the more powerful for the fact that it takes place between two beings who are otherwise not comprehensible to us, leaving their hopes, fears, and longing as the only elements left for a reader to cling to, and thus turning the love between Red and Blue into the most important thing in an unimaginably large multidimensional time war. I don't remember the last time I cried rereading a book, but this one manages it: the combination of raw emotion and desperation as the net closes around the protagonists got me on every revisit to the second half. Reading the authors' descriptions of how the novella came about, it's hard to avoid thinking how much the stars have aligned to give us this book—or, perhaps, how many strands have been braided to bring this story to us, in a form as close to perfection as one could imagine a real book getting.