“Áłk’idáá’” is the first phrase you will ever hear from a Diné (Navajo) storyteller, perhaps as they are surrounded by children while the elders, mothers, and fathers prepare for the ceremony happening that night. “Áłk’idáá’” signifies the beginning of a story with a multitude of possible endings.

“Áłk’idáá’” is the first phrase you will ever hear from a Diné (Navajo) storyteller, perhaps as they are surrounded by children while the elders, mothers, and fathers prepare for the ceremony happening that night. “Áłk’idáá’” signifies the beginning of a story with a multitude of possible endings.

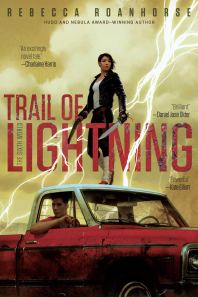

Storytelling is an art as old as human consciousness. It is an activity that often communicated the complexity of a community’s culture to their children, and their children’s children. Stories outline our relationships with all of creation, and convey the internal and external complexity of culture that has existed since time immemorial. For Indigenous Peoples, stories are not simply narratives that one consumes and moves on to the next. Stories are the shared histories and collected memories of people who have seen the world and people who have yet to see the world. Storytelling is an ongoing living tradition, and Rebecca Roanhorse (Ohkay Owingeh /Black/Diné-in-law) has continued that tradition with her publishing debut, Trail of Lightning.

I would describe Trail of Lightning as an amalgamation of science-fiction and fantasy, drawing unique aspects from both genres. Through the novel’s protagonist, Maggie Hoskie, a monster hunter in Dinétah (the name of the ancestral homelands of the Diné), we learn about the world in which Maggie fights to survive. The book begins with Maggie tracking down a monster who has kidnapped a child from the small town of Lukachukai. We learn that Maggie has supernatural gifts, introducing us to what Roanhorse calls clan powers. Not everyone has them, and they are only inherited and determined by the first two out of four clans, a tribute to the kinship system of the Diné.

At first, Maggie may seem like a selfish monster hunter, only interested in getting the job done and the payment, and I would say that you are correct. Maggie is selfish, and as the story continues we learn why. After Maggie beheads a monster, she has no idea what kind it is. It is a creature she has never encountered before and she decides to seek help from Grandpa Tah, an elderly medicine-man, who is one of the few people Maggie respects. Through Grandpa Tah she meets Kai Arviso, a medicine-man-in-training and Tah’s grandson, who appears to know more about the type of monsters that Maggie is up against, and who is encouraged by Grandpa Tah to team up with her. In her interactions with others, Maggie does not pretend to be pure or innocent, especially in a violent world. There is something dark to Maggie that many people can relate to. She has been touched by death, a sort of sickness that can only be healed through the proper ceremonies, which for many non-Diné readers may not make sense, but for the Diné does. And that is the one of the many beauties of Trail of Lightning: the intended audience of this book are Indigenous Peoples, or specifically the Diné.

Within what is currently the United States, Indigenous Peoples represent about one percent of the population. Globally, Indigenous Peoples are between three-percent to five-percent. Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012) defined Indigenous Peoples as “those who have creation stories, not colonization stories, about how we/they came to a particular place – indeed how we/they came to be a place” (Decolonization is not a metaphor, p. 6). That definition gives way to a sense of being, and the relationship that Indigenous Peoples have with the land, which Roanhorse weaves throughout Trail of Lightning through different aspects of Diné ways of knowing. The setting is in Dinétah, the majority of the characters are Diné, and everything else is drawn from the creation stories of the Diné. The entire book is, arguably, Diné.

As a Diné reader, for me this book represents something powerful and something different. There are specific cultural imageries deployed in this novel which only those who are familiar with Diné cosmology will understand and can relate to. But in all of my twenty-plus years of existence, I have never read a book like Trail of Lightning—and that is what makes this book worthy of a reading. It invites and encourages both Diné and non-Diné readers to learn more about the life of Maggie, her relationships with Kai and Grandpa Tah, and her development as a protagonist.

Trail of Lightning does not stop there, though. Within the first 50 pages, it becomes evidently clear that the world Roanhorse has created is not so different from the world we inhabit. Trail of Lightning almost seems like a prediction of a future to come: the world reclaimed by water due to climate change; the existence of a wall that separates Dinétah from the rest of the world, keeping the waters at bay, but also keeping the Diné enclosed; the possibilities of places reclaimed by communities of color, like Aztlán, the ancestral home of the Aztecs, yet also the continuous existence of colonizers, such as the Exalted Mormon Kingdom. The world may seem different, then, but various of its components are drawn from our reality. In all of these possibilities, my favorite aspect of Trail of Lightning is the re-emergence of the Diyin Dine’é, the Holy People, powerful deities unique to Diné cosmology, which are a vital part of the story. As Maggie and Kai continue their journey, they meet several along the way.

It is said that the Diné receive the knowledge for a proper life, and the proper relationship with all of creation, from the Diyin Dine’é. In Trail of Lightning, that same mentality exists, yet Roanhorse does something different. The Diyin Dine’é in Trail of Lightning are different, they are simultaneously familiar and not, making for a paradoxical existence. There is a depth attached to the Diyin Dine’é that I was not expecting, yet appreciate very much. On the individual level, Roanhorse challenges us to be critical of our own descriptions of the Diyin Dine’é. I would never have imagined Neizgháni, one of the twin monsterslayers, born to Changing Women and the Sun as told to me, instead as a distant warrior with a flaming sword who travels by lightning. I had never envisioned Mai’i as a red-velvet-suit-wearing entity with a mahogany walking stick. Such descriptions humanized these immortal entities, who I had previously always thought of as omnipotent manifestations. Trail of Lightning changed that, which is another beautiful aspect of its story.

The important aspect of stories is that they are living breathing entities. They are not static; they are dynamic. They grow and change just as humans grow and change, and reflect the changes of the world. All of which contributes to the collective memories of a community. Stories, then, are not simply just vehicles for entertainment. Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, a Lumbee scholar and theorist, argued that “stories are not separate from theory; they make up theory and are, therefore, real and legitimate sources of data and ways of being” (Toward a tribal critical race theory in education, 2006, p. 430). Brayboy argues that stories orient people to what it means to be. For the Diné, our stories inform us how to be Diné. Stories serve as community lessons, detailing and outlining our responsibilities to each other and to the world.

Stories reflect the people who tell them, who share them, and who invoke them. In Trail of Lightning, Rebecca Roanhorse, an Ohkay Owingeh, Black, and Diné-in-law woman, shares stories from another world with this one. She gives us a gift fashioned by the gifts of others, and offers something different and powerful. Trail of Lightning reflects Roanhorse’s own archive of memories and ways of knowing. It is clear that Trail of Lightning descends from a historical and living tradition of storytelling, and the novel reminds us of that. Although “áłk’idáá’” is not the first word you will read in Trail of Lightning, it is for me the paramount word to explain the significance of storytelling in the twenty-first century by Indigenous Peoples for Indigenous Peoples.