Mame Diene, photographed by Geoff Ryman

I am on a flight from Nairobi to JFK. The technical issue has been identified, and we’re finally about to take off. It’s a fifteen-hour flight so, praise be.

The delay wasn’t particularly long, and I had time to breeze through an interview of Tade Thompson in The Guardian. For those of you yet unfamiliar with Tade Thompson, here you have, in many ways, the flag-bearer for African science fiction and fantasy. His ongoing Wormwood trilogy, about an alien invasion in Nigeria, properly decolonizes science fiction by taking a stab at colonization and its hypocritical benevolence; changes its cultural and geographic setting and takes on a heretofore unseen approach to the classic (and often colonial) tropes of alien invasions.

I will not say more, and will allow you the pleasure of discovering Tade’s work firsthand. It is well worth your read, and with enough short stories for a couple of collections, you can find plenty of his work online and for free. You have zero excuses.

Social media algorithms are such that the next article suggested was on Nnedi Okorafor’s criticism of the World Fantasy Award’s prize in the form of H.P. Lovecraft’s bust. Here too, a slow but gradual effort to address our historical, cultural, and literary failings, and recognizing that the genius that one manifests in words might be anathema to the values the author embodies in life. An appreciation of art doesn’t require a cult of personality.

If Tade is the flag-bearer of African science fiction, many of our cultures are matriarchal, and Nnedi is, in more ways than one, the mother of the speculative nation we are building every day. A nation of African speculative fiction beyond the borders drawn arbitrarily across the continent.

Nnedi just won the African Speculative Fiction Society’s annual Nommo Award for her work on Shuri, a Black Panther spinoff about T’Challa’s genius sister. Spinoff today, hopefully standalone tomorrow. Nnedi generously donated the prize money back to the African Speculative Fiction Society. Nnedi’s own novella trilogy Binti has been nominated and received several awards for a breathtakingly innovative approach to the challenges of identity and coming of age when the world and worlds around you demand that you give up who you are.

Non-English speakers can now appreciate both Nnedi and Tade’s work in several languages: French, Spanish, and even German. If there was ever a time for African speculative fiction it is now. Before it gets appropriated by the industry and mainstreamed to death, African speculative authors need to produce more, be bolder and more creative, and achieve the seemingly impossible: be accepted for their art without their skin color or origins weighing on their visibility, respectability, and credibility as authors.

Tade just won the Prix Julia-Verlanger (Julia-Verlanger award) in France. This is a somewhat singular achievement and something as Africans and African writers we can all be proud of and aspire to. Isn’t it?

It is.

And yet, despite nigh universal access to what are sure to become classics of African speculative fiction by readers outside the Anglosphere, translated works of African speculative fiction from English into other languages also contribute to impoverishing the genre.

My comment is not about Tade or Nnedi. It is not a comment on their skills as authors. It is not a comment on whether or not this universal acclaim is deserved. It absolutely is.

Rather, to position this piece in the Coppolesque, dare I say Scorsesian, debate over the value of Marvel movies, translating popular novels and novellas by African authors from English into local languages becomes a barrier for authors writing in languages other than English.

Rather than reach out to francophone, lusophone, or German-speaking authors on the continent and in the diaspora, French, Spanish, and German publishers take the easier route of waiting for an author to be successful, translating them into their language, publishing them on the national market, and guaranteeing themselves a return on what is a relatively risk-free gamble.

It is lazy publishing.

While French readers will be reading The Murders of Molly Southbourne in French over a glass of Saint Estephe by the hearth this Christmas, they will not read francophone African authors. They won’t even know they exist.

This might be construed as the rantings of a frustrated author who writes in French as well as English, who should instead work on his craft rather than draft some derivative article hoping to bank on Nnedi and Tade’s success and get published somewhere and championed by haters.

This might be construed as the rantings of a frustrated author who writes in French as well as English, who should instead work on his craft rather than draft some derivative article hoping to bank on Nnedi and Tade’s success and get published somewhere and championed by haters.

Perhaps I should, but there is no ethical consumption under capitalism, and that’s my point.

I get it. Publishing isn’t the most bankable of endeavors, publishing in the genres even less so, and publishing in the genres outside of western markets the epitome of masochistic wordsmithing.

If one has to make ends meet in an already impossible market, one is less likely to take risks, and translating, repackaging, and marketing success seems like the most logical thing in the world. One might even convince oneself that by doing that they are bringing a spotlight to the genre, which will in time allow for local authors, the French-speaking, the Portuguese-speaking, and the German-speaking, to find a place for themselves.

It won’t.

Rather, just like the MCU it creates a lucrative reality that doesn’t incentivize risk-taking, that doesn’t eventually make way for a utopian twist. It is market capitalism, and when has THAT ever worked for the little guy? For the young woman in Kisangani trying to promote her novel online, getting rejected by established publishers? The very few publishers of genres in her language because they’re too busy debating what Binti’s French cover should look like? Because they have already ticked the African/Diversity checkbox on this year’s targets, but will, oh absolutely will, dig her manuscript out of the slush pile next year?

They won’t.

Believe me, at the Stephen King-like velocity with which Nnedi and Tade seem to mass produce brilliance, the non-anglo publishing sphere will have bankable translations galore for years. And given that anglophone, especially American, publishers seem to be more willing to invest in African novels, take risks, and give seven-figure advances to unknown writers, there will be plenty of Tades and Nnedis to pick from.

The only way to buck the trend is for non-anglo publishers to make a conscientious effort, and make space available for new writers to emerge.

Perhaps for every African speculative fiction novel translated into whatever language, the publisher could publish another African author in their own language.

Perhaps as non-anglo readers we can, for every translated novel we purchase, try and purchase something by a lesser known author in our own language.

We all have a part to play here. Readers, writers, and publishers.

As writers we take risks with our art every day. Readers and publishers, we just ask that you do the same. Unless complacency is the name of this game. Or worse yet, its nature.

Non-anglo editors and publishers, thank you immensely for the work you have done for the last century, publishing local authors in their own languages. There wouldn’t be an Italian, French, Polish, or Japanese science fiction and fantasy scene without you.

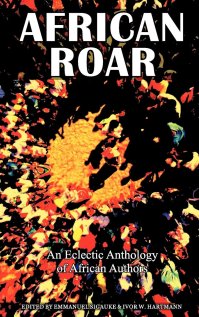

But remember that if publishers like Ivor Hartmann and Emmanuel Sigauke hadn’t started African Roar years ago, you wouldn’t have three volumes of AfroSF today and a murder of authors to pick and choose from and translate. StoryTime, Omenana, and the late Walter Dinjo's Subsaharan Magazine all took a risk working with inexperienced authors without any guarantee that they would find a response with the public.

But remember that if publishers like Ivor Hartmann and Emmanuel Sigauke hadn’t started African Roar years ago, you wouldn’t have three volumes of AfroSF today and a murder of authors to pick and choose from and translate. StoryTime, Omenana, and the late Walter Dinjo's Subsaharan Magazine all took a risk working with inexperienced authors without any guarantee that they would find a response with the public.

Why can’t you?

While your job is also to make the inaccessible accessible, and celebrate the diversity of human creativity, remember to celebrate your own. We are myriad drumming at our keyboards, our smartphones, scratching with a pen by candlelight in a power cut.

Beats echoing each other in the darkness. Rumbles and roars.

Most of us won’t ever be as big as Nnedi or Tade. Most of us won’t make it past sharing our little moments of pride with our intimate circle of friends. But one or two of us might shine, shine bright, and that is worth all the translations in the world.

P.S.: Don’t translate this article.