Every six months or so, I think about ghosts. It’s rarely motivated by anything, but it’s weirdly consistent. It usually goes like this: I’ll find my thoughts returning to a space. A house, a city, a community. I’ll end up wrapping that space in thoughts of its history and people, its simmering resentments and riotous joys. I try to understand it simultaneously through the lens of political economy and personal narrative. Eventually, I return to one of a few pieces of media. The filmography of Wes Craven, the four Pulse movies, the weird fiction of William Hope Hodgson and M. R. James. David Lynch’s work as a whole, but especially Twin Peaks and the television it has influenced.

Every six months or so, I think about ghosts. It’s rarely motivated by anything, but it’s weirdly consistent. It usually goes like this: I’ll find my thoughts returning to a space. A house, a city, a community. I’ll end up wrapping that space in thoughts of its history and people, its simmering resentments and riotous joys. I try to understand it simultaneously through the lens of political economy and personal narrative. Eventually, I return to one of a few pieces of media. The filmography of Wes Craven, the four Pulse movies, the weird fiction of William Hope Hodgson and M. R. James. David Lynch’s work as a whole, but especially Twin Peaks and the television it has influenced.

I’m in the middle of rewatching Scooby Doo: Mystery Incorporated right now. Scooby Doo as a whole is a pretty brilliant exploration of a materialism of ghosts. Not just because there are functionally no supernatural elements—the haunting is always some incidental character in a costume—but because over the show’s half-century of various series, it consistently provides those hauntings with a political-economic basis. An old man haunts an amusement park in order to drive a rival out of business; a woman haunts a gas station because shipments failed to be delivered; children haunt a neighborhood to gain autonomy from their parents.

The hook of Mystery Incorporated is that it serialized the show, allowing space for character development and a broader mystery that had previously been avoided. It also directly referenced authors like H. P. Lovecraft and Harlan Ellison (who played himself), and shows like Twin Peaks. It is a more or less explicit Weirding of Scooby Doo, and it’s endlessly fascinating for being what it is. In part because what we mean—or at least what I mean—by Weird is often precisely what I think Scooby Doo has always done: develop a materialism of ghosts.

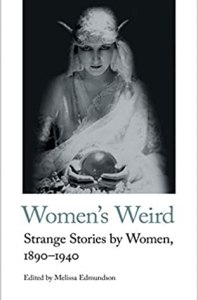

I suspect my definition differs slightly from the one operative in Melissa Edmundson’s Women’s Weird: Strange Stories by Women, 1890-1940. Edmundson’s introduction includes a number of definitions, from Lovecraft’s “breathless and unexplainable dread” to Eleanor Scott’s invocation of the “borderland between the world of dreams and the world of everyday” to Mary Butts’s definition of the supernatural as including “theories of life existing beyond, or generally beyond our perception.” In the same section, she quotes James Machin as saying that defining the Weird “is intrinsically problematic for critical discourse.” It’s the position that Edmundson seems most fully to share; the stories collected in the book certainly don’t all abide by Lovecraft, Scott, or Butts’s taxonomies, in a way that is mostly a strength.

The collection itself is a bit strange (no pun intended). The introduction by Edmundson reads more like a thesis defense (or a book pitch) than an introduction to these authors and their work, and I couldn’t help but feel like it would have helped the flow of reading Women’s Weird if it had had a more forceful or polemical introduction and moved what is currently there to the afterword. Instead, it sets itself up as a bid for a slight shift in the existing academic canon, which feels tepid. Especially when considering the quality of some of the stories collected.

To the meat of the matter: there are some genuinely excellent stories collected in Women’s Weird, and a greater proportion of those than there are of duds (there are some real duds, though). Literature has a capacity to haunt—to pop up unbidden in impossible places in the brain, to radically recontextualize a space, to become an embodiment of history—and the best stories here do just that.

Edith Nesbit’s “The Shadow” is arguably the standout. It is a tale of a terrifying shadow that appears in the corner of the eyes of two friends, one in love with the other who is married to a mutual third. Nesbit’s writing is playfully detail-oriented, but the story is especially elevated by the way it frames itself. It begins:

This is not an artistically rounded off ghost story, and nothing is explained in it, and there seems to be no reason why any of it should have happened. But that is no reason why it should not be told. (p. 55)

Read as a piece of the story it is apt; it works even better as a critical primer.

The thing that makes “The Shadow” so unusual is that it is a haunted house story about a brand new building. The history that ghosts often operate according to is jettisoned. Or, at least, inverted. Instead of an old house being a façade for some sort of ancient crime of passion brought to bear, the interpersonal anguish is metaphorized into being. If we are used to haunted houses as tools to (narratively) explore a past traumatic incident, then Nesbit is asking what it looks like to be actively engaged in that traumatic, inexplicable moment.

May Sinclair’s “Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched” functions similarly as both a compelling narrative and immanent critique, although, in its case, it is specifically well paired with No Exit, Sartre’s “Hell is other people” play. Sinclair tells the story of a woman through her love affairs, and then her own death. Hell is, for her, another person; a man she had an affair with for some time that devolved into boredom and spite. Her final reward is to be trapped in that boredom and spite with him for eternity.

In the introduction, Edmundson points out a double bind: women are assumed to only write about domestic themes, and domestic themes are supposed inferior to more universal concerns. For Sinclair hell isn’t the fact of other people. It is the specificity of domestic relations, how they are stigmatized and fetishized, and how those social pressures disallow people from acting on (or even properly recognizing) desire (for others or in terms of what they want for themselves) until they are already in retrospect. It’s a strong literary argument for the universality of domestic themes.

The collection’s (arguably) two most famous authors provide the most elliptical and haunting—in the “it is sure to stick with you” sense—stories. A number of the collected stories deal with the purchase of real estate, but Edith Wharton’s “Kerfoil” turns it into the central image around which history can be revealed. A prospective buyer visits a property only to be followed around by a wary pack of dogs. He then returns to town to get the story of the previous tenants, which include a vengeful husband who jealously wrings the necks of his wife’s pets. It is propriety and the property relations of late nineteenth-century England itself haunting these people, in much the same way as grief or a sudden, violent end does in other supernatural stories.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Giant Wisteria” is arguably the most conventional ghost story of the collection. She opens with a frame narrative in the past (signified by dialogue like “Aye! Thinkest thou I would cast shame into another man’s house, unknowing it?”) before jumping forward to a group of teens who discover what came of that moment. The story itself feels like it should have already been adapted to film a couple times over, with perhaps a recent prestige television series. The campfire style in which it is written couples with the frame narrative to produce something compulsively readable with just enough of an edge to stick in the back of the brain.

There are other standouts as well. A sort of loose trilogy of haunted household items is formed in Louisa Baldwin’s “The Weird of the Walfords,” about a cursed old bed, Margery Lawrence’s “The Haunted Saucepan,” which is about as perfect a title for the story as could be hoped for, and Mary Butts’s “With and Without Buttons,” about some gloves and the way that fictions can stumble upon and reinforce historical facts. The less interesting stories, whether because of their language or their failure to develop theme or character in as compelling ways, don’t drag these down. But they are instructive in their own ways.

Francis Stevens’s “Unseen—Unfeared,” for instance, reads in many ways like an attempt at an anti-racist response to Lovecraft’s most notorious story, “The Horror at Red Hook.” Edmundson even positions it that way. It is, unfortunately, full of none of the compelling imagery or hyperspecific language that pulls a reader into Lovecraft’s writing. And it’s also not a particularly compelling anti-racist message. As Edmundson puts it, Stevens “presents racist thoughts as a sickness, the thoughts of one who is deranged in mind, not a part of normal human feeling.” Aside from the ableist pathologizing there—which is also one of the criticisms of Lovecraft’s own work I would like to see more thoroughly examined—it is an individualist fantasy no more useful for understanding the systemic reality of racism than seeing a car with a COEXIST bumper sticker. Scooby Doo’s farmers who dress up like ghosts to steal some arable land have infinitely more to say about race relations.

Eleanor Mordaunt’s “Hodge” similarly overreaches without simultaneously overdelivering. The story is of two siblings who find a frozen man who is probably the fabled Missing Link in a forest that they had previously only dreamed. The story then more or less abandons the supernatural element to double down on how this old guy is horny and the brother has to protect the sister from that, which ended up striking me as unfortunately gendered.

Mary Cholmondeley’s “Let Loose” doesn’t merit an ideological critique so much as a literary one. Like Perkins Gilman’s story, it opens with a frame narrative, except in this case it is totally ancillary, suspenseless, and awkwardly written. And like Wharton it hinges around a question of dogs, but instead of blossoming out, it withers into a dull reveal. Eleanor Scott’s “The Twelve Apostles” is similarly overwrought, although its detective airs and tentacled monstrosity, at least, place that more firmly in the Lovecraftian context. Which is as good a place as any to be overwrought.

None of which is, to my mind at least, a reason to avoid the book as a whole. At least not when so much else here does work so well. Scooby Doo is certainly no stranger to awful writing, outdated racial and gendered thinking, and worse. It’s also not explicitly aiming to reconfigure a canon that desperately needs reconfiguring, though.

The reason I wish Women’s Weird was argued and laid out differently comes down to those weaker stories. There is, I think, a strong argument to be made for exactly this collection. But it is one that needs not just the full conviction of an academic realignment but a clarity of purpose beyond that. I wish the case was made here, for instance, for a clear-eyed look at the failures of the Weird beyond an advocacy for gender diversity in the face of racism. The presumption, I assume, is that this is the purpose of an academic realignment. That these arguments (or whatever the editor’s version of them is) need not be made in the text itself, because context and polemic are what inclusion in an academic setting allows. Bring the stories to the classroom, and the teacher and students will draw out their quality, their ideological shortcomings, their context.

It is clear the book does not believe that the stories speak solely for themselves. The introduction would not be here if that was the case. And as much as I enjoy many of these stories, I think that is the right impulse. The state of Weird fiction has been an active battleground for more than a decade at this point, with perhaps the most famous flashpoint being Nnedi Okorafor’s call to discussion around Lovecraft’s likeness being used for the World Fantasy Award. After winning one herself in 2011, Okorafor was able to start a public discussion about Lovecraft’s racism that had been privately percolating for decades. In 2016 the design of the physical award was changed, the bust of Lovecraft discarded.

Direct interventions like Okorafor’s can be bolstered by the kind of work that Edmundson has produced here and the kind of work that I try to do where I can. Recontextualizing historical work into the Weird, whether it’s Charlotte Perkins Gilman or Scooby Doo, allows new purchase to the affects that the genre (or mode) is associated with (a dream-like, cosmic terror) and the exegetical models it sustains (whether that’s a materialism of ghosts or a recontextualization of the naturalized “fear of the Other” into structural race analysis). That, in turn, gives readers the ability to emotionally process and pinpoint these feelings and arguments inside of new contexts. It can teach us new ways to be haunted or old ways for others that we might not have been aware of—by domesticity and affairs and brand new houses.

If I come down harshly on Women’s Weird, it is because I think that it could have done much more to facilitate that ability. As a collection of short stories, I think it’s a really very pleasant diversion. Especially when read over a few weeks and paired with two seasons of Scooby Doo: Mystery Incorporated. Both are likely to haunt you longer than you might expect.