It is now a long established tradition at Strange Horizons that the Reviews Department begins each new year by reviewing the one just passed. In three parts this week, our reviewers carry on this ritual in fine style. Certain themes and works recur with regularity, but one of the things that struck us this year is how ambivalent these pieces, taken together but also within themselves, prove to be: 2022 was, depending on which of our reviewers you ask (and perhaps even at what time of day you ask them), a terrible year or a rather good one; replete with challenges or full of hope for a future. Like most years but more so, it was perhaps all these things at the same time: a year in which the struggles we all face became almost painfully clear, but in which we worked together more than ever to try—at least try—to meet them. Science fiction and fantasy is at the forefront of how we imagine our options; the year in genre was, possibly unsurprisingly then, unusually fertile.

This rude health—and our reviewers’ remarkable alertness to it—was a huge comfort during a year which will forever, indelibly, and overwhelmingly be marked for the Reviews Department by the loss of our Senior Editor, the redoubtable Maureen Kincaid Speller. In her introduction to last year’s In Review piece, Maureen wrote, “I’m writing this with no clear idea of what the new year is about to bring us, other than […] be kind to one another wherever possible.” As ever, we will in 2023 do our best to follow where she led.

Catherine Baker

You know what they say: you wait all year for a one-of-a-kind language-based magic system flexing its critiques of technology, capital, and power, then three come along at once. My book of the year was R. F. Kuang’s Babel, which doused the colonial and orientalist structures of academic knowledge production with strong measures of translation theory and anti-colonial global history, then burned the whole edifice down. Meanwhile, Scotto Moore’s Battle of the Linguist Mages uploaded postmodern occultism to the age of competitive disco-MMORPG gaming, as a champion streamer wrested the arcane knowledge of “power morphemes” from corporate and extradimensional baddies; and Robert J. Bennett closed out his Founders Trilogy with Locklands, projecting his sigil-driven art of “scriving” into a networked cyberpunk near-future that becomes all the more pointed through its alt-Venetian setting. Meanwhile, Tamsyn Muir’s Nona the Ninth came as an unexpected addition to the Locked Tomb trilogy (now surely deserving the strapline Disaster Lesbian Necromancers in Space), and I caught up belatedly with Shola von Reinhold’s slipstreamy art-historical mystery LOTE, in which a queer Black British artist fascinated with the Bright Young Things pieces together the history of a forgotten Black modernist poet—and the society of decadent aesthetes she orbited around. Shelve it near Babel: more good trouble.

You know what they say: you wait all year for a one-of-a-kind language-based magic system flexing its critiques of technology, capital, and power, then three come along at once. My book of the year was R. F. Kuang’s Babel, which doused the colonial and orientalist structures of academic knowledge production with strong measures of translation theory and anti-colonial global history, then burned the whole edifice down. Meanwhile, Scotto Moore’s Battle of the Linguist Mages uploaded postmodern occultism to the age of competitive disco-MMORPG gaming, as a champion streamer wrested the arcane knowledge of “power morphemes” from corporate and extradimensional baddies; and Robert J. Bennett closed out his Founders Trilogy with Locklands, projecting his sigil-driven art of “scriving” into a networked cyberpunk near-future that becomes all the more pointed through its alt-Venetian setting. Meanwhile, Tamsyn Muir’s Nona the Ninth came as an unexpected addition to the Locked Tomb trilogy (now surely deserving the strapline Disaster Lesbian Necromancers in Space), and I caught up belatedly with Shola von Reinhold’s slipstreamy art-historical mystery LOTE, in which a queer Black British artist fascinated with the Bright Young Things pieces together the history of a forgotten Black modernist poet—and the society of decadent aesthetes she orbited around. Shelve it near Babel: more good trouble.

Redfern Jon Barrett

This has been a pretty intense year with plenty of ups and downs, but there’s one place in the world that seems to be making steady and consistent progress: nonbinary fiction. Not only did nonbinary author Kim de l’Horizon win the German Book Prize, but gender-nonconforming fiction seems to be growing more prominent by the day. Lately I’ve been exploring the works of Cat Rambo, whose fast-paced space-operatic fiction hurls a large cast of characters into erratic and entertaining adventures, all while breaking free of gender expectations—and featuring a wide array of both alien and nonhuman species originating from Earth. My favourite has to be the highly-sensual Skidoo from You Sexy Thing, an empathic squid-being with a continuous longing for mutual affection and caring touch. A lot of us could do a lot worse than channel our inner Skidoo.

This has been a pretty intense year with plenty of ups and downs, but there’s one place in the world that seems to be making steady and consistent progress: nonbinary fiction. Not only did nonbinary author Kim de l’Horizon win the German Book Prize, but gender-nonconforming fiction seems to be growing more prominent by the day. Lately I’ve been exploring the works of Cat Rambo, whose fast-paced space-operatic fiction hurls a large cast of characters into erratic and entertaining adventures, all while breaking free of gender expectations—and featuring a wide array of both alien and nonhuman species originating from Earth. My favourite has to be the highly-sensual Skidoo from You Sexy Thing, an empathic squid-being with a continuous longing for mutual affection and caring touch. A lot of us could do a lot worse than channel our inner Skidoo.

While Cat Rambo’s genderqueer adventures are fun and fantastic escapism, Becky Chambers’s solarpunk novel A Psalm for the Wild-Built takes a more meditative approach. Part of the Monk & Robot series, Chambers uses a utopian, eco-balanced world to explore broader questions, particularly around sentience and social good. If this sounds flat in comparison to Rambo’s works then I’ve given the wrong impression—this novel contains its fair share of wry humour, and its exploration of robot political consciousness is continually fascinating. I’m also thrilled to see positive utopian portrayals of urban landscapes, but most of all it’s the naturally gender-diverse world that really comforts and inspires: the nonbinary protagonist is quietly and unquestioningly woven into the social fabric alongside the men and women around them, and it gives an insight into a better future for our own world.

This genderqueer author will certainly be exploring more works by Rambo and Chambers in future—but there’s a lot to take care of first, as another nonbinary speculative novel will be hitting the shelves in 2023 …

Tristan Beiter

My year began thinking on the past—with Maria Dahvana Headley's excellent translation of Beowulf (2020) and William Hope Hodgson's The House on the Borderland (1908). These two books had little to do with one another, but also had some striking similarities; both were surprisingly funny takes on the persistence of the past. Headley brings Beowulf into the modern social position of the bro, transforming this dramatically Old English story of kings and giving it new relevance as a representation of our present. Hodgson's novel employs a variety of metatextual techniques that made the century-old book feel surprisingly fresh as it travels to the end of the universe and back in a poorly preserved journal. Together, they set me up for a year of thinking about the malleability of time through the echoes of the past and future in our present.

My year began thinking on the past—with Maria Dahvana Headley's excellent translation of Beowulf (2020) and William Hope Hodgson's The House on the Borderland (1908). These two books had little to do with one another, but also had some striking similarities; both were surprisingly funny takes on the persistence of the past. Headley brings Beowulf into the modern social position of the bro, transforming this dramatically Old English story of kings and giving it new relevance as a representation of our present. Hodgson's novel employs a variety of metatextual techniques that made the century-old book feel surprisingly fresh as it travels to the end of the universe and back in a poorly preserved journal. Together, they set me up for a year of thinking about the malleability of time through the echoes of the past and future in our present.

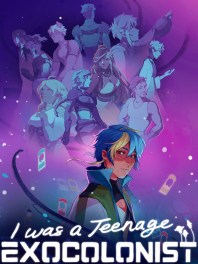

My surprise favorite piece of science fiction and fantasy this year, though, was a video game set firmly in the future: I Was a Teenage Exocolonist, made by Sarah Northway and her team at Northway Games. Exocolonist is a character-driven bildungsroman set on the distant planet of Vertumna. You play as a newly-arrived teen until the end of their teenaged years. What seems at first to be a relatively straightforward simulation of growing up, with the admittedly enchanting setting of an actual exoplanet, turns out to be a bigger story that explores the meaning of and problems with the utopian project that brought you to it in the first place. Opening as the interstellar ship the protagonist was born on crashes into the planet, the game’s characters immediately set to trying to make a life, hoping desperately not to repeat the mistakes of Earth.

The game raises questions of how to engage with the planet, taking seriously the considerations of the local ecosystem and the complicated ethical status of these people who are trying to construct a more egalitarian society while also being potentially dangerous and destructive outsiders in a new world. It manages to tell a story of the potential problems of space colonization while holding out hope for a relationship to Vertumna that respects the planet as an entity in its own right through the lens of the first generation of humans to live there, the ones that are neither of Earth nor elsewhere. The characters are dynamic and delightful, including deft and detailed renditions of classic science-fictional types: the tortured scientist, the defender of the colony, the ambitious visionary, the partisan of the planet. As the characters grow, the protagonist is able to grow with them, allowing the player to work through both the ramifications of the exocolony and teenagehood through repeated iterations that make the most of the timeloop structure, allowing us to live through the protagonist's teenage years over and over. This dimension is what allows it to feel apiece with the tone that began my year, as the protagonist's growth becomes shaped by who they would become in their other futures, playing out these temporal ripples to let us consider them in our own imagined worlds.

Nicole Berland

The premise of the Apple TV+ series Severance proceeds from a thought experiment: What if there were a technology that could sever our work memories from all of our other memories? Which companies would biohack their employees, and who would consent to such a procedure? How would it impact the workers in the office (or “innies”) and the versions of themselves who only live outside the office (“outties”)? Chillingly, Severance’s severed “innies” are functionally slaves—constantly at work, deprived of leisure, fresh air, the ability to go to sleep, the right to meet their families, and so on.

The premise of the Apple TV+ series Severance proceeds from a thought experiment: What if there were a technology that could sever our work memories from all of our other memories? Which companies would biohack their employees, and who would consent to such a procedure? How would it impact the workers in the office (or “innies”) and the versions of themselves who only live outside the office (“outties”)? Chillingly, Severance’s severed “innies” are functionally slaves—constantly at work, deprived of leisure, fresh air, the ability to go to sleep, the right to meet their families, and so on.

By exploring these questions, Severance literalizes the experiences of so many office workers—those of us who are encouraged to leave our individual identities, needs, and desires at the door. More, the series captures something deeper and more sinister about the dystopian conditions of contemporary labor, which increasingly ask workers to prioritize their jobs over their personal lives, even outside normal working hours. In this way, Severance’s severed employees are ideal employees. Lacking identity external to their jobs, they work for rewards like personalized office kitsch and waffle parties instead of wages.

Heading up a team with three other severed employees, Mark S. (a serious role for comedy darling Adam Scott) is in charge of onboarding a new colleague. He explains her job, which is to scan screenfuls of random numbers for ones that makes her feel certain emotions. The task should be familiar to us all. In our attention economy, the prime objective of mass media is to get and keep eyes on screens, and, of course, the best way to do so is by triggering our emotions. So their tasks look suspiciously like those with which we voluntarily occupy ourselves—scrolling, eyes on screens, often oblivious to meanings behind what we consume. This is our unpaid labor.

Severance refracts our experiences through the lens of science fiction, showing us the ways in which we fracture our identities in the service of corporate interests. In so doing, it invites us to reintegrate the parts of ourselves that go to work with the parts of ourselves that live in the world. The show is dark, weird, funny, sad, and, most of all, full of heart. Considering its commercial and critical acclaim, there’s a good chance you’ve already seen it; if not, let this be your (admittedly ironic) recommendation to return your eyes to the screen and get to work.

Marina Berlin

This year has been so overwhelming for me, both personally and on the more global scale of what's going on in the news, that I've had less time to read and watch things than in the several years prior. So, unfortunately, I feel like I didn't get to sample as many new offerings as I would have liked, but still several were noteworthy highlights.

In media, the winner of Best Thing On My Screen was Everything Everywhere All At Once, a movie that felt like it was dropped here from an alternate universe, one where SFF media wasn't dominated by corporations and a low budget and sheer creative energy could still make it to the big screen. There are not enough good things I could say about this, from the casting to the themes to the production to the script. I think more than anything EEAAO reminded me why I love SFF, how it can be daring and emotional and weird and heartfelt and heartbreaking, how imagination and honesty and ideas are what's important to me as a viewer, above spectacle. It's not every day you get to watch an instant classic.

When it came to books my two favorites were two books I'd been anticipating for a while. Tamsyn Muir's Nona the Ninth and K. D. Edwards's The Hourglass Throne, both the third books in their respective series. Nona was, like most of Muir's work for me, the antithesis of how a third book in a series should work, on paper, and yet like its predecessors was sharp and engaging and entertaining. In a series where one of the characters is literally God, half the characters are necromancers, and one of the foundational events is the destruction of Earth, Muir can make a scene where a school girl is trying to put booties on a stubborn dog absolutely fascinating.

Edwards's book on the other hand was a continuation of everything I loved about his series. Banter, friendships, adventure, romance, queer characters as far as the eye can see. My favorite thing about those books is how fun and fast-paced they are, while the relationships they depict are always so layered and complex, defying neat categorization.

Stephanie Burt

Many projected series start off well: far fewer, after seven books, seem likely to stick the landing, or to keep readers emotionally invested in the characters and the worlds we know. Seanan McGuire's Wayward Children series—as of 2022, and as of Where The Drowned Girls Go, its seventh book—feels like one of the few. The series stars teenagers who attend, or have attended, or will attend, Eleanor West's Home for Wayward Children. All these teens have visited, or lived in, magical worlds that fit their personalities and their needs—an all-candy world for a chaotic kawaii girl, a deathly quiet one for an extreme introvert, a horse world for a horse girl. Each of the teens, having been to their world, ran away, or fell off, or got kicked out: they're stuck in our mundane world again, and they miss the magical one that fit them. Except when they don't. Cora, the buoyant, moody would-be mermaid we met in Book Five, wants to give up her dreams of her undersea realm to escape her visions of vengeful mer-gods. So she enrolls—over Eleanor's objections—at the rival school in Maine designed to separate teens from their magical dreams. Of course the school has dangerous secrets; of course Cora and her new peers must scheme to escape, if they can ... except for the ones who can't. In some ways the novel is a very traditional boarding school saga, more traditional than the earlier volumes in McGuire's emotionally raw series. It's also a setup for the cosmological explanations we'll get next time out (perhaps). Most important, it's a profound take on self-hatred, among teens and among adults, and a fast-paced way to show how my antidote might be your poison, and how any adult worth your trust or your time ought to know that different teens need different things. It's fun, it's exciting, it's tragic (wait till you learn about the girl with the clocks) and of course it's heroic too.

Many projected series start off well: far fewer, after seven books, seem likely to stick the landing, or to keep readers emotionally invested in the characters and the worlds we know. Seanan McGuire's Wayward Children series—as of 2022, and as of Where The Drowned Girls Go, its seventh book—feels like one of the few. The series stars teenagers who attend, or have attended, or will attend, Eleanor West's Home for Wayward Children. All these teens have visited, or lived in, magical worlds that fit their personalities and their needs—an all-candy world for a chaotic kawaii girl, a deathly quiet one for an extreme introvert, a horse world for a horse girl. Each of the teens, having been to their world, ran away, or fell off, or got kicked out: they're stuck in our mundane world again, and they miss the magical one that fit them. Except when they don't. Cora, the buoyant, moody would-be mermaid we met in Book Five, wants to give up her dreams of her undersea realm to escape her visions of vengeful mer-gods. So she enrolls—over Eleanor's objections—at the rival school in Maine designed to separate teens from their magical dreams. Of course the school has dangerous secrets; of course Cora and her new peers must scheme to escape, if they can ... except for the ones who can't. In some ways the novel is a very traditional boarding school saga, more traditional than the earlier volumes in McGuire's emotionally raw series. It's also a setup for the cosmological explanations we'll get next time out (perhaps). Most important, it's a profound take on self-hatred, among teens and among adults, and a fast-paced way to show how my antidote might be your poison, and how any adult worth your trust or your time ought to know that different teens need different things. It's fun, it's exciting, it's tragic (wait till you learn about the girl with the clocks) and of course it's heroic too.

Octavia Cade

It’s not been the best reading year for me. A lot of the books I meant to read were abandoned halfway through—not because I got bored with them, exactly, but because, well, I really don’t know why. Reading requires effort, and sometimes it’s just more restful to sit out in the sun, in the garden, and fight with the wood pigeons for guavas. Which sounds rather more bucolic than the year deserves, but we take our victories where we find them.

It’s not been the best reading year for me. A lot of the books I meant to read were abandoned halfway through—not because I got bored with them, exactly, but because, well, I really don’t know why. Reading requires effort, and sometimes it’s just more restful to sit out in the sun, in the garden, and fight with the wood pigeons for guavas. Which sounds rather more bucolic than the year deserves, but we take our victories where we find them.

I like the guavas. I like greengage plums, too, and I grew up in a town where it was cold enough to grow them; but it’s too hot here for greengage, unfortunately. They’re the only plums worth eating as far as I’m concerned, so when I stumbled across The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar, I grabbed it. I didn’t know a thing about it but the plums. They were enough.

It was the best thing I’ve read this year. Iranian magical realism, it follows a family with three children. One of those children dies young, in a fire, and her ghost is the narrator. Another starts giving birth to goldfish. The third is caught up in Revolution. It’s gorgeously written, brutal, and in many places absolutely bleak, but there are moments of wonder that almost make up for the rest. I read it in a single day; it was outstanding. It made me yearn for plums.

Yearning was the default emotional tone for another of the best reads of the year for me: Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Indigenous Hawaiian author Kawai Strong Washburn. That, and sharks. You may not care to call sharks an emotional tone, but they are for me: something exciting, but best kept at a distance. (I’ve got no doubt those guavas have helped plump me up into a suitable substitute for seals.) When Nainoa is seven he falls into the sea, and the sharks rescue him and bring him home. His family lives in grinding poverty, trying to drag itself out of the economic and social consequences of colonialism. Nainoa and his two siblings—another trio of siblings, again—try to navigate the world in different ways, but what do those ways look like when one child has supernatural powers, and his siblings don’t? The sheer, horrific cost of trying to claw back what’s been taken away ... it’s not a particularly happy read either, but it is a compelling one.

(No wonder the wood pigeons and I chose gobbling instead.)

The third read, and the only one of them that was actually published this year, was somewhat happier. Still constrained, still absolutely conscious of limitation, but When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo is a Trinidad and Tobago-set magical realist romance which provides comparative a sense of support and relief. Darwin is a young man come to the city, newly employed as a gravedigger, while Yejide has inherited her mother’s ability to speak with the dead. Neither of them are particularly happy with their own lives, but together they’re able to help each other achieve a sort of reconciliation with their own histories and responsibilities.

We should all be so lucky.

Next year I’ll spend six months someplace south of here, someplace colder. Hopefully there will be plums, and the reading will be easier.

Anthony Cardno

According to the database I keep alongside my Goodreads page, I’m on track to have read over 130 books by the end of 2022 (still a few weeks away as I write this), across many genres and ranging in length from novellas to chunky non-fiction. I only managed to review one of those books for Strange Horizons, but it was one of the best short story collections I read in 2022: Boys, Beasts, and Men by Sam J. Miller. Other favorite short story collections: Someone in Time, edited by Jonathan Strahan; The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2021, edited by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki; Nectar of Nightmares by Craig L. Gidney; Love After the End, edited by Joshua Whitehead; God’s Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu (not speculative fiction); and Three Left Turns to Nowhere (novellas by Jeffrey Ricker, J. Marshall Freeman, and ‘Nathan Burgoine). Yeah, there’s kind of a theme there: lots of short stories by LGBTQIA authors and BIPOC authors. (At this writing, I’m about halfway through Xia Jia’s also excellent collection A Summer Beyond Your Reach.)

According to the database I keep alongside my Goodreads page, I’m on track to have read over 130 books by the end of 2022 (still a few weeks away as I write this), across many genres and ranging in length from novellas to chunky non-fiction. I only managed to review one of those books for Strange Horizons, but it was one of the best short story collections I read in 2022: Boys, Beasts, and Men by Sam J. Miller. Other favorite short story collections: Someone in Time, edited by Jonathan Strahan; The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction 2021, edited by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki; Nectar of Nightmares by Craig L. Gidney; Love After the End, edited by Joshua Whitehead; God’s Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu (not speculative fiction); and Three Left Turns to Nowhere (novellas by Jeffrey Ricker, J. Marshall Freeman, and ‘Nathan Burgoine). Yeah, there’s kind of a theme there: lots of short stories by LGBTQIA authors and BIPOC authors. (At this writing, I’m about halfway through Xia Jia’s also excellent collection A Summer Beyond Your Reach.)

Novels and novellas I especially enjoyed this year include Nghi Vo’s third Singing Hills Cycle novella, Into the Riverlands; Andrea Hairston’s stunning Will Do Magic for Small Change; Sweep of Stars, the first volume in Maurice Broaddus’ space-faring epic series (book two can’t get here fast enough, in my humble opinion); Alex Shvartsman’s fun NYC-set urban fantasy The Middling Affliction (ditto what I said about book two); Kate Elliot’s Servant Mage; C.S.E. Cooney’s wondrous Saint Death’s Daughter (ditto again the book two thing); and Seanan McGuire’s second Alchemical Journeys novel, Seasonal Fears. All of these books made me think, laugh, cry, and occasionally broke my brain.

I’d also like to mention two books that aren’t strictly speculative fiction, but certainly cross into our territory: The Next Time I Die by Jason Starr and The Burglar Who Met Fredric Brown by Lawrence Block are both primarily crime novels but incorporate alternate earths theory in very different, and equally satisfying, ways.

Zhui Ning Chang

This year, I’ve been reflecting on the slow, careful, unglamorous work that is taking apart corrupt systems and then reimagining and rebuilding better—the unending necessity of such labour, and the ways we narrate that. The stories I’ve been drawn to echo this, in that they are not so much about the flash-bang spectacle of good triumphing over evil, or individuals seizing the chance to burn down the world, but rather the “and then what?” that comes in the wake of that—the quiet, difficult, mundane moments, and the slow small joys to be found.

This year, I’ve been reflecting on the slow, careful, unglamorous work that is taking apart corrupt systems and then reimagining and rebuilding better—the unending necessity of such labour, and the ways we narrate that. The stories I’ve been drawn to echo this, in that they are not so much about the flash-bang spectacle of good triumphing over evil, or individuals seizing the chance to burn down the world, but rather the “and then what?” that comes in the wake of that—the quiet, difficult, mundane moments, and the slow small joys to be found.

In that light, there were two works that stayed with me. First is The Oleander Sword by Tasha Suri, the middle book of her epic fantasy trilogy The Burning Kingdoms. It is a powerful narrative following the excellent The Jasmine Throne, in which a captive princess and a maidservant with magical abilities become lovers and allies under the rule of a tyrant, set in a Mughal-inspired world of flowers and fire. I adore sprawling multi-POV fantasy, and Suri excels in this—making a case for the many character perspectives we cycle through, drawing attention to the varied ways in which people are impacted by violent oppression and the choices made in order to survive and resist. My favourite character is Bhumika, temple daughter of a destroyed religion and widow to her home city’s dead oppressor, who inherits a post-revolution society and has to do the delicate political work of navigating and rebuilding as tensions and threats build on the horizon. The grand narrative scale and complexity demands a slow read in order to fully immerse in its intense and unflinching journey, and it is absolutely worth it to be devastated by Suri’s skill and vision.

The second work is the short story collection Happy Stories, Mostly by Indonesian author Norman Erikson Pasaribu and translated by Tiffany Tsao. It is published by Tilted Axis Press, an independent publisher of world literature in translation, spotlighting international authors on the margins for an Anglophone readership. Happy Stories, Mostly steers away from traditional forms of speculation in Southeast Asian fiction, without any of the usual supernatural creatures or heroic legends; it leans into the strange and uncanny, often in moments of everyday life and surprising the reader with an absurdist and science fictional approach. As “a queer Toba-Batak-Indonesian poet from a working-class Christian background” (as described by Tsao), much of the juxtaposition comes from Pasaribu’s exploration of in-between worlds: queer and hetero, joy and misery, believer and atheist, almost and all. It is a playful, prescient collection that asks what it means to be happy, that questions the idea of “hampir” (Indonesian for “almost”) when the world is not built to accept one’s entire self: “So [...] for queer folks, what is happiness? Often, it becomes the bloodsucking demon, the vampir, the hampir.” One that not only features queer characters but is actively and cleverly queering form and narrative.

M. L. Clark

2022 was the kind of year that makes a body despair of our ever learning from history. We saw war crimes laid bare during Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine, heinous treatment of young protesters in Iran, rising nationalist hatred in India, campaigns of terror and bloodshed against trans and queer people in the US, state violence against growing ranks of the unhoused across North America, and surging case counts from the next phase in our pandemic in all corners of the world.

2022 was the kind of year that makes a body despair of our ever learning from history. We saw war crimes laid bare during Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine, heinous treatment of young protesters in Iran, rising nationalist hatred in India, campaigns of terror and bloodshed against trans and queer people in the US, state violence against growing ranks of the unhoused across North America, and surging case counts from the next phase in our pandemic in all corners of the world.

But maybe, just maybe, we can draw courage from our arts.

Shows like Andor and Severance spoke this year to two different kinds of institutionalized oppression—and our complicity in it. Conversely, what disappointed me about The Peripheral was the cleaner version of near-future struggle it offered, in stark contrast to William Gibson's much more class-conscious source text. I didn't pick a personal favourite in my review of the Le Guin Prize shortlist, but I'll say now that Sequoia Nagamatsu's How High We Go In the Dark and Matt Bell's Appleseed have since haunted me the most: the former a lovely meditation on how humans will create new rituals out of whatever loss life gives us; the latter an excellent exploration of how to navigate our ongoing culpability in the brokenness of worlds we're trying to make better.

And of course, Ray Nayler's The Mountain in the Sea is this year's standout fiction for me: a debut novel with the pacing of an early Crichton thriller, great depth in its subject knowledge, and an impeccable level of humanist wisdom about how our selfhood is inextricably linked to the systems of harm and healing we inhabit.

In nonfiction, we had a lot of winners, too—but I would especially encourage folks to revisit Strange Horizons' special issue on extractivism, curated by Gautam Bhatia and offering potent reflections on the work SFF is doing, could be doing, and should be doing to make use of its platform and history to help build a better world.

There were moments of fuller joy, too, of course. Ms. Marvel made writing a heartfelt family story of Partition that didn't centre whiteness look effortless (because it should be!). Willow, the TV series, keeps the original movie's quirkiness with an effortlessly expanded universe of messily striving human beings. Jordan Peele's NOPE is a fun monster-movie of a metaphor for how Hollywood consumes people. Prey is a masterclass in producing a franchise film with a perfectly self-contained mythos. And Everything Everywhere All At Once, which S. Qiouyi Lu excellently analysed for Strange Horizons, reminds us that the despair of our fellow human beings calls out for our creative presence as a countervailing force.

I don't doubt my fellow creators are already working hard to create that countervailing force in 2023, too—and I look forward to experiencing heaps of it. Goodness knows, if the last few years have been any indication, the world ahead will need every bit of constructive energy we can throw its way.

Shinjini Dey

Every year, while the genre increasingly gains popularity, receives recognition, and even finds experienced writers willing to attempt storytelling with its modes, the assemblages of the science fiction and fantasy—speculative fiction—industry seem to only grow smaller. It isn’t that the writers aren’t diverse, or that there’s conspiratorial effort at gatekeeping marginalized artists, but the writing and medium itself seems to have adopted a certain formulaic je ne sais quoi, making the pool of “cool things to read and recommend” rather small. Perhaps it is because the publishing industry is constantly under threat by the looming big five publishing giants, and formula is easier to fund than wild experimentation. Perhaps it is because the harder science fictional works have gotten a terrible reputation—and the harder, more technical, even theoretical (and strangely, the erotic), works have gone out of style. Perhaps it’s just that people are terrified, horrified, overworked, and so stressed they just want some comfort, both by the end of the book as well as the day.

Every year, while the genre increasingly gains popularity, receives recognition, and even finds experienced writers willing to attempt storytelling with its modes, the assemblages of the science fiction and fantasy—speculative fiction—industry seem to only grow smaller. It isn’t that the writers aren’t diverse, or that there’s conspiratorial effort at gatekeeping marginalized artists, but the writing and medium itself seems to have adopted a certain formulaic je ne sais quoi, making the pool of “cool things to read and recommend” rather small. Perhaps it is because the publishing industry is constantly under threat by the looming big five publishing giants, and formula is easier to fund than wild experimentation. Perhaps it is because the harder science fictional works have gotten a terrible reputation—and the harder, more technical, even theoretical (and strangely, the erotic), works have gone out of style. Perhaps it’s just that people are terrified, horrified, overworked, and so stressed they just want some comfort, both by the end of the book as well as the day.

On that note, all the best speculative works I’ve read this year have come as a surprise, and not just for their experiments in mode and style, but also for following traditions long forgotten, indeed for making them anew. I was shocked, surprised, and terribly disgusted by Naben Ruthnum’s Helpmeet (Undertow Publications). This novel, along with Alison Rumfitt’s Tell Me I’m Worthless (Cipher Press) and Julia Armfield’s Our Wives Under the Sea (Picador) rejuvenates body horror as it surveys our world of sexual intimacies, desires, anxieties, tensions, and discrepancies in all its implicit and unspoken alarms. I was also intrigued by Elvia Wilk’s Death By Landscape (Soft Skull Press), a series of essays about writing in-genre; it represents an exciting tendency in narrative nonfiction where phenomena are written about through speculative elements. The novel that absolutely astounded me, however, was Eman Abdelhadi and M.E. O’Brien’s Everything For Everyone: An Oral History of the New York Commune (Commune Editions) and I wrote quite a bit about its insurgency, which is historically situated and revived through utopianism. The novel exposed me to a world of Marxist science fiction written by its scholars and practitioners, such as Hannah Black’s Tuesday or September or the End, or her novel written with Juliana Huxtable called Life: A Novel, and even works of art. I hope to explore more of these works in the coming year.

Shannon Fay

In 2022 I read some genre non-fiction that I really enjoyed: Be Scared of Everything by Peter Counter is a fun and deeply personal essay collection about the horror genre, and Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability and Making Space by Amanda Leduc examines lore we’ve long accepted as truth. My fiction reading took a real hit this year as I was busy researching for a project, but I am almost done reading R. F. Kuang’s Babel and am really enjoying it. I am also finally playing Disco Elysium for the first time, and the hype is real; it’s very good. But honestly, I just want to get this year over with. Bring on 2023 and Hades 2 already!

In 2022 I read some genre non-fiction that I really enjoyed: Be Scared of Everything by Peter Counter is a fun and deeply personal essay collection about the horror genre, and Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability and Making Space by Amanda Leduc examines lore we’ve long accepted as truth. My fiction reading took a real hit this year as I was busy researching for a project, but I am almost done reading R. F. Kuang’s Babel and am really enjoying it. I am also finally playing Disco Elysium for the first time, and the hype is real; it’s very good. But honestly, I just want to get this year over with. Bring on 2023 and Hades 2 already!

Debbie Gascoyne

My reading year was affected quite a bit by the unsettled and unsettling quality of the year in general, and the overall state-of-the-universe. In new books, I was mostly seeking solace in comfort reading, but my most powerful and affecting reading experiences this year came from re-reading old favourites.

Among recent publications, I most enjoyed A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers. This was ultimate comfort reading: sweet without being saccharine, featuring nice, thoughtful characters treating one another with kindness. Equally character-driven, but a little more solemn and serious, was The Grief of Stones by Katherine Addison, which I hope will not be the last of the series featuring Celehar, the Witness for the Dead. Finally, I very much enjoyed a chance discovery, the Fallow Sisters series by Liz Williams, starting with Comet Weather. If I say these were kind of “Maeve Binchy meets Susan Cooper and Alan Garner,” don’t let that put you off. It does have a slight “chick-lit” feel to it, with its family relationships, low-key romance, and career moves, but with a plot arc driven by elements of myth and folklore, some familiar to readers of Cooper and Garner, some unique to the series. I thoroughly enjoyed them and am looking forward to what I anticipate will be the fourth and concluding novel in the series.

There is also comfort to be had from re-reading old favourites, even though these may not necessarily be in and of themselves “comfort reading.” I was suddenly in the mood to read Sheri S. Tepper’s Grass, which I consider one of Tepper’s best. The setting is astounding (even if the biology may be a bit shaky), Marjorie Westriding is one of the best female characters in SF, a match even for Cordelia Naismith Vorkosigan, and somehow Tepper manages to include issues of ecology, religion, class, sex, evolution, and the nature of god, without going over-the-top.

There is also comfort to be had from re-reading old favourites, even though these may not necessarily be in and of themselves “comfort reading.” I was suddenly in the mood to read Sheri S. Tepper’s Grass, which I consider one of Tepper’s best. The setting is astounding (even if the biology may be a bit shaky), Marjorie Westriding is one of the best female characters in SF, a match even for Cordelia Naismith Vorkosigan, and somehow Tepper manages to include issues of ecology, religion, class, sex, evolution, and the nature of god, without going over-the-top.

On the heels of the death of Patricia McKillip, and the subsequent commentary by many fans and fellow authors about the greatness of her work, I was inspired to re-read the Riddle Master Trilogy, which had been one of my absolute favourite works when I was in my twenties (I read them when they were first published—imagine having to wait for the second volume after the first ended on one of the worst cliff-hangers ever). I was a little nervous that it wouldn’t be as good as I remembered, but I needn’t have worried: in some ways I think it was better. Approaching it decades later, with all kinds of reading experience behind me, I was amazed at how well it stood up. McKillip’s prose is beautiful, the world, with its fractious and divided land-rulers bound to their lands and their people, is complex and beautiful. The Riddle Master Morgon’s quest for knowledge is always founded in fierce ties of love and loyalty. It’s wonderful, and I shall not wait another thirty or so years to read it again.

Zachary Gillan

“I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about this” is a very tiresome way of talking about things, but: I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about Kay Chronister’s Desert Creatures. For my money it’s the novel of the year, channeling Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X, Catholic iconography, and feminist post-apocalyptic fiction while sublimating the uncanny beauty of the Sonoran desert in prose that is likewise beautiful, sparse, gleaming, and lonely. For all that it’s a book of precarity and monsters and bloodshed, it earns a glimmer of hope that shines through at the end. And it manages all of that without ever feeling bloated or padded out, a feat I appreciate more and more these days.

“I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about this” is a very tiresome way of talking about things, but: I can’t believe more people aren’t talking about Kay Chronister’s Desert Creatures. For my money it’s the novel of the year, channeling Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X, Catholic iconography, and feminist post-apocalyptic fiction while sublimating the uncanny beauty of the Sonoran desert in prose that is likewise beautiful, sparse, gleaming, and lonely. For all that it’s a book of precarity and monsters and bloodshed, it earns a glimmer of hope that shines through at the end. And it manages all of that without ever feeling bloated or padded out, a feat I appreciate more and more these days.

To wit: elsewhere, my slow re-read of the New Weird brought me back to Perdido Street Station and Jeffrey Ford’s Well-Built City trilogy. The former is a messier and, yes, more bloated book than I had recalled. Ford’s work is a much more focused, allegorical affair, but both are shining examples of the high-minded inventiveness and urban nightmares that movement could bring to bear. If for nothing else, I’ll always love Miéville for the scene with the New Crobuzon emissaries meeting with the ambassador from Hell.

In new weird fiction (not to be confused with New Weird fiction!), I read Lynda Rucker’s 2013 debut collection The Moon Will Look Strange for the first time this year and have been kicking myself for not getting around to it ages ago. It’s an astounding collection of Aickmanesque horror; subtle, understated, and masterfully crafted stories of things gone Wrong. My favorite venues for short fiction this year operated in similar spaces: Undertow Publication’s Weird Horror, going strong in its third year of publication, is a pulpier spin on things, while Samuel M. Moss’s ergot., an online home for horror/weird fiction that leans innovative and short, launched this year and is already punching well above its weight. Both publications are full of authors to keep an eye on in the coming years, with some particularly strong entries from J. F. Gleeson, Megan Taylor, Charlotte Turnbull, Ivy Grimes, and Sean Padraic Birnie.

Prashanth Gopalan

Many of us endured the COVID years plagued by a sense of lost time, of life passing us by while we sheltered indoors for lockdowns and general restrictions to lift. Most of us used this time to reconnect with friends and family, forge new relationships, revive older ones, pick up books that we’d long meant to read, and turned to technology to help enrich our sense of community and kinship across the challenges of time and distance.

Many of us endured the COVID years plagued by a sense of lost time, of life passing us by while we sheltered indoors for lockdowns and general restrictions to lift. Most of us used this time to reconnect with friends and family, forge new relationships, revive older ones, pick up books that we’d long meant to read, and turned to technology to help enrich our sense of community and kinship across the challenges of time and distance.

As life reopened earlier this year and we began venturing out to explore the changed landscapes of the towns and cities we once knew, I found myself reflecting on how our digital identities helped sustain our connections with each other and the rest of the world through a time of strife and turmoil. Perhaps it was in the spirit of exploring the digital afterlives of our COVID experience that I spent the year reading fiction along these lines.

The Invention of Morel, a hidden gem from the 1940s by Argentinian novelist Adolfo Bioy Casares—a close collaborator with Jorge Luis Borges—had me enthralled with its one hundred pages. The haunting tale of a fugitive washing up on an unknown island and falling in love with a mysterious woman he encounters, only to discover that the island’s inhabitants are not quite who they seem, explores the possibility of love transcending human form, and of life in a digital para-reality, where virtual relationships can hold at least as much meaning as our real-life ones, and imbue the latter with pathos.

The This by Adam Roberts was so impressive that I ended up reviewing it for this publication: set in a plausible future of near-complete technological saturation, it explores the loneliness and alienation at the heart of modern life, and analyzes the appeal of joining hive-minds—capable of ensuring near-perfect equality and inclusion, but at the expense of individual freedom and autonomy—to those on the margins. Hive-mind entities, mediated by brain implants that allow synchronous decision-making across millions of members, provide a form of collective identity, belonging and security that invalidates the need for representative government, and emerge as a political force that threatens the stability and cohesion of human society across the planet.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams was a welcome distraction as the weather turned cold with the arrival of winter, and the headlines felt increasingly dire with grim tidings of war and economic ruin. A profound novel in the form of a lighthearted space-adventure caper, it reminded me that science fiction could be humorous and witty even while probing the fragilities and absurdities of society, life, the universe, and everything, and that intellectual seriousness does not have to preclude levity, but perhaps even benefits from it.

Lastly, Hangdog Souls by India-raised British biochemist-turned-novelist Marc Joan served up an intricate meditation on time, fate, and multiverse theory rooted in occult Indian spirituality, while also doubling as an entertaining cosmic horror novel adapting the culture of South India for fans of the Lovecraftian genre. To someone of South Indian descent raised at the intersection of Indian and Western cultures, it was refreshing to see elements of my cultural background expressed with verve, nuance, and inventiveness, without a heavy imprint of colonial moralism—and to encounter Lovecraftian-style horror expressed through a culture that has yet to be more widely explored by mainstream speculative fiction and fantasy writers. It was definitely the absorbing winter escape of a read that I had been seeking.

All in all, looking back on what has been an eventful year, it does feel like our species is experiencing the vicissitudes that most protagonists of speculative and fantasy fiction novels undergo: a sense of being trapped between worlds or modes of existence, as interstitial creatures navigating profound upheavals and great displacements as they reconcile the personal with the public, the prosaic with the profound, and the contemporary with the timeless.