Saladin Ahmed is a Detroit native who has written award-winning novels and comic books. Strange Horizons published one of his first stories, "Doctor Diablo Goes Through the Motions," in 2010. He donated payment for this interview to our 2019 fund drive.

This interview was conducted via Skype on September 12, 2018.

What was your first experience with comics?

My first experience writing comics—although I’ve been reading them all my life, it’s really how I learned to read, was from comics—and when I think way, way back to when I was a little kid, I think I wrote little comics before I wrote stories, so—but definitely  Black Bolt was my first comic, and the first issue of that came out—gosh, only about a year and a half ago. Not even. And I’ve been writing a lot of comics since then.

Black Bolt was my first comic, and the first issue of that came out—gosh, only about a year and a half ago. Not even. And I’ve been writing a lot of comics since then.

When you did your own little comics as a kid, did you have your own illustrations, too?

I did. I mean, yeah, I was never a super great artist, but up until I was in junior high, I tried to do both. I don’t think I knew I would be a writer rather than an artist until then.

Do you still draw sometimes, just to get a concept out?

I don’t do it for concepts, but I’ve used drawing a lot since having kids, since my daughter’s very visually inclined. She draws all the time. So I draw with her, as a way to just do something else, something that’s creative but not my job. Something that’s fun. I can’t imagine myself ever trying to integrate art into what I do professionally, cause I’m just not any good at it. And I work with such amazing artists already.

What do you feel like you’ve learned since your first comics came out, and how do you think you’re going to apply it as you write Exiles?

It’s a function of comics that what you’re seeing is always several months behind what I’m actually working on. So I’ve got Exiles #8 that just came out, and I’ve got several other scripts that are done—I’m actually working on newer projects for Marvel now. But you know, one of the things I’m learning, I guess, is that every book is pretty different. Black Bolt and Quicksilver were these very pensive books that were really about the central characters—kind of brooding, and a little bit existential. It’s a different thing when you’re doing a big team pow-bang superhero book, so I guess I just try to write appropriately to whoever the kind of character is, or whatever the kind of subgenre is, or type of superhero book it is.

How was reading Claremont’s X-Men run, y’know, back in the day—how has that helped you write a team book?

How was reading Claremont’s X-Men run, y’know, back in the day—how has that helped you write a team book?

Hugely. To the point where for some readers, my writing probably feels a little throw-backish. You know, comics nowadays have a lot less dialogue than they did when I was a kid, and I still write those wordy, Chris Claremont-style balloons. Claremont and all those 80s writers at Marvel were really a massive influence on me, and it’s really great to be writing the same characters, telling stories in their tradition, inheriting their stuff and updating it. Yeah, it’s been a massive influence.

You expressed at one point admiration for Sami Kivelä in how he draws monsters. And I was wondering what role monsters have in your stories, and how you think your way of viewing and writing about monsters is perhaps different than some other people might approach them?

Hmmm. Well, it’s interesting because—well, that’s a really wonderful question. I have two distinct approaches. One of them is that, except in instances of really egregious ideologies like Nazis and stuff like that, I’m not super comfortable with making human villains. What we talk about a lot is that you should understand your villain’s motivations, but I think if you’re really honest with that, it becomes hard to make real villains. Maybe not in realistic drama, but certainly in genre, especially in visual-heavy things like comic books or the adventure-fantasy I write when I’m writing fiction. People want to see cool things: they want to see wizards throwing fireballs or superheroes punching things really hard—this pyrotechnic violence, right? It's part of what we write. It’s what I like when I see a martial arts movie, but that has to have a target. So that’s one of the functions of monsters. Anybody who follows my work for a while will see there are a lot of times where people are fighting non-sentient creatures. The sentient kind of monster, orcs or evil aliens, you know, just feels like disparaging another people. So I tend to have a lot of zombies and robots—the ghouls in my fantasy novel are created creatures, they’re not sentient beings. For me, part of the function of the monster is to just have this non-human antagonist that doesn’t bring with it all the complications of having a human or a humanlike antagonist.

Saladin Ahmed

But the flipside is that I like to write from the point of view of monsters. I’m a Muslim-Arab man, and I think a lot about demonization—who gets turned into monsters and who gets viewed as monsters. And one of the most compelling narratives to me in all of fiction is that of the misunderstood monster. I’m going all the way back to Shelley—actually did a lecture on Frankenstein earlier this year. It was cool to talk about Frankenstein because I’m really interested in the monster, and I think Marvel is a great place for that, right? You have this history of characters like The Thing, but also for me taking some of these characters who have been villains, traditionally, and asking questions. The supervillain is the monster of the superhero comic, right? And I’m asking why are they monsters, what made them monsters, who gets to classify them as monsters.

It’s a challenge to ask those things and still deliver a traditionally satisfying superhero story. In any of those things—comics, fantasy, I’m dabbling a bit in TV now—playing with audience expectations is difficult. You want to push people, but not push them so hard that they don’t get it anymore.

Speaking of boundaries and what people think of as acceptable or not, I remember when you began to delve into pre-Code comics on Twitter, and those really insightful posts you did on the subject, and I’ve always wanted to ask what started your interest in that? How did your research into pre-Code comics change how you looked at comics today and censorship in general?

You know, it’s funny. I never had any interest in golden age comics as a kid, because I thought that was boring, boy scout stuff—it’s what I assumed. And for me, comics started with the Marvel universe in the 1960s—and even the silver age comics were old stuff to me, you know? I grew up reading comics in the 80s, so going more than 20 years back was not something I was ever interested in.

I think I was just fiddling around online one day and came across a site—there are these sites online that are massive databases of entirely scanned issues. Now, I did a little stint in grad school before running away and becoming a fiction writer, and I became super interested in archival stuff, looking at original materials. And there were thousands of scanned issues, including ads, of these old 1930s and 1940s comics. There were a couple of years where I wasn’t writing a lot and I was diddling around online—

That’s when your kids were young, right?

Right, exactly. And that’s one of the holes I went down, was golden age comics. And people really responded to those posts, and I kind of saw there was this whole hidden history of comics that was much more interesting than I had ever thought. I wrote about it a little bit, but it’s something I’d like to come back to at some point. And there are folks who have picked up some of these other characters, too, so you know, I’m not the only one paying attention to pre-Code comics. It’s because so many of them are in the public domain that people are doing fun stuff with them.

Right, exactly. And that’s one of the holes I went down, was golden age comics. And people really responded to those posts, and I kind of saw there was this whole hidden history of comics that was much more interesting than I had ever thought. I wrote about it a little bit, but it’s something I’d like to come back to at some point. And there are folks who have picked up some of these other characters, too, so you know, I’m not the only one paying attention to pre-Code comics. It’s because so many of them are in the public domain that people are doing fun stuff with them.

What are your thoughts about what the Code did to comics?

Well, I’ve written an article about that, for Buzzfeed. It’s a long, complex argument that I’d, you know, rather link to than try to summarize in a sentence, but the short version is that comics became a lot less interesting after the Code. There were literally dictates about what could be depicted politically and socially, and I think it did real damage to what might have been a much more interesting art form over those next couple decades.

What about Twitter? You have a pretty large following now—when did you get into it? Why did you turn to that specific form of social media, and what do you think you’ve gotten out of it?

I think I got into it—God, I think it was nine years ago, I think it was 2009 I got on? So I got on with a big cohort of writers who were exploring it, and it was new and exciting. And people were joking it was only for posting about your lunch, or whatever. But for me, it really became a kind of social lifeline. A connection to fans, to readers, and a way to express myself in small bursts—I mean, Twitter-writing is still writing, you know?

I’d imagine Twitter actually helps with short-length writing in, for instance, comics, where you’ve got to be pithy—

I think that yeah, there’s an economy there, sure. And yeah, Twitter was a way to keep making clever jokes, and getting an instant audience for it, and posting political thoughts, and getting an audience for that too, at a time when I really wasn’t in a place to write whole novels. Twitter was absolutely fantastic for that.

Now that’s changed a bit in the past little while—it’s become a much more toxic place, and it’s also just become more of a work zone for me. One thing about having a large following is it can’t be a personal space anymore. I can’t just tweet about being stressed out or dating or whatever. I can’t just talk about my life on there the way I did when it was just 300 of my friends and online buddies following me. Now if I do that, some Nazi has something to say about it, for no good reason. Or just—even the good responses, the volume of responses can just numb it out. But it’s still tremendously useful for me. I mean, I don’t have a website. Twitter is how I connect to the world, so if it goes away, I’m gonna be in trouble.

I’ve of course read Throne of the Crescent Moon—and I would be remiss if I didn’t ask on behalf of the readers as to where the world is in your thoughts right now, and how the time since publishing Throne has changed how you’ve thought of the series.

I’ve of course read Throne of the Crescent Moon—and I would be remiss if I didn’t ask on behalf of the readers as to where the world is in your thoughts right now, and how the time since publishing Throne has changed how you’ve thought of the series.

Basically, I went into writing that novel thinking I was writing a series, but as I tried to write a second book, I realized what I wrote was a novel that would some day have a sequel—which is a different thing than a series, right? When a writer comes back ten years later to a beloved world, that’s a different thing than when you have this binge-reading expectation of current publishing, where, you know, you’re supposed to have a book out every year, or at most, every two years. The entire time I wrote Throne, I knew I wanted it to have a real ending, and it does. I think it’s a pretty good standalone fantasy novel, but it’s definitely a glimpse into a larger world that people have hoped to revisit. And I do revisit it—I see those guys for a scene or two, when it comes to me, but it’s going to be a number of years before there’s another book, and it will very much be a sequel that comes after a big gap.

Same world, different characters, or—?

No, the same characters are going to be there. It’s absolutely the same group it’s going to be centered on, but it might feel more like, you know, The Force Awakens than Empire Strikes Back. And that’s just how it’s going to have to be. I’m very fortunate in that I’ve got a publisher, in Betsy Wollheim at Daw, who understands that, and we’re kind of working together to make sure it happens when it needs to happen, and not before. When it does, people are much more likely to see a conclusion to the series—a second, very long book rather than a series of books—sometime in the 2020s.

And, you know, I’ve been very lucky that the vast majority of readers that got to me with Throne have been willing to follow me other places, that they’re interested in my voice rather than just this one world.

Any graphic novel thoughts for the Throne universe?

You know, people have asked that a lot, and about some screen stuff, too, but I feel like that would actually—it wouldn’t be a substitute to me. There’s another book coming. That will happen: it’s just a question of time.

I might know one format you wouldn’t mind—I remember squealing when I saw Throne mentioned in the fifth edition of Dungeons and Dragons as inspiration. What is your relationship with Dungeons and Dragons? I know you’ve played D&D a long time—to what extent does it inform your idea of fantasy and how groups interact?

Yeah! I mean, Dungeons and Dragons, along with comics, are really what taught me to read—I eventually became a voracious novel reader in high school, but before that, I was reading cover-to-cover Advanced Dungeons and Dragons manuals. And you know, people like to knock the influence of RPGs on fantasy—this notion that it’s somehow less literary, or the magic is too formulaic—and I don’t necessarily think that’s true. Part of what you get when you do tabletop roleplaying is interaction, right? You get this cast. That’s a delightful thing, and trying to capture that when you’re writing dialogue is hard, because you’re just one person, trying to banter wittily with yourself.

When you played D&D, did you usually DM (run the game), or did you have a class that you tended to prefer?

When you played D&D, did you usually DM (run the game), or did you have a class that you tended to prefer?

I DMed my brothers in a lot of superhero roleplaying games—we had kind-of ongoing games because we were in the same house and we could, you know? But with my friends, I was more often a player, and I tended toward the rogue-fighter, the swashbuckler-type—all that dexterity that I don’t have in real life.

But yeah, RPGs have been a big influence on me. I’ve been fortunate enough to write for tabletop stuff—Rodney Thompson did a setting called Dusk City Outlaws, a kind of caper fantasy game. I’m looking at it on the shelf right now. Rodney’s a designer in D&D, actually, and he’s the person who had me listed in there as an influence. Writing for Dusk City Outlaws—It was fun to play with player expectations instead of reader expectations, you know?

They want to be able to interact with your setting in a stronger way.

Yeah, and you have to predict their reactions—I had to think back to my DM days, and it’s been a good number of years.

So if someone asked to look at your character sheet of life, what would they see in the alignment space?

*laughs*

Or is that something you’re not supposed to share?

No no no, I’m not an assassin, I can be honest. I mean, I’d like to think I’m chaotic good. Maybe that’s aspirational, but yeah.

One of my first interactions with you was on Twitter, watching you come to terms with being a parent—I saw you try to do your best to be a good parent and still fit in the writing—to meet deadlines, to pursue writing as a career. What are the things you think you learned in parenting young children at home, and what do you wish you could have told yourself?

I guess what I’d tell myself is to just give myself time, and it’ll be ok. We had twins, and that was particularly grueling. I never felt that the parenting part of it wasn’t happy, but trying to make writing work with it was the part that was always gruesome. So yeah, I think that if you’re going to be the primary caretaker, I think that you just have to allow yourself the fact that you’re not going to produce a whole lot for some little stretch of your life, but that’s not your whole life. You will become more productive again. That’s what I’d tell myself. I don’t know that I’d be bold enough to tell anybody else that, because I think we all have to figure out own paths.

What do your children like to read? Do they have very different tastes?

I was just tweeting that my daughter knows what the Eisner Award is now, which I recently won. Raina Telgemeier is a graphic artist for young readers, middle-grade readers—hugely popular—and she won an Eisner, and my daughter was like, “Is this the award you won?” Now she thinks it’s cool. So yeah, she’s a big graphic novel reader. She’ll read novels too, but—it’s funny, there’s this whole conversation about how the comics industry is in crisis, and that might be true in terms of the mainstream superhero comics industry, but when you look at graphic novels for middle grade kids, especially girls? I mean, there’s just tons of stuff out there, and she just reads loads of it.

My son, on the other hand, really only cares about one thing: he’s a Pokémon fanatic. So he’s got all these handbooks and guides and Pokémon comics. Given his druthers, he’d probably read just that. Always. School makes him read other things, but if he’s home and reading, I’m just happy he’s reading, you know? I think about how I was at that age, and how my dad would be like, “Hey, there’s other stuff out there.” And I will do that sometimes, but I’m a enough of a nerd that I know the difference between the Pokémon types and which regions are in Pokémon—I’ve learned a lot about Pokémon, actually—and that’s fun.

Then we have things that we read together. I’ve always got a book going at night. Right now we’re reading The Wild Robot Escapes, by Peter Brown. It’s a young, middle-grade novel about a robot—a near-future thing—about this robot who lands on an island and lives among the animals. It’s really good.

Then we have things that we read together. I’ve always got a book going at night. Right now we’re reading The Wild Robot Escapes, by Peter Brown. It’s a young, middle-grade novel about a robot—a near-future thing—about this robot who lands on an island and lives among the animals. It’s really good.

When you pick a book with an eye toward reading them for your kids, or when you see children depicted in books as characters, what are some things that you zero in on as quality or problematic portrayals?

It’s a tossup, because there are so many books that are wonderful, that I want my kids to know, that have awful stuff in them. So we talk about it. We read The Hobbit and talked about why there’s no girls in it. Or we’ll read another book and talk about the depiction of characters of color. But I do try and aggressively make sure we’re reading books that are not as problematic—there are so many books nowadays featuring authors of color or characters of color or featuring strong female characters. We recently read The Girl Who Drank the Moon, and they were just riveted, every night. The girl on the cover looks like my daughter, you know? Brown skin, big black hair. They had a blast with that book.

So you know, it’s this balancing. You want them to know some of the classic stuff, but also know what was wrong with it. And letting them see that there are people doing other things now.

So looking into 2019, what is strongest on your mind in terms of new projects?

So looking into 2019, what is strongest on your mind in terms of new projects?

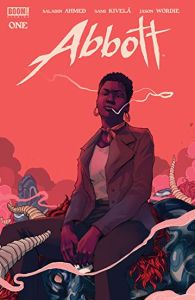

Mostly things I can’t talk about! There are a couple of pretty big announcements from Marvel—one of those will probably have been made by the time this goes to press. I’ll be writing the Miles Morales Spider-Man, so that’s one of the big things. There’s another big book Marvel will be announcing soon. And I have some creator-owned comics ideas—you know, I’m not done telling Elena’s story, so there will probably be a sequel to Abbott. And then there’s the film/TV stuff, which is always tentative and hush-hush and never means anything until it happens, but it’s been exciting to stick my nose into it.

Sound like you’ll be busy! Good luck on the secret stuff. I know we’re looking forward to seeing your writing in the next year.

Thank you.