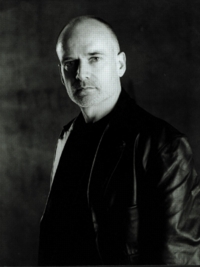

Jon Courtenay Grimwood, photo by J. Bauer |

Jon Courtenay Grimwood is one of the hottest of the new breed of British SF writers. His blend of fast, stylish action with acute social awareness is winning him praise around the world. His last-but-one novel, Pashazade, was short-listed for the British Science Fiction Association Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award. The sequel, Effendi, is a hot favorite to receive similar acclaim.

This interview took place at the British National Science Fiction Convention (Eastercon) at the Hotel de France on St. Helier, Jersey, in April 2002.

Cheryl Morgan: You seem to have a rather more traveled history than many people.

Jon Courtenay Grimwood: Undoubtedly. I was born in Malta, in Valletta, several weeks early as my mother had a water-skiing accident. Nuns looked after me for the first few days of my life as it was thought I might not live. A year or so later I went to England for a bit, but returned to Malta when I was about four. We lived there for a couple of years and I had a Maltese nanny called Carmen who spoke Malti, a form of Arabic. She used to take me through the back streets to visit her family. Carmen was the first major influence on my life. After another spell in England, my family moved to the Far East and I would fly back and forth to England for boarding school. While in Jahore I was looked after by an amah called Zinab, who was the second great influence.

We led a very privileged life, which I suspect has now gone. This was also in living memory of what the British called the Malay Emergency [a nationalist uprising]. And also a time of simmering racial problems between Chinese and Malay communities, leading to rioting and killings. Appalling levels of poverty contrasted with staggering wealth. Within one summer holiday it was possible to see dogs being strangled by collars made from wire coat-hangers, opium addicts, people living in battered shanty towns, wide-eyed children being betrothed in marriage at a very early age, and princely families so rich that they quite literally ate off gold plates.

Much later we moved to Scandinavia and lived on an island off the coast near Oslo for a couple of years. I wanted to go to university in Norway, but the authorities rightly pointed out that they could give one of their foreign student places to a refugee, which would be infinitely fairer than giving it to someone from an affluent, Western background.

Until recently I had a tiny house in the mountains of Spain. It was in an area that was once Moorish and therefore Islamic. From where I lived you could see ancient towers on the coast, and these were the towers of the Moors who were trying to defend their lands from the Reconquest.

CM: And your life has continued to be somewhat unconventional; you are a single parent.

JCG: Yes, and in fact my career as a writer is probably a direct result of that. My marriage came apart when my son was about four. When the time came for Jamie to go to school it became obvious I'd have to field him for quite a bit of the holidays. (He was still living with his mother at this point but she needed to work full time.) As a journalist/editor I had an option to go freelance, and though I tried part time work to begin with, that proved impossible, so I went completely freelance when Jamie was about nine, and he came to live with me full time when he was eleven. He's eighteen now.

CM: What sort of journalism have you done?

JCG: All sorts. I was one of the freelance writers who worked on Maxim when it first started in the UK. I've written for Esquire, quite a lot of women's glossies, and for three broadsheet newspapers, the Independent, the Guardian, and the Telegraph. At the start I needed to keep body and soul together, so I'd write pretty much anything. I did a lot of "men's point of view" stuff for women's magazines in the early-to-mid nineties, because that was what was wanted. And I wrote a lot about the Internet for the broadsheets when it first started because there were few journalists who knew much about it then. These days I mostly review for the Guardian and write novels.

CM: Was getting into novels something that you had always wanted to do?

JCG: Oh yes, but it took me a long while to do it. When I was a teenager I wrote a very bad road novel but it was so terrible I threw it away. I wrote another two books in my mid-twenties and sent them to a reasonably famous editor. He wrote back and said he'd liked the story in the first but the characters weren't up to much, and the characters in the second were good but there wasn't any story. So what I needed to do, according to him, was to go away and write something that combined good story with good characters. I was so traumatized I didn't actually try again for about ten years!

JCG: In the meantime I became a journalist and got used to getting stuff in print. So when I was made redundant from a freelance job sometime around the spring of '93 while knowing I had work to go to in the autumn, so I took the summer off and wrote neoAddix.

CM: This is one of your cyberpunk vampire novels.

JCG: Yes, set in Paris. It is the book in which I introduced my post-Napoleonic cyberpunk 22nd Century. It came out of an image that I had of a woman standing at the top of some stairs waiting to walk down to the Seine where she knew there'd be a body, and that a pathologist she hated would be there too. That was where neoAddix came from, but it was basically just me writing about all the places that I knew and liked in Paris. If there was a café I liked, then in it went. I'd also been having a series of brain scans, MRIs and stuff following some blackouts and a lot of that disquiet about being wired up to machines found its way into the novel. That said, it's a pretty bad novel.

CM: Let's put this Tarantino thing to bed, shall we?

JCG: Oh God! That was a line used by a glossy magazine to describe, I think, Lucifer's Dragon.

CM: "William Gibson meets Quentin Tarantino."

JCG: Yeah. It was perfect marketing speak so, understandably, Simon and Schuster stuck it on the first novel I did for them, reMix. And because the line was on the cover a lot of people used it. Some mag even stole it as a headline for a review, probably for redRobe. I think, it is gone now.

CM: Well, it certainly put me off reading your work for quite a while. But then I have to say that in redRobe Axl Borja kills an awful lot of people.

JCG: It's his job. He's an assassin. I should also mention that redRobe is loosely based on Under the Red Robe, a high Victorian novel by British writer Stanley Weyman. What Weyman did was encompass all of the Victorian values, and what I wanted to do was glance off the same story but encompass our values and show how different they are. So there's the name check in the title, the name of the village in the book, Cocheforet, is the same. There's a basic plot similarity between the stories. But concepts you can guarantee apply in the Victorian book: "heroic, upright if flawed killer gets the girl, repents, lives happily ever after," those don't appear. I make damn sure that Axl doesn't get the girl. (A girl gets the girl.) redRobe is about taking a story and looking at it with a different set of eyes.

CM: I really liked the gun as a character. It was good to have a major character who is an AI in a gun who is smarter than most of the other people in the book.

JCG: Oh, he's infinitely smarter than Axl. The whole thing is that he's the dominant intellectual part of that relationship. Axl is just this rather flawed guy who happens to have a much smarter friend who just happens to be his gun.

CM: And he finds much more interesting things to do with his life than being a gun, which I thought was a nice touch.

JCG: Well, I thought that if we can have reincarnation for human beings, why can't we have reincarnation for machines?

CM: And of course the main thing that comes across with redRobe is the sheer rage at the state of the world. Clearly, here is something that you have enormously strong feelings about.

JCG: redRobe was written at the height of the problems in the Balkans. The West, in its wisdom, had decided to disarm one side but leave the other side armed, and somebody used the phrase "a level playing field" to describe this situation. It was a time in which premeditated rape was just beginning to be used widely as an act of war and an act of torture. You can say that rape has always been a part of war, but I think what happened in Bosnia was a systematic attempt to destroy a society by attacking the women within that society. And the West just stood there, was shocked and appalled, and did virtually nothing.

We were meant to be helping these people. We were meant to be the United Nations. We were meant to be on the side of good, and this was just not happening. We were promising people that they would be defended. We were promising people that if they laid down their weapons we would guarantee their safety. We set up safe havens for civilians, and then pulled our troops out and wondered why thousands of men, women and children were slaughtered.

If this had been done in the days of Communist Russia, or by an Islamic country or by China, we would have been outraged and would have been passing UN resolutions demanding that something was done about it. It took a long time for what had happened in the Balkans to filter through to Western consciousness -- much longer than it should have done -- and I think there was a real attempt to make sure it didn't filter through.

CM: It still is fairly unknown. Certainly I didn't know as much about it as you have just described. But I notice that you said in your Kaffeklatsch that you read all of the papers every day.

JCG: Not quite all of them: I regularly read the Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, and the Guardian. And then sometimes the Mail and the Mirror.

CM: And this is a serious attempt to keep up with what is going on in the world?

JCG: Yes. It comes out of being a journalist. For a lot of my life the first thing I've done each day is read the papers and cut anything that was relevant to my work.

CM: How do you read so fast?

JCG: Well, you don't need to. Often the same story appears in a different form in each paper, so I read one version quite thoroughly and I can then skim the others looking for the points of difference.

CM: A common feature of your work is what has been described as "alternate future." The traditional alternate history is set in a past where something has happened to make history develop differently. You write books that are set in the future, but where something happened differently in the past so it is not our future.

JCG: That was a conscious decision. What I wanted to do was write alternate history without writing about the point of change. I wanted to talk about the point of change, probably obliquely, but have its impact felt further down the line. For my first four books, neoAddix through redRobe, the point of change is the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. In my version France under Napoleon III defeats the Prussians. Because of this, the German Empire never forms and the second Napoleonic Empire doesn't collapse. Those four books are set in the 22nd Century.

Within the Arabesque series (Pashazade, Effendi, and Felaheen) the turning point is 1915 with the American President brokering a peace between London and Berlin and what we think of as the First World War remaining the Third Balkan Conflict. But again the books are set about 40 years from now. What I have tried to do is have, not just alternate history, but alternate society and alternate politics. Obviously it is about our world and what we do. It is a way to stepping outside ourselves and saying, "if that hadn't happened, how would we feel about this. . ."

CM: It is a different approach to history, isn't it? The classic alternate history book is very much about the major events, the important players. It is history focused on kings and generals. What you are doing is much broader.

JCG: I'm talking about how society changes, and what happens when society changes. What happens if Christianity and Islam aren't automatically at each other's throats? What happens if the big conflicts in the world are not between East and West but still between France and Germany, if America remains semi-isolationist? If Russia was split in two, the way Germany used to be? Read the newspapers from the time and you can see that few in 1914 believed that within a few years monarchy would fail as the default form of government in Europe. There is a real sense in those papers that the status quo will last. And that makes me think about us, because we have the same sense of our world's permanence. That whole paper-thin Capitalism triumphant, end-of-history kick.

CM: Moving on to the Arabesque series, this is an interesting time to be a writer focusing on North African/Arabic society.

JCG: Yes, and at least one friend of mine has pointed out this may not be the best time to have novels out with Arabic lettering all over their covers. But I disagree because I think it is very important.

The Ashraf Bey books, which are crime novels set in a 21st Century liberal Islamic Ottoman North Africa are an attempt to look at what happens when Western values and a liberal Islamic society cross, and what takes place in the gaps. What happens with the politics, what happens with society, what happens with civil rights, sexual rights, children's rights? There is still a hard-line Islam within my world, but it is south of the Sahara. It is a problem for the essentially Westernized communities of El Iskandryia, Tunis, and Libya. In the same way there are fundamentalist Christian societies, liberal Christian societies and pretty much agnostic, Christian-influenced societies in our world.

CM: Do you see yourself as presenting the Arabic world to the West?

JCG: No, I wouldn't be that arrogant. What I'm trying to do with my detective, Ashraf Bey, is take a Western character into the North African world and make him understand it through the process of solving individual crimes. I didn't want him coming in and analyzing society coldly, looking at how they did this or how they did that. I want him to be part of El Iskandryia, which is why he's part Berber and part English, and grew up in New York. I wanted to put him in a situation where he is trapped between the two worlds and has to deal with it.

CM: The reader follows the same journey as the character. You start from a Western viewpoint and gradually learn more about the Arabic world.

JCG: Yes, as you go through the books, Raf learns more. He also has to take on more responsibility. A lot of the point of the series is that it is about someone coming to terms with taking responsibility rather than just watching.

CM: Raf was a gangster in Seattle, and by the end of Pashazade, the first book, he's a single parent with an adopted niece.

JCG: Yes, it is an attempt to say, "you can do all the stuff you like, but when it comes down to it and you have someone to look after, you are going to have to compromise your life to do this."

CM: Hani is a little bit of a cliché, of course: the computer genius kid.

JCG: She's representative of how I felt about having a child I needed to take responsibility for. But the business with the computers is based on a nephew of mine who I saw, at about the age of 3, toddle across a sitting room to a computer, clamber up onto a chair and hit F9 and Return. At that time I didn't even have a laptop, and I thought to myself, "you have got to get to grips with new technology, that child has just used the computer as if it were a fridge." What I am trying to do with Hani is show someone who is so familiar with technology that using it is not really an issue. The other point, more importantly, is that Hani's skill with computers is a sign of dysfunction. As a child she has had no human friends at all, she's never been allowed outside the house. Her sole connection with the outside world has been a cold, emotionally sterile aunt. Everything she knows about the world has been learnt through a screen. So Hani's ability signifies the damage in her life.

CM: So far the books have largely been about secular issues within Islamic society. Are you going to address Islam itself?

JCG: Yes, I am. What I am trying to do at the moment with the third book, Felaheen, is to look at how the puritan thread in Islam affects government. The West prefers secular Arabic governments because they are easier to understand and don't require one to understand the theocratic background to decisions. One of the reasons why putting the Taliban and Saddam Hussein in the same box is absurd is because the first is a puritan, theocratic organization and operation, while the second fears fundamentalist Islam probably as much as any Western government and has spent a lot of time keeping fundamentalist Islam down. They may both, in their way, be corrupt and corrosive -- but they are not interchangeable.

It is quite possible that if Egypt were to have a completely free vote tomorrow it might, just, become an Islamicist state, but it has governments with a very strong interest in making sure that never happens. From the Western point of view this is good. Where it becomes a real problem is in somewhere like Algeria where the government wants to stay resolutely secular and a very large proportion of the people support the Islamicists. There has been a civil war going on in Algeria for years, in which the victims have often been women and children, but it has been largely unreported.

The problem we have in the West is to understand why what we call "fundamentalist Islam" is increasing in popularity. Because I don't believe that Islam is necessarily hard line, any more than Christianity is necessarily fundamentalist. Fundamentalism has influence within both, but it is not the default position.

CM: It is possible, of course, that some areas of America would vote for a fundamentalist Christian government if they were given the choice.

JCG: Yes, and that creates a problem in European understanding of American culture. There seems to be a strong strand in America of Creationism, the idea that Darwinian theory is one faith among others. From a European point of view that's difficult for people to accept.

CM: I have only just bought the second arabesque, Effendi, and haven't had time to read it. Perhaps you could tell me a little bit about it.

JCG: The first third of Effendi is the last third of Pashazade seen from a different angle and through a different character's eyes, because I wanted to subvert what Raf took for granted.

Basically Hamzah has been charged with murder and Raf has to investigate the crime. Obviously enough, this does nasty things to Raf's relationship with Zara.

(Hamzah is a smuggler and criminal made good who is now trying to launder his money and become respectable. Zara is his daughter, the girl who Raf was going to marry in Pashazade and didn't. Zara had spent two years at college in New York and came home to find that her parents had arranged a marriage for her. She didn't want to marry Raf, so he refused to marry her, not understanding, being new to El Iskandryia and being Western himself and therefore not very clued up, exactly what this would do to the reputations of Zara and her family.)

The back history is set during the Little Wars, which are based around North Sudan. These were fought over water and the moving of borders to take in water supplies. I've interleaved a crime novel with flashbacks about the use of children as soldiers.

So we have the Little Wars running all the way through Effendi. And that strand is based around a child's idea that it might be possible to turn off the Nile, and if one succeeded in that there would be no water so the war in which he is fighting would have to cease. It is the idea of an eight-year-old. But that childish logic is tied into crimes being committed years later, and we see how the two stories interact and connect.

CM: The third Ashraf Bey novel is also the food book, as I recall you telling me.

JCG: A substantial amount of the third book is set in a kitchen. Where Raf is investigating the death of a pastry chef, while simultaneously trying to stop the fall from power of the Emir of Tunis, the man who may or may not be his father.

CM: And you did an awful lot of serious research for it.

JCG: I research each book fairly heavily. I made a trip to Tunis. And I used to work in a kitchen. If a meal is mentioned then I've cooked that meal. Gone out, bought the ingredients and actually made it. Because otherwise how can I describe how it is made or what it tastes like? Another thing I do when setting a book in a particular society is go out and buy lots of music from that culture. So I have a lot of North African dance, a lot of Sufi, and a lot of Berber music, to get a sense of it.

I also read a fair amount of the poetry, and hunt down restaurants and bars and go and eat there and ask people for recommendations of traditional dishes. I think you get a lot of sense about a country through its food.

One of the things I love about North African cookery is that the armies of Islam took their cookery to Spain, where there were was a richness to the ingredients not found in North Africa. So North African cookery exploded under the new Spanish influence. When Isabella of Castille threw the Moors out of Spain, their cookery went back to North Africa, but it came back with all of the additional Spanish richness. So what you have in modern North African cookery is ancient North African cookery, filtered through Andalusia, and then re-adapted to North Africa. You have an entire history of conquest, re-conquest and exile, perhaps just in one dish.

CM: There are strong moral themes running all through your books.

JCG: I've had reviews of redRobe that claimed Axl was too moral, that he was immoral, and that he was amoral. Somebody actually asked me once why I write morality-free characters. I don't think that any of my characters are morality free. I think they have very strong moralities, but maybe not those of the society around them. Axl has a very strong morality created by his childhood and by his relationship with the Cardinal. It has a strong internal logic.

I think the duty of a writer is to get inside the heads of every character in the book, and not just the hero. I think if you have one character with whom you sympathize and who reflects the society from which you come that is a limitation. Even your villains should be understood. They can still be evil, they can still be bad, but it is the writer's duty to make the reader understand, at some point, why they are like that.

CM: The Cardinal, for example, thinks he is doing the best thing for the world. He thinks that the world needs him in charge of it, and that sacrifices must be made to maintain his position. That's a very easy trap for a political leader to fall into.

JCG: He sees himself as indispensable and everyone else as naïve, and therefore he has to take all of the hard decisions for them.

CM: I can see that people would look at Raf and say, "this guy is completely amoral, he was a gangster in Seattle, so how come he's suddenly looking after a nine-year-old kid?"

JCG: He doesn't come to it willingly but Hani is the first person with whom Raf has a relationship where he gets nothing material back. She is his first brush with humanity. Up until then Raf has been institutionalized: in boarding school, which is a sort of prison, in the Triads and in an actual prison. The first time he stops being institutionalized is when he refuses to accept what El Iskandryia has planned for him. He refuses to marry Zara, and in doing that he steps outside himself and can start to take responsibility for his actions.

CM: So his character evolves.

JCG: Well morality is learned, just like identity. I believe very strongly that identity is created and learned. It is very easy for me to sit here comfortably, in a lovely hotel on a very rich island talking about morality. But the same me without water will react to need very differently, and will become someone else. There may be an intrinsic, unbreakable core that is Jon Courtenay Grimwood, but I'm not sure I even believe that. I may have some basic core beliefs, but these can be influenced and changed. Otherwise it would not be possible to create soldiers.

CM: Where do you go from here?

JCG: Well I have just been taken on by Mic Cheetham, and given that she agents for people like Iain Banks and China Mieville I'm hoping good things are going to happen sales-wise. I am about six weeks away from finishing Felaheen, my third book in the Arabesque series. And then I am going to do something different. I'm not quite sure what. Maybe something a bit bigger. And when I have done that, I'll probably come back to Ashraf Bey and El Iskandryia, because I have a whole series of stories I want to tell. Raf won't even be the main character in the next three. The books will be set five years in the future, so Raf and Hani will be five years older. Things will have moved on, society will be different, and there will be whole new opportunities and pressures.

CM: When you say "something a bit bigger," do you mean a longer book, or a broader canvas, or what? Most of what you have written to date has been very tightly focused.

JCG: I think a bit of both. I don't want to lose the focus, but I want to spread. I want to be tightly focused in three places instead of just one. Maybe make a time slice across centuries rather than decades. Perhaps alternate universe rather than alternate world.

CM: We are not talking space opera here.

JCG: No, I don't think I could do that. I suspect that if I tried to write space opera I'd end up with a tightly-knit, angry society within a generation ship. I'll stick to what I'm good at.

CM: Jon Courtenay Grimwood, thank you for talking to Strange Horizons.

Cheryl Morgan's native habitat is the UK, but the species has also been found in Australia and is currently infesting California. Government officials say that there is nothing to fear, save for the possibility of the Bay Area sinking under the weight of Ms. Morgan's book collection. She is also the editor of the online science fiction and fantasy book review magazine Emerald City.

Visit Jon Courtenay Grimwood's Web site.