Someone once described an object standing up high, hanging partially over an edge, as being an example of potential energy. In so many areas of the world right now, we are like one of those objects: likely to fall, the potential energy just buzzing; and if we avert our eyes for much longer, some earth tremor or jet flight will tip the balance. It will fall—we will fall—possibly irreversibly, while we aren’t looking. In this moment, we can still spin that potential energy away from the precipice, push things in a new direction, if we work fast, countering that potential energy with our intent, if we can just get more of us pushing together. To do this, we have to imagine new directions. The future is coming, faster than we want it to, and we can and should decide which direction it goes.

Art is one of the ways we do this.

When people think of art we often think of it with a capital A; paintings and illustrations hanging untouchable in a museum or gallery. Or we think of it in terms of history gone by: the mosaics in the Blue Mosque, the terra-cotta soldiers, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But art doesn’t have to have a capital A; even some of the paintings held safe in the hush of museums were once radical statements of new ideas. Art can, and should, be a means of radical transformation and questioning, and it’s everywhere, if only you look.

Not all art is fine art, and not all fine art is found in museums and collections.

In their book Speculative Everything, Royal College of Art professors Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby plot a spectrum of probable/plausible/possible futures—and posit, somewhere within these ranges, a preferable future. Depending on who you are, this could lie in any number of directions, determined by any number of considerations. If, for example, we wanted a future in which global warming is stopped and even reversed, we might imagine a preferred future in which all industry is regulated intensely and all transportation is entirely renewable. Dunne and Raby describe how most “preferable futures” in our present world are decided by government and industry: but in any sane world, this would only be part of the equation—in fact, it’s important to imagine preferred futures, no matter how unlikely, in order to find our way in that direction.

Dunne and Raby look at these future possibilities entirely through the lens of design. They take apart the notion that a designers’ function is forever to solve problems for small, capitalistic issues; instead, designers could (and should) be working toward larger, more ingrained issues of culture, climate, and geography. Instead of designing for a known future, we should aim for a possible future which may or may not be immediately accessible, thereby nudging that future closer into being. They call this Speculative Design, a subset of Critical Design, which they describe as “critical thought translated into materiality. It is about thinking through design rather than through words and using the language and structure of design to engage people.”

“[We can use possible futures] as tools to better understand the present and to discuss the kind of future people want, and, of course, ones people do not want,” Dunne and Raby claim. “They … are intended to open up spaces of debate and discussion; therefore, they are by necessity provocative, intentionally simplified, and fictional.”

Dunne and Raby say they “rarely develop scenarios that suggest how things should be because it becomes too didactic and even moralistic,” creating a shuttered scenario that is too specific to cause continued change. Instead, they describe using probable/plausible/possible futures to break out of preconceived strictures and imagine directions that, even if they aren’t likely, could foster new ways of thinking about where we want to go—our preferable futures.

Instead of designing for a known future, we should aim for a possible future which may or may not be immediately accessible, thereby nudging that future closer into being.

“Although essential most of the time, design’s inbuilt optimism can greatly complicate things, first, as a form of denial that the problems we face are more serious than they appear, and second, by channeling energy and resources into fiddling with the world out there rather than the ideas and attitudes inside our heads that shape the world out there.”

Think of those contests where children are asked to create posters depicting ideas for ways to solve world problems. So often, we don’t take them seriously except as a learning exercises for the children themselves—the ideas they envision seem sweet and silly, following improbable leaps of technology or oversimplified ideals. But if you look at them through the lens of probable/plausible/possible, they become more. They are solving problems, yes, and the children may not know how to go about making their ideas happen; but they are using art to envision a different outcome than what we have presently. Michio Kaku, in Physics of the Impossible, says there are three kinds of possibleness, and that in the most extreme version, there are only two impossible things: perpetual motion and precognition. “All other changes … are not impossible but difficult to imagine how we would get from here to there … [and so] a believable series of events that led to the new situation is necessary, even if entirely fictional.”

So perhaps we should be emulating those children, rather than smiling at their naiveté. Perhaps the key to our preferred futures is in dreaming, in coming up with visions, even if they are so implausible as to appear impossible. There is a reason why fantastic and speculative literature and media are at an all-time high. Right now, Dunne and Raby say,

the “younger generation doesn’t dream, it hopes; it hopes that we will survive, that there will be water for all, that we will be able to feed everyone, that we will not destroy ourselves … There is a growing desire for other ways of managing our economic lives and the relationship among state, market, citizen, and consumer.”

Science Fiction and Fantasy , and their related fanart, fanfic, cosplay, gaming, and so on, are integral to dreaming, to thinking of alternate realities to the one that seems here so inevitable. By providing both positive (if impossibly ideal) environments (think Stardew Valley) and negative visions that make our world seem normal and sane by comparison (think The Last of Us), the game industry, for example, actually makes us think about what we do and don’t want: some games, like RimWorld or Frostpunk, or even Oxygen Not Included, allow players a more freeform setting to explore what their ideals are: you can make a fascist colony, you can use people as resources and let them die (it’s often more effective)—or you can build something the hard way, with the needs of your colonists in mind. It raises questions about nature, humans, the role of government, and so on, and helps people explore possible futures. Even the simple, populist art of memes allow us to communicate our preferences and reinforce our ideals—and our vision of Hell.

Comics, too, have always been a medium of possibility. From the early pulp comics to Ronin’s horrible blob of always-growing capitalism, from Indian comics about Hindu gods to the bio-fantasy of Saga, from The Drifting Classroom’s horror and regret to Judge Dredd’s lack of regret, comics look at alternative realities and hold up a mirror, inviting us to look at ourselves where we stand now.

For many years, fantastic or speculative art—whether written, performed, drawn or painted—was denigrated by Western culture, despite the fact that scientists, whom we worshipped at the altar of Progress, were often the biggest fans. Those same nerdy teens who read comics and watched science fiction and fantasy movies were the ones who built rockets, joined the Science Club in school, and grew up to become the people who pushed science forward. They built the world we have now, through dreaming and designing and just wondering; and although both scientific ethics and the structure of scientific funding limit the direction and speed of research, the more speculative ideas are still being dreamed about. Many of the really big projects in science and engineering got their start as a gleam in an artist’s or designer’s eye: rockets to the moon, flip phones, and flying cars are some of the

obvious ones, but what about optogenetics, cybernetics, or even Dolly the sheep, reflecting the living sheep that Deckard, in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, obsesses about getting to replace the electric sheep that he keeps on his roof.

In 2005, Bruce Sterling described the efforts of prop-makers and art-directors on the sets of such productions as Star Trek as “Design Fiction,” a way of creating the look of the fictions we see so that they are believable, and thus, in some senses, truthful. He describes Design Fiction as “the deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change.” In other words, deliberately using objects that are elements of a fictional world, to help us believe there are other futures/ways of doing things than those we are used to.

It was Julian Bleecker, in 2009, who really made the term stick, however, in his 2009 essay (and connected essays on a similar topic) Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design Science Fact and Fiction, in which he talks about design being a way to embed imagination in material things.

“[Design] looks to be able to straddle the extremes of hard cold fact (engineering) and the liminal, reflective and introspective (art). Design plays a role across this spectrum in various specific ways. There is no single, canonical design practice that is found across this range. But, just as there is “computer design” or “database design” or “application design” as it pertains to the world of science and engineering; just as there is design to be found in the routines of art making … we can say that design … is a practice with the ability to travel and be taken up in various creative, material-making endeavors … There is an incredible malleability to how I can make design into something that is useful to what I do, which is making new, provocative sometimes preposterous things that reflect upon today and extrapolate into tomorrow.

“From this starting place, I think of design as a kind of creative, imaginative authoring practice–a way of describing and materializing ideas that are still looking for the right place to live.”

He wonders, “If design can be a way of creating material objects that help tell a story, what kind of stories would it tell and in what style or genre? Might it be a kind of half-way between fact and fiction?” He then goes on to posit that science fact and science fiction are quite closely related in practice, and that they might actually be two approaches to the same goal.

It’s a good set of questions. Design is a good place to stand and look at both art and science, if one chooses to see them as separate. It depends on one’s point of view of both. If you prefer Mach’s statement, “where neither confirmation nor refutation is possible, science is not concerned,” then you are not going to be able to get to science from art anytime soon, and in fact, you are unlikely to solve the conundrum of preferred futures, either. The scientist who feels this way is likely to work, like Oppenheimer did, without any examination of the overall, far-reaching effects their research will have on the world.

If, on the other hand, you prefer to follow, say, the Third Culture movement, where it’s believed that despite C. P. Snow’s postulation that science and the humanities have become split into “two cultures,” it is actually possible to position science in an integrated place with literature and art, then you might actually be able to do what Bleecker described with design: make changes in the direction of the future.

If the work of science is to make order, then the work of art is to chop order up and examine the pieces, and then put them together in a completely different way. Science looks at things from the outside (objectively) and extrapolates from there, while art looks at the same things from the inside (subjectively) and extrapolates completely different conclusions. There is a yin and yang here, a symmetry of examination that seems, perhaps falsely, to be meaningful. Without the humanizing elements of art, science could become just a series of taxonomies leading to knowledge for the sake of itself, without self-examination or a sense of gestalt.

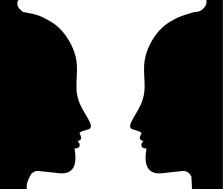

Gestalt, a German word that means “shape/form” or “whole,” is both a type of psychology and a set of design principles based on psychology. For example, when humans see a group of objects, they tend to see the entirety before they see the individual objects. In design and art, Gestalt theory is the examination of how we perceive: our tendency to see a whole before the parts, the tendency of our minds to fill in gaps, and so on. In Gestalt, if you want to  change someone’s perception, don’t try to change it all at once. Find a way to get them to see an alternative, and then work to strengthen that alternative view, while weakening the original. For example, in this image, known as Rubin's Vase, your mind will flip back and forth between what it sees (a face? Or a vase?), and then it will eventually prefer one version over another. But by changing how it is colored, placed, or emphasized, the artist can change what your brain prefers, thus in effect changing your mind. Or, in another version, you can stand back and allow people to perceive connections between things by setting groups of objects near each other, creating a whole out of these connections while still allowing contrasts between the parts and the whole. In Gestalt, as the psychologist Kurt Koffka said, “the whole is something other than its parts.”

change someone’s perception, don’t try to change it all at once. Find a way to get them to see an alternative, and then work to strengthen that alternative view, while weakening the original. For example, in this image, known as Rubin's Vase, your mind will flip back and forth between what it sees (a face? Or a vase?), and then it will eventually prefer one version over another. But by changing how it is colored, placed, or emphasized, the artist can change what your brain prefers, thus in effect changing your mind. Or, in another version, you can stand back and allow people to perceive connections between things by setting groups of objects near each other, creating a whole out of these connections while still allowing contrasts between the parts and the whole. In Gestalt, as the psychologist Kurt Koffka said, “the whole is something other than its parts.”

In science, this theory of Gestalt could be applied to change how science is taught, how it’s practiced, how it’s examined. Many people, including many scientists, tend to see science as a clear, clean, unquestionable realm of expertise, a factual system of hypotheses, experimentation, and proof; the structuralist vision of science lingers, telling us there is no deduction or logical leaps to be made in science, and very little synthesis of disparate ideas found elsewhere. In actuality, however, some of the best scientific discoveries have been made when different people from different areas of study begin to talk to each other and inspire collaboration, either within the scientific community or between scientists and others from other fields of study entirely.

These recent cross-platform discoveries emphasize our ability to stand back and allow our brains to make that leap, or connect those disparate concepts, or see the shadows around the back of existing preconceptions. Sideways thinking can make science better. And this is where art training can change how we think, and change how we see science.

If we were to fund art in schools, if we were to make students take an art class for every two science classes (and make it worth doing), we might start to see new directions forming in our possible futures. But more than this, we need to encourage cross-pollination and expanded thinking. We need to use magazines like New Scientist to teach secondary school students to read about science’s ideas, to understand it’s not all crunching numbers and filling test tubes but actually thinking and inquiring. And we need to make art education more rigorous, not an elective but a requirement. Art classes need to step up and teach more than technique and materials, but actually thinking and inquiring. We need to become bilingual.

In order to do its work properly, though, both art and science have to be taken out of enshrinement and made available to everybody. Science needs to come out of corporate back rooms and research institutions and into living rooms, as it once did with public television. Art cannot exist solely in galleries with high prices, remote and nonsensical for the average person. We all need to understand what art can do, and that we can all do it, and that the thinking that we learn to do through art can change how we think of everything else. Protest art, comics, guerrilla art, public art, projected art, cheap paperback books, online poetry, television shows—these are all opportunities to use art to make people aware of alternate ways of being. Not only do they question what is now, they present alternatives, show us different ways to proceed. Never before have we had such an explosion of technology that allows us to share art, to get it out into the world, to imagine different plausible or even implausible futures.

So this is the key. We’ve been doing it all over the place, but we need to make it conscious: we need to imagine more futures that seem implausible to us, because we need to have those visions in order to make new futures. Without the visions, the dreams, the impossible possibilities, we can’t see clearly enough to move in any direction but the same tired ones we’ve been handed, by people who don’t have our interests at heart. Keep dreaming, people. It’s the only way forward.