TABLE OF CONTENTS

Theatre

1. Gormenghast, a 1998 rock opera by Irmin Schmidt

Radio Plays

4. Titus Groan and Gormenghast, two 1984 plays by Brian Sibley for the BBC

5. The History of Titus Groan, a 2011 Classic Serial by Brian Sibley for the BBC

Television

6. The Web, a 1987 short animated film directed by Joan Ashworth

7. Gormenghast, the 2000 miniseries directed by Andy Wilson and written by Malcolm McKay for the BBC

Board Game

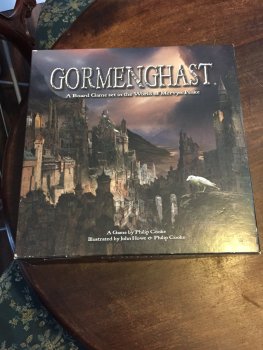

8. Gormenghast: The Board Game, designed by Philip Cooke

Artwork

9. Gormenghast Castle Automata, by Keith Newstead

Conclusion

Oh, you gentlest readers—oh, you fragile, quivering doves: this is something I have long intended to do to you I mean for you. And finally, FINALLY, due to some fools having generously donated $9,000, ALMOST A FULL DARCY-ANNUM UNIT, I can bring you a review of every adaptation of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books, not ranked because that’s a rubbish critical apparatus and this isn’t fucking Buzzfeed.

Why is it timely, you ask? It is not timely. No, it is not. However I managed to convince the chief reviews editor, the long-suffering Maureen,[1] that it could be, because Neil Gaiman’s Gormenghast adaptation is noised to come out soon. And he is Important. Don’t you think he’s Important? He sells very well, and he did Sandman half a million years ago, so I suppose he must be: important. While the production may get stuck in development hell due to my wishing very hard, just as I have cursed the last six attempts to remake Blakes 7 (or for other, unrelated reasons), it may indeed come to pass. And it would be just another adaptation, I suppose. It wouldn’t be an active unmaking of everything good in an evolving multi-authorial text like, say, Moffat-era Doctor Who. We would probably survive.

But! Wouldn’t you like to consider half a century and change’s worth of Gormenghast adaptations in order to provide context for this one? Of course you would!!

But perhaps you have not read the books? Or perhaps you have, but would like a refresher? Why, this very morning, in anticipation of your needs, I have collated my read-along tweets. We can experience these books together, virtually, and have a Gormen-blast. Ah, but perhaps these Relevant Kate Beaton Comics are not to your taste. Perhaps you seek more substantial fare: to know, in order to better weigh the oncoming Takes, how I critically situate myself in relation to the series? Well, no one’s published my long essay (co-authored with Dr Molly Katz, who shows up a lot in this essay because we did much of this research together) on the first two books as Peake’s nuanced reworking of the bildungsroman specifically via the framework of Dickens’s David Copperfield yet, so you bloody well can’t (but I swear to god it’s good).

First, here’s what we’re not going to talk about today: songs, because songs about, inspired by, or simply called things out of Gormenghast are not in and of themselves adaptations. I will point you towards a fairly exhaustive list of these (if you guessed “prog rock and metal with some emo”…), but no more shall I do. The same goes for pictures. It’s also a no from me on Titus Awakes, Peake’s wife Maeve Gilmore’s postmortem continuation of the series based on scant notes. By the same logic I’m ruling out fanfic, parodies, and texts strongly influenced by this series, because then we’d have to talk about “Lungbarrow,” and a general audience is not ready for lengthy digressions into the world of novelised Classic Doctor Who paracanon. Lastly, as a rule, I’m not going to try and review the adaptations I cannot get access to for love or money. There is a pretty full listing of these on the Peake Studies site, and a timeline as well. I will attempt to give you some idea of what it is we can’t see, but that’s about all I can offer there. A final note before we go in: the series is generally referred to as Gormenghast. The second book of that series is called Gormenghast. Several of the plays we’re discussing are called Gormenghast (not to be confused with the radio plays, which are often called Gormenghast), while the television miniseries is called Gormenghast. The main setting? Gormenghast. Got it? Good.

Two very interesting adaptations are impossible to speak meaningfully of because they never quite came together. For a while, Disney owned the film rights to the Gormenghast series. Yes. Oh yes.

(This note appears in the introductory materials of my copy of Boy in Darkness.) It's almost impossible to imagine, but then so is T. H. White’s The Once and Future King: the Disney movie. And yet. Perhaps Disney acquired Gormenghast by the same logic? I mean, they did find a Hunchback of Notre Dame they could sell as a children’s film, so anything is possible.

In somewhat less weird news, “Benjamin Britten had contemplated composing an opera based on the trilogy in the 1950s, but then changed his mind.” (This information is from the series’ Wikipedia page, but Peake Studies notes that as Britten doesn’t appear to have mentioned it in his diary, in all likelihood the collaboration had not progressed very far.) Now you’ll either mourn that as a missed trick or think “Oh, thank christ.” I am in the latter camp—but then I have no musical taste to speak of. I fell off with classical music shortly after nationalist romanticism, and don’t really acknowledge much after Brahms. I actually think Wall of Sound is a net good. Atonality? Colourism? Get fucked. Oh, wait, there’s no rhythm, so you can’t even do that successfully.

Look, some people like Love Island, we all have problems.

Speaking of both musical reinterpretations and problems, in the course of my researches I also stumbled across this. It’s more sustained than you’d think, but too eldritch to speak of.

Google at your own risk.

But there is a proper musical adaptation. There certainly is.

So you have come to the point in your life when you are listening to the surviving tracks of the atonal German rock opera Gormenghast by Irmin Schmidt of experimental rock group “Can”

Prepare an enormous rictus, y’all.

Of course this is available on Tidal (Jay-Z’s somewhat wanky exclusive-release music platform). Of course. Why would it not be available on Tidal?

Ah, but not all of it! Only selected tracks. If you do a bit of digging and are willing to fuck about with a poorly web-designed brochure, you can also find these on the official site, along with some production photos and a little video.

The visuals are big and unreal (if slightly reminiscent of the eternally-touring La Cenerentola opera production that just got yet another reprise at the Welsh National). I welcome their audacity. The design doesn’t fully work for me, but it’s a unified scheme comprised of committed choices that clearly lend themselves to the scale of opera and of the series. The design disturbs attempts to read this world as a straightforward historical setting (I suppose Gormenghast works more like Ombria in Shadow wants to, and that I’d have understood what that book might be aiming at a little better if I’d read this series first). The video shows us an arresting staging transition into “Swelter’s Aria.” The way the opera’s stage lifts to reveal the twins during the fire sequence is similarly strong, but also makes me realise how odd it is that the castle—the protagonist of the first books even beyond Steerpike (and certainly beyond Titus)—disappears from a lot of adaptations, dismissed as too difficult to convey or, at best, alluded to. Surely Gormenghast itself presents a fascinating stagecraft challenge? (Not to mention the flood!)

I find bright plastic and clear fetishwear overdone and tiring, but these are more significant costuming choices than a weaksauce Renfaire-rentals aesthetic would yield. I suppose we must remember that this was staged in 1998: the moment of the Jelly Shoe. Gertrude’s vast, spreading, biological gown is undeniably cool. Dr Prune’s gold suit, smooth moonwalking, slick hair, and falsetto are fun. Irma is absent, but Fuchsia now has Irma’s tiny glasses, which seems to suggest some fusion of the characters. If that’s what they’re aiming at, the decision doesn’t really work for me. I don’t think the opera handles Fuchsia well in general. Her solitary artistic dreaming becomes play attended by servants, which undercuts some of her definition and power (especially as Steerpike retains his big “dominating the stage” solo moment, wholly unattended and uninterrupted).

The blocking is generally nothing to write home about, and at points actively annoying. The ensemble scarf-strangulation of Steerpike at the finale is nicely executed ( ... ), though what the hell happened to the flood? The er. Staged Swelter gang rape scene, however (Is the victim Steerpike? Of course he is, everything is about Steerpike.), strikes me as a mistake born of a particular moment of homophobic critical reading. (And as very German. I believe Darren Nichols directed this. They understand him in Berlin—)

Child-Rapist Swelter was a fairly awful Take when Alice Mills explored it in Stuckness in the Fiction of Mervyn Peake, and it’s not aged well. I have a whole long argument about how this reading is shite that I’m not going to bother you with here, beyond saying that sure, you can make the details add up where you want them to—but then, and I say this as a fairly analytically (hah) committed Freudian, you almost always can when building a bijou cod-Freud conspiracy. Mills’s reading, like so many of its ilk (this is such a trend that trying to consider her interpretation in isolation would be like delving into one instance of a left Ugg boot), is predicated on a monstrous queerness that frames gay desire as chiefly pedophilic. It’s hilariously telling that in the very same book, Mills is desperate to rescue Dr Prune’s camp ass from any hint of homo. Either we’re in a hyper-real Dickensian characterisation register or all the people who might be queer-coded are sexual beings open to the same relentless literalism, Alice, this isn’t a pick ‘n' mix. You can’t say only the (frankly less queer-coded) badduns do buttstuff because Prune was fey in Fuchsia’s general direction, ergo he wants to dick her.

The opera’s staging does make some sense, because the '90s as a decade was convinced that making a text Gritty was the way to reimagine it as modern, adult, and serious. “In the grim darkness of 1994, there are only sexual assault storylines.” (Hi, DC comics!) More crucially, in the 90s two factors: a) growing awareness of and alarm at the real extent of child abuse, and b) an increasing popular awareness of therapy, gave rise to an obsession with recovering repressed memories of child molestation, sometimes via hypnosis, within American-inflected Freudian reception traditions. But as Freud had concluded in his own work and as Elizabeth Loftus showed in modern experiments, it’s very easy to retroactively construct fake memories, especially where there are strong cultural inducements to do so.[2] The bubble burst: we don’t hear much about this anymore. Choosing to make Steerpike a victim of something presented like child molestation is far more about the moment of adaptation than it is about the text. The near-contemporary BBC adaptation subtly flirts with this as well.

And what’s the upshot of all this? Are we really trying to soft-serve “poor woobie Steerpike is a baddun because he was molested”? And then is the secondary problem that Fuchsia failed to heal his murderousness (because he was sad about the evil gay) by giving him insufficient healing rich-girl pussy? Because fuck every aspect of that reading to the moon. To think I have lived long enough to see Sexy Incel Steerpike. Truly man is animal to man.

The libretto might have benefitted from engaging with Peake’s prose more substantially, and I can’t help but think Schmidt ought to have called Sting, who would have dropped almost anything else he had going to collaborate on this. It’s interesting that Schmidt’s Gormenghast is rarely funny, when this was a chief pleasure of the original and a register opera is often interested in. (Unless I’m supposed to have been amused by the rape scene?)

I’ve already copped to being crap at coping with anything after Stravinsky, so you can extrapolate that the atonal bits of this opera turned me off, and that these bits:

the sheer range of "sensurround" sound is bewildering, loud, sensuous, always intriguing, especially the rustles of exotic percussion emerging from around the auditorium. If Richard Strauss had written rock music, this is what it would have sounded like—gloriously, unashamedly lush. (Rodney Milnes in The Times on 24 November 1998)

worked really well for me, after I got into the score. And I did have to get into it. It took me a few listens to enter into the spirit of it. The Peter Gabriel pop flavour of “Oxygen” grew on me. I like giving this climb sequence a full song, because that chimes well with its importance in the book. I’m not necessarily against this music being difficult, either? (Even if Schmidt apparently considers this his “easy listening” material.) That feels like a good fit or “translation” of the text.

I wish there was a fuller album, so that I could better assess the adaptation choices. As is, the decision to make Steerpike genuinely want Fuchsia (“Duet Fuchsia & Steerpike: The Birds Are Leaving for the South”) is hardly unique to this adaptation, but it’s conceptually a betrayal of the characters, and this iteration doesn’t seem to play out this decision in a way that somehow avoids that. Adaptations ought to at least respect Steerpike’s supremely self-interested hustle. Staging this as a failed romance rather than an attempt to manipulate Fuchsia does a disservice to her as well. This adaptation depicts Fuchsia as ambivalent about her ambitious paramour, and in so doing undercuts her canonical ability to see through a determined sociopath who, lest we forget in favour of woobifying everyone’s favourite skewbald fascist, quite casually contemplates raping her if he has to in the second book in order to secure power via her noble body. Also, my god it changes the whole plot if this couple can, even theoretically, just “go to Gertrude now.” And tell her what, that they’re interested in getting married? Lady Fuchsia and a servant, even a by-now high-ranking one? Way to rip out the guts of Steerpike’s plot and the class set-up that’s fundamental to the books. Still, I forgive this effort to romanticise their relationship a little more than I do the BBC miniseries’ decision because the conventions of love ballads, and perhaps the simplifications exacted by opera as a medium, seem to force Schmidt’s hands rather more.

I’m deeply turned off by the Swelter staging decision, but I’d still be interested in seeing a complete recording of this opera. Or failing that, in listening to the full score. Or even just reading the full libretto? Come on, guys.

I’m just a girl, standing in front of a corpus, trying to write adaptation theory: the John Constable stage play

So in 1992, a dark time, the long-long ago, John Constable (writer, committed urban shaman, and exactly the sort of person I’d expect to do this) pulled off an astounding condensed version of Gormenghast at the behest of the David Glass Ensemble, who performed it at the Battersea Arts Centre (hereafter, BAC). It was important, in the Tiger Lillies’s Shockheaded Peter vein. Shockheaded Peter was so influential that I attended a thousand Fringe productions et al. like it before I ferreted out Patient Zero, went to the national Theatre and Performance Archives (part of the off-site V&A collections), and actually saw what everyone was (often badly) copying. The game of telephone had gone on so long that I’m not sure a lot of the companies involved in the mimeograph process knew this anymore. Constable’s production has something like that afterlife: “BAC’s welcome revival of David Glass’ award-winning 1992 production is a reminder of the enduring influence his pioneering physical theatre style has had on scores of young companies over the last decade and a half.” [The Stage, 2007]

Have I seen the Constable Gormenghast? Have I, fuck. It’s been revived say a dozen times since (2007 at the BAC, 2011 in Edinburgh, etc.). And did anyone record a performance of and properly archive this fucking field-changing work? No. Ahaha, no. I didn’t catch the 2007 reboot because I wasn’t in the country. If only. someone had made. a fucking. recording.

Because we cannot see that play, here’s one I made earlier:

British theatre: so yeah I guess you could say the Constable-Glass Gormenghast has been the silent context of half the Fringe shows for the last 2 decades, sure

Me: so you made a copy, right?

British theatre:

Me: maybe not of the first run, but of one of the revivals, right? RIGHT?

British theatre:look performances are

ephemeral—

Me: right, so I’m going to punch you until the soft globe of your eye dangles from its warm and welcome socket like a tetherball.

British theatre:

Here, I’ll reproduce a review of the original for you. You can pretend I saw it, as I myself do regularly while crying:

Each reader creates their own images of the characters in Mervyn Peake's dark, weird trilogy about the final downfall of a degenerate, inbred aristocratic house. [A/N: This is a weird summary, but.] As a Peake virgin free of such preconceptions, the closest visual analogy I can find is that of an animated version of the more sinister episodes from David Lynch's film of Dune (this is meant as a compliment): a collection of grotesques who alternately loom, lurk and lurch throughout a labyrinthine castle expertly conjured from drapes, canes, a row of doorways and a number of moving (actor-propelled) flats.

The admirable physical discipline of the ensemble meshes with this flexible, evocative design and John Eacott's arresting score in a remarkable theatrical creation, telling the twin tales of the rise and fall of the ruthless Steerpike and the refusal of young Titus, 78th [A/N: He’s the 77th, but okay.] Earl of Groan, to be bound to the meaningless rituals and mouldering stones of Gormenghast. A cunningly-wrought gothic phantasmagoria which deservedly adds to Glass's reputation as a prime synthesist of theatre forms.

[Written for City Limits magazine by Ian Shuttleworth in 1992]

I could just read the script, but the highly variable reviews of different productions convince me I oughtn’t to. Apparently it’s quite possible to get a bad rendition of the text. Some plays resist that more than others, but this one, devised for a specific mime-influenced company and stage, is perhaps more vulnerable to it than some. That doesn’t make it a worse play, just more delicate to move, like a soufflé. Besides, I remember too well how people hated Harry Potter and the Cursed Child based off the script. That’s quite fair. The script is in places outright abominable, and I have since come to wish the writer incredible ill on account of his Christmas Carol at the Old Vic. But the actual staging was (and probably still is, with the current cast) deeply enjoyable. Some plays lend themselves to a good independent reading experience, and in some cases it’s like trying to eat eggs and flour and a stick of butter and wondering why these cookies suck.

The moral of this story is, please send me the secret goods if you have them or know anywhere at all I can go to see a video of this sodding play. And Jesus Christ we need more funding for theatre recording, at least for research purposes, because this is so stupid. It was stupid when I had to troop to the V&A archives for Shockheaded, which is old, important, making no one any money as is and should be internationally publicly available. This complete lack of a record makes even less sense.

Whatever, Titus, get a job: Boy in Darkness, an adaptation written and performed by Gareth Murphy at the Blue Elephant Theatre in collaboration with the Peake estate

You can find this pacey adaptation of Peake’s novella Boy in Darkness online. I won’t say where because I suspect it is not necessarily legally online, though attempts to remove it would be immensely wrongheaded and actively destructive to the estate. (Please don’t pull C&D bullshit if you’re reading this and can, it’s really and truly only adding to the value of your IP.) If you want to see it, have a dekko. There are some false-flags, but at least at time of non-print, you can get the whole thing.

Now, a not-phenomenal recording isn’t the live experience of theatre, especially theatre that doesn’t chiefly rely on the vocabulary of representational techniques film has accustomed us to.

While the Boy in Darkness (henceforth BiD) novella is a great length for such an adaptation, some of its features make it a hard sell. Chief among them: Titus. It is inarguably Titus we’re dealing with here. Peake dispels any ambiguity that might attend “the boy,” never named, in some of the original story collection’s promotional materials, which he probably originated and must at least have vetted. And Titus is not a particularly sympathetic protagonist. Sure, his world is stifling, but even chained by its ritual and homicidally resented by his PA, he’s the king of it. He’s not one of Swelter’s kitchen rats, and given the relative ease of his existence, Titus’s ennui, teenage petulance, and self-centeredness can be deeply annoying. Then in Titus Alone the eponymous flowers into a right wanker, all while remaining obsessed with the past glories he’s abdicated. Yet while his “Princess Jasmine without the pet tiger, the charm, or the real problems” schtick remains an issue in BiD, Titus is never more likable than he is here (barring, perhaps, a few scattered sequences in the second book). He’s a child, and so gets a pass for acting like one. He’s in legitimate peril, he’s fairly clever and reasonable, and without any decent characters around he has no opportunity to make an arse of himself by slighting them. So BiD means you’re stuck with Titus, but it’s unusually high-grade Titus.

BiD is the most outright SFFnal the world of the first two books gets, and representing “The Island of Doctor Moreau, Who Is a Sheep” on stage presents another hurdle. The perils inherent in one-man shows and physical theatre have been extensively discussed and don’t need to be reiterated here, but it’s apropos to note that Murphy is, quite capably, juggling them in his performance. I prefer this production’s physical theatre, such as the acted-out escape from the castle or the postures Murphy adopts to embody and distinguish the goat and the hyena, to the costuming the opera employed as a means of negotiating and depicting Gormenghast’s unreality. To be honest, productions set in even the real past could always do with more physical theatre touches, if we’re aiming for anything like accuracy: the gestural languages of different periods and places were extremely different. It’s a bit odd that we almost never explore that, not even where such elements change lines’ meaning (early modern English Shakespeare audiences didn’t even walk in a way we’d recognise as normal, and it does come up in contemporary plays). Stagings usually choose just-like-us immediacy for period pieces, even though certain forms of estrangement can also be valuable affects to cultivate.

Perhaps the final major hurdle for a BiD staging is that the novella’s ending is a bit of a shart. Titus like, pushes the very scary bad sheep and wins? It’s baaaaa-rely a plot resolution. This production is a bespoke collaboration with the estate, so I imagine it’s stuck with that finale. You can’t step to an author’s family and tell them Daddy’s work was at times uneven, it’s a dick move. This storytelling hewed very close to the text in every other respect as well, and perhaps we would have enjoyed the play more if we hadn't only just finished reading the story. There’s no outright imperative to be less faithful, and I’m not sure taking liberties would have improved the production as such. Yet the fact remains that the play’s production circumstances may well have foreclosed that potential avenue of resolving plot issues like the slowish start and weakish ending, and it’s possible that the estate’s supervision put some pressure on the performer more generally.

Adaptations can sometimes yield new insights into source texts that change your relationship with them. Gareth Murphy’s evocative storytelling made me see how much Titus’s escape from the castle in BiD mirrors Steerpike’s flight from the kitchens and subsequent harrowing journey across the castle roof. This drew my attention to Peake’s use of similar techniques in both sequences, and made me consider anew his efforts to present these characters in parallel. Dr Katz also pointed out that the incident in BiD where Titus nearly faints from hunger, not having thought to bring ample food for his journey, reveals how sheltered he’s been. I don’t know that we’d have spotted that without Murphy’s embodied interpretation.

Murphy’s delivery demonstrated considerable range as he guided us through the story. The pack of dogs that menace Titus on the raft was really creepy, as was the introduction of the goat (no one wants to stroke your beard, mate, stop asking), and of course the sinister lamb. Even the voice Murphy used to talk about the lamb was unnerving. At times Murphy’s delivery was, incongruously but pleasantly, laugh-out-loud funny (as per the hyena’s “bit of a dandy” line). The actor even made what Katz has called “a valiant effort” to deliver "my loins, my terrified loins!" We were very won over by this performance, glad we’d sought it out and given it a chance. Yet there were a few issues, largely textual, that kept the production in the realm of “good but not amazing.”

You can find a pretty full list of theatrical adaptations on Peter Winnington’s Peake Studies site. For example, Professor Robert Maslen told me that the 1981 Merton Floats’ Titus Alone, performed in Oxford, with the company creating sets out of their bodies, was revelatory for him. Another company, Curious Directive, took Boy in Darkness to the Fringe some years ago. The company Caraboose and the University of Sussex also apparently did Gormenghast productions I’ve no access to. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Cheers, guys.

Listen: if it’s not online, if not even the reviews are online, it doesn’t exist. If you can’t be fucked to put or keep a record of a production on your company’s site, even if it’s not work you’re proud of anymore (which does happen over time, sure, I get it), then it does not exist.

Radio Plays

The first radio adaptations of Gormenghast were Peake’s own: two plays, performed live with a full cast and orchestra in 1956. No recordings survive. A non-commercial Californian radio station (probably) used the same script in 1969. No recordings survive. You can get a copy of that script, but I have yet to drop £15 on this taunting reminder of that which I can never know. I blame Auntie far, far more for this than the indie production team. Any time there’s an opportunity for the BBC to shit on its own posterity, there it is, pants down and grinning.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation then produced an eight-episode serial in 1983. I wouldn’t know how it is, as recordings for a play done this recently almost must exist, but I cannot find them sodding anywhere (which is nearly as frustrating as lost Who episodes: someone please send me this stupid thing). But I can talk about the other two radio plays. Both are BBC productions, and curiously, both adaptation scripts are by the same man, Brian Sibley. (Sibley himself has some interesting things to say about the history of radio productions of Gormenghast and the making of his own 2011 serial.) In some ways this hails back to a quite traditional BBC practice. Television productions were once similarly “restaged”:

Director Joan Craft helmed both [the 1966 Ian McKellen David Copperfield adaptation] and the BBC’s subsequent 1974 DC, as well as many, many other Dickens adaptations. [...] There are so many commonalities between these that we might almost consider the ‘74 a revival of the same production, this time in colour (besides, the BBC may well have already gotten rid of the bulk of the ‘66’s episodes by 1974). [...] Script writer Vincent Tilsley also worked on The Prisoner, and “[g]ave up writing for television, and became a psychotherapist, when his six-hour drama ITV Sunday Night Theatre: The Death of Adolf Hitler (1973) was cut down to less than 2 hours.” Per this write-up, Tilsley is already revising his '56 script here. The 1974 script is by Hugh Whitemore. I’m honestly surprised they wrote a whole new script for that, given how akin the final products are, and wonder about the extent to which they edited the ‘66 version versus attempted to recreate their last two attempts without:

- script drafts, which the BBC is not in the habit of saving for some godforsaken reason,

- easy-to-view previous editions, or

- Tilsley’s being active and willing to play ball.

(From my review of the ‘66 adaptation.)

Thrilling stuff, eh? We have some laughs down in the British Film Institute’s basement archives. I mean, I do. Alone, there in my sound-isolated film viewing cubicle. With salad.

With that in mind, let us discuss Sibley’s firstborn. I hesitate to tell you that this play is online somewhere, because the BBC might come and make sure it isn’t for no real justifiable reason when surely they have better things to do with what’s left of their austerity-gutted budget. But it is.

It is with a heavy heart that I apologise to Sting: The 1984 radio play.

Two ninety-minute episodes. One per book (excluding Titus Alone). Starring Sting. As Steerpike. If you don’t know that Sting named his dog, his horse, and his company “Steerpike” and his daughter Fuchsia, it’s time you had this knowledge thrust upon you. Naming a horse “Steerpike” is begging it to throw and kill you, yet somehow, Sting lives. This is such embarrassing stanning that I feel chagrined for all involved (especially the horse).

With that said, I don’t think you can imagine how indignant I was when Sting was not only still with us but also really, really good in this role.

Apparently when Sting was still an English teacher his girlfriend, a big fan of the books, introduced him to them. (Dr Katz has hypothesized Sting may well be the most subsequently famous man ever to have been dated because he resembled a fictional character. Undeniably, in 1983 Sting did look like Steerpike, if Steerpike was at all conventionally hot.) I feel I have thus accidentally learned way more than I ever wished to about Sting, his then-girlfriend, and their almost inevitable tantric Gormenghast roleplay. I have stood too close to him.

Character work is one of the chief qualities of this remarkable adaptation, so we’ll start with the ensemble and then come back to Sting the Lamentably Talented. There’s a parade of good casting here—or perhaps in well-executed productions these are simply really rewarding roles. Cora, Clarice, Sepulchrave, and Sourdust are all great, but this Gertrude stands out as fabulous. But again, it’s also just a fun part? Nannie Slagg has a fantastic voice for the role, and the exiled Flay’s happy sigh when Titus says he's hungry (he gets to serve the Earl again!) is absolutely perfect. This Barquentine is loathsome, this Fuchsia is effective, and this is a startlingly appealing Titus that makes me rethink how one’s “supposed” to read the character. Titus’s child actor has quite a cute voice, and when he says the lines Titus is suddenly much more believable as the protagonist of a bildungsroman. The 1984 plays augment this effect by taking parts that work well in the second book, like the lichen fort scene, and letting us spend sufficient time in those moments to warm to Titus a little. And the trilogy does work better if you don’t hate Titus, even as Hamlet works better if you can “buy in” to him a bit and focus on his situation and dilemmas rather than getting distracted by the fact that he’s insufferable.

The second of these plays treats Bellgrove and Irma’s romance quite gently, while retaining the high comedy of Irma’s “finding TREASURES!!” in herself upon the awakening of her sexuality (Was it ever asleep? Could we help it to fall asleep?). Irma and her brother Alfred play off one another delightfully, and really Alfred Prunesquallor, with his nervous laugh, edge of camp, compassion for Fuchsia, and capacity for polite suspicion (he still calls Steerpike “dear boy” when he’s fairly sure he’s dealing with a serial murderer), emerges, quite rightfully, as a star of this production. More than Titus, Fuchsia and Prune could be considered the best examples of the moral order of this universe.

Either this production or Sting himself (he’s originally from Wallsend in Northumberland, and I could not pick “Northeastern” out of a vocal lineup to save my life) bothered to give this Steerpike a bit of an accent rather than letting his pronunciation read as posh RP. Sting’s controlled delivery is especially welcome given that the miniseries Steerpike’s accent ranges wildly. This adds some texture to both the highly classed world and the auditory experience of the play, which is particularly important given that the adaptation is of course entirely reliant on sound.

This Steerpike is also disconcertingly winning. He sounds youngish in this, with a touch of the “evil schoolboy” vibe Professor Robert Maslen draws attention to in “The Erotics of Gormenghast.” Sting gets in some fantastic line deliveries, and he’s frequently hilarious. The scene where Steerpike ostentatiously starts smoking a pipe to give the slow twins the idea to burn the library and then congratulates them on their inventiveness when they finally catch on is superbly done. Sting projects his voice, does bitchy impressions, and generally makes the medium yield telling, entertaining character moments. The play’s narration also gives us great stuff to work with here, retaining touches like Steerpike’s calling card and describing him as rolling into Fuchsia’s arms “quick as an adder” when an opportunity to curry favour presents itself.

This adaptation is more invested than the miniseries in making you feel the difficulty and peril of Steerpike’s early physical clamber up to the castle roofs. The only thing that threw me about this section was the way the climb itself was made to stretch for physically impossible days in order to jiggle the time line so that Steerpike was stuck on the roof while Titus was christened. I get why the writer tweaked the order of events here, but with that sort of timescale Steerpike would just have starved and saved everyone a lot of trouble. (Yes, I know it’s the order of events collapsing rather than Steerpike miraculously surviving for a month on Mr. Chalk’s droppings, but still.) Initially this seventeen-year-old Steerpike doesn't seem perfectly smooth and competent. He's shown to really labour to become himself. The audio aligns us closely with Steerpike’s peril, inexperience, and struggle to come into himself, which renders him something closer to a traditional protagonist.

In a scene that markedly departs from the original text but works in its own right, Steerpike is vicious to Nannie Slagg. When Fuchsia enters the room he U-turns immediately, implying that Slagg is a foolish old woman who’s misunderstood him and playing the two women off one another. This adaptation also has Steerpike poison Slagg, and it does make some sense that both audios and the miniseries want Steerpike to murder her. The change rationalises Peake’s drifting plot, which seems to trail after characters in a riot of discovery-writing and thus has Steerpike studying poisons, stealing them, and then never doing much with them. The decision also adds tension, enabling the adaptations to meet the modern generic expectations of their new formats. Textually, I suppose Steerpike might have murdered Slagg—it’s not explicitly untrue. But neither is it directly necessary, and before he cracks Steerpike doesn’t really kill for the fun of the thing. It’s significant that he begins to do so after he’s essentially lost, when he just wants to watch the world inundate. In the book Steerpike murmurs the number of people he’s killed during his convalescence, and if Steerpike had killed Slagg, then these numbers wouldn’t add up. Oddly, adaptations tend to retain this incident (you really could write around it?). But, having added a victim, they also have to add an awkward justification to make the sum work. The ‘84 play also has Steerpike considering his mounting tally of victims in a moment of cooler consideration (possibly because the change of medium has enabled Shakespearean asides, as much as anything). This more rational reflection makes him seem slightly more culpable in the death of the twins.

The 1984 plays are less firm than the source text is in establishing that Steerpike is exclusively interested in Fuchsia as a route to power, but at least they don’t irritatingly insist on a romantic reading as the opera does. The climax of the ‘84 adaptation also plays out in a way that, while not directly contradicting the original, does alter the finale’s tenor. The play uses the audio medium to let us—trained by now to recognise his voice—hear that Steerpike is disguised as the man sent into a flooded tower after him, who he’s killed. We’ve lost Steerpike’s point of view here, and yet we realise what’s going on before the other characters, who are dependent on visual confirmation, do. We also have a sense, even as this Steerpike seems to, that he’s almost certainly about to die. That knowledge undercuts the anxiety of the scene, which the book lays on very thick indeed by forcing you to inhabit the sensory environment and timescale of this sequence. With less tension choking off every other avenue of response, we can explore the conclusion’s other potential resonances.

The well-turned adaptation script and the competent actors’ comic timing make this one of the funnier Gormenghasts. Occasionally the comedy is not precisely intentional—when the passage is read aloud in a sinister, insinuating tone, the “monkey gamboling in the dust,” “swinging on the door handle with its nervous little hands,” which “doesn't drop alone,” sounds like a figure of enormously complicated innuendo. The knife fight wherein two extremely British men who talk like Leela out of Doctor Who, nominally Bright Carvers, are described as naked, gleaming, and fierce, is somehow remarkably unconvincing even though I can’t see it. I can feel that they would have cast and then oiled up John Leeson.

Overall, however, the drama and intensity of the book’s prose survives this translation process startlingly well. In part this is due to Sibley’s deft, intelligent use of his form. The frame narrative he establishes with “the Artist” allows Peake’s language to build this world via description, to smoothly intrude on the play format, and to blend dramatisation with storytelling. Little touches, like an indignant Flay exclaiming over the narrator, show a deep familiarity with what radio theatre can do (which is the natural product of Sibley’s very extensive experience). I’m accustomed to Big Finish’s occasional efforts to explore their medium, and so really appreciate this kind of formal play.

Sibley also brings in “the Artist” for his 2011 adaptation, though I find the gesture less intrusive and more successful in this earlier iteration. The BBC miniseries likewise borrows significant narrative shortcuts from the ‘84 plays. Steerpike’s poisoning Slagg, the shape of the conversation about the Thing, and Steerpike’s active role in the search for Titus when he runs away all probably derive from the this adaptation (though this last seems a fairly obvious thing to extrapolate from the text), as do a handful of other choices.

I find this the most sympathetic adaptation of the series overall. This skillful, virtuoso radio play reminds me how much I often adore '80s and earlier BBC work. The BBC’s 2000 miniseries has several good points, but I think these plays undeniably succeed to a greater extent. I appreciate that they’re capable of capturing the mood of Titus’s dreamy schooldays and the books’ disparate comedic elements—the Dickensian range that really shows Peake’s influences. The play is of course condensed, which at times strains the production a little (Sepulchrave seems to go mad in an instant), but overall it’s well paced. After all, in a sense not that much happens in these books, and there’s exceptional language to cherry-pick from in an abridged treatment. Perhaps this endeavour isn’t necessarily the needle-thread more laboured adaptations can make it seem. I can’t really access how the ‘84 would work for someone unfamiliar with the originals, but I think fairly well? It might serve as a great way to introduce the series to people.

The National Trust acquires Gormenghast: The History of Titus Groan, a 2011 Classic Serial by Brian Sibley for the BBC

If you get an Audible membership (or free trial), you can, with unusual ease for this sort of thing, access The History of Titus Groan. This six-part series gives roughly two hours and/or two episodes to each of the series’ three core books, including the dark horse Titus Alone. There’s also a fleeting reference to The Boy in Darkness (a hyena laugh when Titus mentions his wanderings, which must seem fairly random if you’ve not read the novella), a quotation from Peake’s poetry worked into the story (“I Cannot Give the Reasons”), and a frame narrative and denouement that draw on Titus Awakes, Maeve Gilmore’s continuation of the series very loosely based on her husband’s notes. Adapting Alone is ballsy, and adapting Awakes unheard of. But based on my previous good experience with his 1984 radio plays, if I trusted anyone with it, it was Sibley.

The resulting production is ambitious and, in several aspects, even more successful than Sibley’s earlier work. The Guardian’s “Radio Head” feature praised both of Sibley’s adaptations highly, commenting that they genuinely add something to the original. Ultimately, I do prefer the 1984 play to the 2011. It helps that the ‘84 isn’t lumbered with Alone and Awakes, but I also find the first version’s rendition of the initial books slightly more compelling. It’s a choice one could go either way on, though. Dr Katz, for example, feels the 2011 edged out the 1984 for her. She found it more absorbing as drama, particularly the first four episodes. Two hours per book does give the text some welcome breathing room, and very little of it is wasted. There’s a lot to recommend Sibley’s rethinking of his earlier work, including some elegant improvements on and economisations of his own earlier decisions.

History takes the 1984 play’s “Artist” narrator structure further, staging a dialogue between that figure and Titus, who find one another in the artist’s lonely island house. In his interview about the project, Sibley says this recounting allows him to explore Titus and his community’s memory and family history. (The timeline is also compressed and re-jigged in similar ways in both plays.) The setup can feel by turns contrived and particularly effective. It works well for Titus to speak about his own infant acts of rebellion, and even for him to speak about Steerpike. There’s always a trace of Hamlet about Titus, and the act of storytelling creates a “motive and the cue for passion” doubling, producing interesting layers in his performance. Including any of Titus Awakes probably forced Sibley to expand this frame narrative, and though it can be awkward, as a way of handling that material I can’t fault it.

This play generally does a deft job of bearing the structural needs of its later episodes in mind. Flay’s discussion of exile lends itself well to the wandering and longing of the Titus Alone section. Dramatically I wouldn’t have bothered with Titus Awakes—it forces a well-paced serial to finish on an long, odd denouement without a lot of energy—but the estate might well have insisted, and even if they didn’t, it’s probably good for some production to at least try working with that material. It’s also worth noting that Awakes was published in 2011 as part of the centenary celebration of Peake’s birth, that this series was probably part of the same commemorative initiative, and that this may have made establishing a relationship between the two projects seem necessary.

I might recommend listening to this longer 2011 play in installments rather than binging it, as I think this might enhance your enjoyment. I did start to worry during the course of listening about all these adaptations clouding the “real thing” for me (though Benjamin, Derrida, and a host of other people would rush to reassure me that there’s not really a definitive form of any work, and that all iterations are equally “primary”). Nevertheless, I do find it annoying when details blur: adaptations often make my memory of an original poorer.

The excellent cast consists of “Luke Treadaway as Titus, David Warner as the Artist and Carl Prekopp as Steerpike. Also starring were Paul Rhys, Miranda Richardson, James Fleet, Tamsin Greig, Fenella Woolgar, Adrian Scarborough and Mark Benton.” The line-up has a touch of the “people what we had in the studio/only twenty actors in Britain” BBC vibe, but I consider that part of the charm of UK productions. Oh, look, it’s someone named “Fenella.” Oh, and there’s Tamsin Greig again—

In some ways adaptations of the first two books rise or fall on their Steerpike ( … shut up, I didn’t name him)—like the Celebrity Hamlet phenomenon, but less tiresomely exhausted. (It would be interesting if a production of Hamlet really contested the Celebrity Hamlet Trend, interesting itself more in the ensemble than in him—if a production thought everyone else was key, and that the world of the cast, those relationships, mattered more than the absentee prince.) I do slightly prefer Sting, but have little bad to say about his successor.

Prekopp, who can sound slightly like David Tennant in his Estuary mode, is thirty-two, and so he’s Steerpike’s final book age throughout the narrative (though time of course works oddly in the novel, seeming arrested for everyone but Titus). A side note: no one ever double-casts Steerpike, though arguably, one should. Anyone who thinks an actor’s age doesn’t really matter in a radio play because you can’t see them has not had to listen to Steven Pacey or Paul Darrow in Blakes 7 reprises. Prekopp plays the seventeen-year-old version of his character as rather desperate and vulnerable: palpably young, pitiable even as he’s horrible (it helps here that they’ve kept the climb sequence long and arduous, with conspicuous heavy breathing). When Titus goes missing, Steerpike seems pressured to locate him, as though he feels on the line for it (though perhaps he just wants the credit of finding him). This is a nicer Steerpike than some. Not out of character, but taking a tack, in the way a fairly faithful Shakespeare production could tilt towards a given reading. He doesn’t necessarily seem grieved that he’s semi-passively killed Cora and Clarice, but neither does he sound completely callous about what he’s done.

Luckily this adaptation lets the character occupy a wider variety of registers than the merely sympathetic. He employs perhaps the most sinister tone of any Steerpike and a rather mad laugh, which is enjoyable even as it’s lamentably part of an annoying characterisation trend in genre fiction. He joins John Simm’s roughly contemporary “crazy” Master in Doctor Who in 2007 (and after), Sherlock’s “crazy” Moriarty in 2010, and James Bond’s “crazy” nemesis Raoul Silva in the 2012 Skyfall: scarequotes-crazy (with a touch of lavender menace) was so hot right then! The 2011 play retains Steerpike’s genuinely funny calling card, and his odd DIY touches. In the book he repairs the chairs he uses to furnish his Fuchsia Seduction Zone himself, for some reason. I guess he likes upholstering? And is he the one sewing a little outfit for Satan the monkey in this adaptation? He kind of must be? Steerpike almost needs an evil animal familiar to gloat to sooner, given the format. The audio does struggle with Steerpike’s POV in places, having to afford him a Shakespearean monologue at one point. The way the framework is set up, he can’t have Titus’s narration gig (on account of not surviving to the end). But giving the job to him would almost make more sense. This production also brings the actor back in the Titus Awakes section as a medical orderly at an asylum—a fairly professional and kindly one. What that doubling’s doing beyond saving the BBC a fiver, god only knows.

I enjoy when adaptations bring out elements of texts I couldn’t see before, and I also appreciate the social aspect of them. Discussing readings is wonderful, but different conversations emerge when you’ve experienced a play together. Dr. Katz and I debated during this listen why Steerpike keeps his poisons in a drawer in the room he’s constructed to seduce Fuchsia. After all, he could keep them anywhere else—the text specifies that he has several such hideaways. On some level, Katz wondered, does he want Fuchsia to find them? I said that perhaps he thinks she’ll find them sexy and mysterious. It’s the sort of thing he’d think, and also Fuchsia might like the queer beauty of the colourful vials and the prospect of their unknown, almost magical powers. But more likely he wants to be able to drug or eliminate her if things go wrong (again, he does explicitly contemplate rape if necessary in the book). Katz agreed that Fuchsia is unusually strong and Steerpike unusually short: if he's smart, he's not planning to physically overpower her in a crisis. After all, he couldn’t even take his loathed boss Barquentine, a seventy-year-old man with one leg. Personally, I think strong, athletic, and batshit Steerpike could take nearly anyone, but batshit-for-Gormenghast, gives-no-fucks feels-no-pain Barquentine proved an exceptional challenge. No matter how generally physically capable Steerpike is, he oughtn’t to plan on winning a physical fight with no contingency in place, and he certainly wouldn’t after the Barquentine fiasco.

This audio treats said conflict with Barquentine perhaps too centrally. Steerpike’s elaborate screaming when he’s struggling, then struggling and on fire, then struggling, on fire, and falling, then struggling, increasingly less on fire, and drowning, risks being as comic as Luke’s special edition shrieks in Empire Strikes Back. Subsequently, the audio becomes perhaps too preoccupied with Steerpike’s new Traumatic! aversion to fire. I found it a bit eyeroll, even as I understand that “fire bad, tree throbbing” is simpler to convey than the book’s description of the increasing and undetected degradation of Steerpike’s mind which eventually leads to his death. Doing justice to that is bit much to ask of a lean audio play.

More than any other version, the 2011 play puts an especially fine point on Steerpike’s “romantic” or sexual positioning as a means of social climbing via both its performance decisions and the language it uses. When Steerpike is scaling the roofs, he sees that Fuchsia’s window is “the only way in.” (Dr Katz commented that In a universe where these books are more popular, Fuchsia’s Attic is almost certainly the name of a disorganised vintage store that does books and antiques, which used to sell Wiccan shit and now sells vegan brownies.) Even as she embodies the power Steerpike lacks, it’s impossible not to feel for Fuchsia and the gentle comedy of her expectations of romance, which the audio retains.

From Titus Groan:

“I hate things! I hate all things! I hate and hate every single tiniest thing. I hate the world,” said Fuchsia aloud, raising herself on her elbows, her face to the sky.

“I shall live alone. Always alone. In a house, or in a tree.”

Fuchsia started to chew at a fresh grass blade.

“Someone will come then, if I live alone. Someone from another kind of world—a new world—not from this world, but someone who is different, and he will fall in love with me at once because I live alone and aren't like the other beastly things in this world, and he'll enjoy having me because of my pride.”

Another flood of tears came with a rush.

“He will be tall, taller than Mr. Flay, and strong like a lion and with yellow hair like a lion's, only more curly; and he will have big, strong feet because mine are big, too, but won't look so big if his are bigger; and he will be cleverer than the Doctor, and he'll wean a long black cape so that my clothes will look brighten still; and he will say: 'Lady Fuchsia,' and I shall say: 'What is it?'”

She sat up and wiped her nose on the back of her hand.

Fuchsia’s wishing for some adventurous, knightly admirer (Sibley’s kept the “and I shall say: 'What is it?'” line) is an especially awkward monkey’s paw for listeners who know the books, and thus know that she’s about to get one, and that he’ll be exactly as violent, ambitious, and disinterested in her person as the heroes of chivalric Romance, which trades in women’s status and at best their particular bodies under the banner of courtly love. The 2011 play skillfully balances Steerpike’s interactions with Fuchsia alone against his interactions with her in company, highlighting an early occasion on which he distinctly gaslights her while he’s pressuring her to vouch for him professionally. It is interesting, however, that by and large not even good adaptations deal well with Fuchsia. At best she becomes less central to the text, her perspective less delicate and sympathetic, and her occasional piercing ability to undercut Steerpike’s web of spun bullshit gets lost. When people are making decisions about what’s important, what to retain and what’s disposable, why is it Fuchsia, such a core component of the text, who always ends up on the chopping block? (I mean, I’m fairly sure I know why, I just want to draw attention to it for a moment. More on this in the treatment of the miniseries, which is the worst about it.)

In terms of performance, this Steerpike verbally lays on the sex appeal to get hired by the Thirsters Prunesquallor. It’s a fair reading of the text. Steerpike’s delivery drips with willingness to fuck Irma (I mean he would if he had to, probably, but it never becomes textually necessary), and then in an instant he turns to her brother to campily ooze that “hanging about” is “one of the things I never do.” It’s not explicit in the book that interacting with Steerpike (and then failing to close the deal) made Irma want to get married, though it’s certainly possible. This audio just flat out says it, which—fair.

As you might expect given the reputation of the actors attached to the project, all the characters are strong. Gertrude is magnificent, at once the embodiment of Gormenghast’s steady presence and supremely annoyed by the people around her who comprise this micro-civilisation, flatly interrupting tedious rituals with an authoritative “How much more is there?” and a “Louder, Sepulchrave” when her husband’s muffled Ritual Statements aren’t getting the job done. (This is when Slagg, out in the hall, needs to be ceremonially called so that she can bring the infant Titus in to be wrapped up in the book of ritual, like a chicken folded into parchment paper for roasting.) Gertrude’s cat—the one that takes a chunk out of Steerpike’s face when Flay throws it at him—remains perhaps the most efficient character in the books. It zeroed in on the trouble maker, took action, fucked up Steerpike’s face, and didn’t even die for it. Suck it, Barquentine. For his part, Sepulchrave sounds sufficiently “more depressed than even I, a depressed person, have ever managed to be while standing upright.”

While we’re on the family, this is perhaps my favourite Cora and Clarice Combo of any adaptation. Their dialogue is funny and creepy, often simultaneously (“Powah, powah, powah!!!”), and has a perfect overlapping and unnerving twinnish patter. “Thinking—that's what we've been doing—thinking a lot.” One does wonder why no one finds them a few servants, just to shut them up. I suppose no one needs to, because no one really cares about the twins’ bullshit. One also wonders why, even in the book, no one ever calls them out for not showing up to Titus’s party cum arson cum Master of Ritual execution. It’s fairly suspicious. Again, I suppose no one pays attention because the aunts are irritating even for Gormenghast (what a distinction), and thus no one cares. Less charitably, it might be because while Peake’s discovery-based compositional technique makes for startling imagery and character moments, it does not particularly lend itself to airtight plotting. We all have to sit here pretending that Steerpike’s clever because the narrative insists he is rather than concluding the obvious: that only an outright idiot would concoct a plan that relies on the intelligence, discretion, and reliability of Cora and Clarice. I would sooner trust a biscuit left in tea not to lose structural integrity.

This Nannie Slagg is an order of magnitude better than her BBC-miniseries predecessor, who wasn’t just hapless, but also superior and unlikable. That portrayal didn’t feel quite fair to the character, who has enough issues without really emphasizing her sense of class distinction. Due to dramatic irony, it’s quite funny that this Slagg worries Steerpike won’t remember Lord Groan’s message in order to deliver it to Cora and Clarice. After all, how should she know that Prune’s new assistant is Steerpike, hypercompetent sociopathic murders-teen? But she doesn’t remain ignorant of what she’s dealing with long. This adaptation has Fuchsia’s nurse smell a rat and cotton on to Steerpike’s plan to shag his way to power via her charge. Sibley’s found a legitimate and pressing reason for Steerpike to kill her, and so this aspect of the play works a bit better than it did in the ‘84. Again, it’s odd that everyone adapting the piece decides to take this line—ninety-nine murders but Nannie Slagg ain't one. Providing Steerpike with more motive here does solve a common problem for adaptations, though really it’s one they’ve created for themselves.

Bellgrove is the “recently elected” headmaster in this version. I can understand deciding to simply skip his ascension, which is due to his predecessor having gone flying out the window. By the time the previous headmaster’s assistant elects to defenestrate himself due to the embarrassment of the situation, it’s all become a lot to deal with. This Bellgrove sounds a touch like Stephen Fry, which is fair because that wasn’t a bad casting choice in the miniseries. Honestly the role Stephen Fry plays in British intellectual life (nice with some pretensions to authority but not trying very hard and ultimately a bit useless) is Peak(e) Bellgrove, so the associations harmonise nicely. There are always losses and gains by the radical cuts an adaptation like this demands. One misses the Brown Hermit, the Tom Bomba-nil of this production; one does not miss Hour 5 of the Swelter vs Flay Literal Thunderdome.

As in several adaptations, Prunesquallor emerges as an unexpected key figure in this text, working something like Tom Pinch does in Martin Chuzzlewit. The adaptations have, I think, done me a favour in making me see how much work Dr Prune does in the plot, and how centrally the story’s morality is with him. This adaptation makes Prune especially queer-coded and camp (“or rather, you tantalize me—in a pleasant sort of way” indeed). He’s also awkward, with a real Amadeus of a laugh, funny (“Steerpike, of the many problems”), and fundamentally a decent person. We first realise this roughly when it feels like Peake and the book itself do—when Steerpike tries to flatter the Doctor by speaking of his ambition, and Prune flatly doesn’t go for it. Prune can be the only character who feels like he’s from our world, The Only Sane One In The Room. He might even know our references: his “gown of darkness is good” line seems lifted straight from Polonius’s “mobled queen is good.”

Prune is more intelligent than his antic demeanour might suggest, and is onto Steerpike’s “amusing fascination with toxicology” from quite early on. In fact I occasionally thought the adaptation made this point too directly, allowing Prune to know it’s Steerpike killing people to a degree he shouldn’t that early in the narrative. Still, Sibley did well selling why Prune might buy Steerpike’s account of Barquentine’s assassination here, and Alfred’s interaction with his deliciously unbearable sister Irma is particularly good in this rendition. His horrified reactions to her Extra approach to dating are thoroughly entertaining (his weird little laugh when she forces him to discuss, or indeed even contemplate, her “bosom”!). The way he’ll nonetheless try to cover for her embarrassing ass when he has to is very sweet.

Titus of course sucks ridiculously, especially as we have to deal with his Alone incarnation: I hate his solo work. His younger actor especially sounds like the miniseries’ Titus, which Dr Katz believes is because all upper-middle-class british children sound the same as a result of having been forced to sing in ethereal choirs for the BBC (see the miniseries’ theme tune). He has his moments—in a play this About Him, it’d be difficult for even Titus to manage not to. The section where he falls asleep in Flay’s cave is well done, and it’s lovely when he tells Juno about his twelfth birthday celebrations. Sibley’s come up with a good way to retain this non-essential but great portion of the book text while doing some of Alone’s work, creating this relationship and conveying Titus’s longing and sense of exile. Another clever dramatic choice is a new scene where Titus and Steerpike interact. Despite the inherent parallelism of their journeys, they really don’t do enough direct speaking in the books. (The play’s use of “bantam” to describe Titus further links him to the crowing Steerpike, possibly accidentally.)

Otherwise, Titus is sulky and entitled. He moans about not liking being talked to like a child by his elders (well, stop acting like one then?), is generally disagreeable and, perhaps worst from an artistic standpoint, while obsessed with his own past he’s not a particularly insightful commentator on it. When he’s in trouble with the dieselpunk surveillance state he tells Juno he used to be the law. Mate, you wish. That was the whole point of those books? Within this ossified system of ritual even you, the privileged summit of the state, were a powerless figurehead out of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s wet dreams. That’s why you left, do you not remember your own—whatever, Titus.

In the Awakes portion, after extensive wandering Titus finds himself working as an orderly in a psychiatric hospital (with Steerpike, Competent and Reasonable Nurse, For Some Reason). This is the weirdest AU. Imagine Titus being at all good at this kind of thing? It kind of makes sense allegorically but in terms of the character, Titus, who never has his own shit together and who’s always struggling against even mild interpersonal obligations (you don’t dump Juno), would be completely incapable of looking after the sick and the difficult. The play also stresses that at this point in his life Titus is in some kind of funk (I guess it’s hereditary—shout-out to the Death Owl), feeling totally cut off from other people and devoid of empathy—more so even than usual. How are you doing this job with none of that? Again: whatever, Titus.

This play manages to make the better portions of Alone quite interesting. Muzzlehatch is good, emitting a delightful laugh when Juno figures out where they are and brings them food. Muzzlehatch is also dead right when he suggests to romantically restless Titus that Juno’s too good for either of them and that they both suck for not appreciating her enough, though for the record I’d prefer to hang out with Muzzlehatch any day (preferably while he still has a zoo—though narrative foresight might make that really sad actually, so never mind, I take it back). What little we see of Anchor is similarly endearing—I could have done with more Anchor. I guess that’s a problem with the book, too: Anchor’s away.

It’s decidedly odd that this adaptation cuts the Underground sequence of Titus Alone, which is arguably the novel’s centrepiece. But then since Alone is almost never undertaken by adaptors and is more lightly academically worked than the previous books, perhaps there’s not much consensus on what the meat of this novel is. Cheetah was of course the creepiest creep to creep creepily, and she needed a goddamn job to occupy her ferretty brain, but again: that’s the text. She did suffer from not having the POV narration she did in the book, and the play didn’t compensate enough for that shift. The creepy robots stalking Titus were likewise successfully creepy. I mean, what do you want, it’s Titus Alone. Barring a full stand-alone David Lynchian treatment which takes both risks and this book on its own terms, and only evokes the lost or fled paradise while delving into this surreal picaresque, you’re not going to get better.

Television

The Web, a 1987 animated short directed by Joan Ashworth

This brief animated film focuses exclusively on the murderous antipathy between Flay and Swelter. It is not suitable for arachnophobes. Spiders are everywhere: eating away at the insides of eggshells, scuttling over walls and beds and bodies, in food, and even amusingly turning the pages of Sepulchrave's book.

This is a commendable realisation of the castle, with niches crammed with masses of candles that look like they've been dripping for decades. I would only take exception to how small everything looks and feels, but perhaps that’s what Ashworth wants—an edge of claustrophobia. One lantern particularly struck me, because it was very like another featured in the BBC miniseries. I wonder if that design team was nodding to this award-winning short?

Dr Katz said it reminded her of both the music video for Phil Collins's "Land of Confusion" and unnerving "apple people" crafts. This film's aesthetic is undoubtedly unsettling, even as it lends itself to comic moments, such as when a chicken keeps walking around after Swelter's cut its head off. Flay's ears twitch in a neat way, but Swelter's thick, lolling tongue turns my stomach. People’s bodies are gross and massy (though to be fair, perhaps less gross and massy than Peake's description of Swelter).

In this version of their fight, after Flay attempts to wrap his legs in bandages to silence his creaky joints, Swelter tricks him into exposing himself. Flay attempts to kill Swelter before the other man can kill him, but what he strikes is actually a giant salt-dough replica of the other man that passed for him in dim light. This is great because we did see Swelter making this hideous double, but neither Dr Katz nor I quite understood what had happened until Flay did. This reverses the element of surprise from the book’s version of this fight, but I thought it simplified the action and removed Flay's advantage in an easier to understand and more compelling way than the BBC miniseries did when it similarly shifted the dynamics of this contest.

Ashworth’s story isn't that fair to Sepulchrave, who warbles fearfully in his bed, tries to fling himself out the window whenever Flay's back is turned, and blithely, cluelessly, plays piano during his servants' fatal contest. But then this adaptation isn't about him, and that shift of focus is perfectly legitimate. It’s surprising and narratively satisfying when, after Flay fails to catch him and keep him confined, Sepulchrave actually grows wings and flies out the castle window.

Joan Ashworth has accomplished a lot here without dialogue, using only a single title card to set up her plot. Her canny selection of a subject enables her to do justice to her narrower range of material. Simultaneously, she makes some sensible changes that clarify and strengthen her chosen plot line, and takes an especially bold departure with the ending. Ashworth finds a Gormenghast staging that works for her medium and purposes. She's used the text effectively to create a cogent independent artwork.

Before we discuss the major BBC adaptation, I’d like to point out that I have not seen the BBC’s related short film A Boy in Darkness because it’s nowhere online. Again, if the BBC can find any way to be careless of its own posterity, it will gleefully exploit it. This, from Wikipedia, is literally all I know about it:

Also made in 2000, the 30-minute TV short film A Boy In Darkness (adapted from Peake's novella Boy in Darkness) was the first production from the BBC Drama Lab. It was set in a “virtual” computer-generated world created by young computer game designers, and starred Jack Ryder as “The Boy” (a teenage Titus Groan), with Terry Jones narrating.

Wacky.

GORMENGHAST: THIRST TRAP. The 2000 miniseries directed by Andy Wilson and written by Malcolm McKay for the BBC.

Was it kind or moral for Dr Katz, Dr Aishwarya Subramanian and I to trick Samira Nadkarni (henceforth Molly, Aisha, Samira) into watching the Gormenghast BBC miniseries when we’d all read the books and she had no idea what she was getting into? Of course it wasn’t. But it was an very informative experiment, and it was funny. (Besides, she subsequently made us all watch a film entitled Albion: The Enchanted Stallion, so she got a bit of her own back, trust.)

From the chatlog: “Samira: Fair warning: I know nothing about the books or this adaptation. All I know is I am promised melodramatic BBC.”

Come, reader. Come with poor Samira on a terrible journey.

This adaptation features sequences and design elements I love, and yet ultimately it’s the telling that makes me angriest. The miniseries makes the least defensible decisions: if there needs to be one, it’s The Worst Version. I suppose I’m grateful that there’s a full filmed Gormenghast, but I only have to remember the miniseries’ worst sins to get so angry that I realise I must like these stupid books after all. Please stop violating my amoral and ugly son, who is only trying to have a barbecue—

(Of course this is available online; it has Jonathan Rhys Meyers in it. Of course it should be accessible in this fashion, since it’s very difficult to buy at any reasonable price and restricting access to it does no one any real good.)

The miniseries’ opening theme pretty much lets you know what you’re in for. A bird flies about. It is Mr Chalk, the white raven, but Samira thought it was some sort of chicken or seagull. (I developed a revolutionary Heated Take regarding the events of this opening of which I believe you should all be aware: Mr Chalk has Titus’s violet eyes in this version. Is he the real father?! Gertrude definitely spends more time with him—) She was particularly horrified by the theme tune, sung by a piercing boy falsetto who gives us one of the Master of Ritual’s canonical incantations as a kind of hymn. Aisha observed that “a certain section of fantasy adaptations just think shrill children are Ethereal.” Personally it worked okay for me, but I alone was not offended by what Molly called the Shrilldren of the Stonelanes.

Christopher Lee tackles the monosyllabic role of Flay with commitment, giving us a wonderfully bizarre “Drop, boy!!” in one of his initial scenes. (“Boy” in question being Steerpike, or “Queerpike?” to a not-very-interested Flay.) (Samira bonded with him early, in that very kitchen scene, when faced with Swelter’s drunken forcible sing-along and the pet name “my ray of addled sunshine”: “That man staring in horror is me. I am that man.” I felt more connected to the terrified-looking kitchen boys. “These children look how I feel.” “Vaguely Dickensian?” Aisha asked, extremely rudely.)

I generally get on with the series’ production choices better than its overall narrative thrust. As Aisha observed, “given how big the books are, it's an incredibly faithful adaptation.” They’ve kept a lot of small, telling, or interestingly queer details, like Fuchsia’s having already taken a bite out of a pear that the desperate Steerpike then finds in her attic and finishes. The miniseries’ scenes, however, cram in too much information, and the transitions between them happen far too quickly. This is especially a problem early on, which is the worst time for it. The story is intelligible if you know the books, but as Samira and my partner Katy both observed, the first episode in particular can be difficult to follow and off-putting if one doesn’t. Samira found our insufficiently explicated first glimpse of the ceremony of the Bright Carvers particularly baffling. The arc of Lord Groan’s descent into madness, the escalation of the antagonism between Flay and Swelter, the demise of the twins, and several other plot elements simply were not communicated with sufficient clarity. Perhaps at this juncture the production valued representation (as with those preserved details) over bringing in new viewers and establishing itself on its own merits.

Aesthetically, the miniseries is hit and miss. The music—when Steerpike and Fuchsia meet (and he does a temporally improbable Groucho Marx impression), at Irma’s party and elsewhere—works rather too hard. It is not the handiwork of Murray Gold, but it really feels like it is. The CGI is as painful as knowing this came out in 2000 would lead you to expect. Some early productions to employ CGI, like Great Mouse Detective, had the sense to use the fledgling technology sparingly and elegantly. But this was not common sense, and it is not in evidence here. The early shot of Steerpike looking through a keyhole, however, is superbly sinister. (Aisha) A lingering shot of the ivy on the castle walls in an early episode elegantly prepares the way for the final battle, which takes place in that ivy.

This production makes an unusual, almost theatrical choice to shift elements of the show’s time period as the story progresses. I could see an adaptation with several of these stagecraft elements playing well at the National Theatre. [3] We see some of Gormenghast’s guards sporting what look like Great War-era helmets, which are jarring against this medieval or Early Modern background (which also contains elements of Victoriana or Edwardiana: Irma, Alfred, the school). When Steerpike becomes Master of Ritual, his part of the castle shifts to a World War II or even Cold War-inflected aesthetic Samira called “pomo accounting.”

This transformation suggests mechanisation, Steerpike’s antiseptic calculation and the change he could bring to this world. And yet I wonder whether this visual break risks suggesting too great a transformative vision on his part? Steerpike largely operates within bureaucracy, or at least under the cover of it, rather than contesting it and instituting new ideas. He’s not a Movement person. “All the cash—all the fame! (And social change ... ) Anarchy—that I run!” Steerpike’s mask (oh, we’ll get to why he wears a mask after he’s injured in this sodding adaptation—) also has a touch of World War II about it, though it’s chiefly reminiscent of the Phantom of the Opera (or the Genghis Khan video—).

Aisha mentioned Anthony Burgess’s theory that “Gormenghast” is a clever anagram for “German Ghost,” but we weren’t really feeling it. While the third book is absolutely World War II inflected, to declare the first two books Really About a specific allegorical relationship would constrain their conceptual range unduly. The particular interaction of text and historical situation Burgess proposes is only limitedly provocative and generative. While I’m intrigued by the miniseries’ design concept, I’m not sure how much it ultimately speaks, beyond looking a bit neat (and potentially: being a bit confusing). I could have gone with more here, perhaps: more oddity, more medieval lushness, more decay, more radical juxtapositions and shifts.

Perhaps as a consequence of staging this story and trying to make it play theatrically, and of the BBC’s association with heritage adaptations and the placement of this miniseries within that canonical tradition, this production leans into Peake’s text’s Shakespeare associations. This Titus is in many ways a sort of equally stymied anti-Hamlet who wants to strike out from the castle of his (arguably) murdered father (who he eventually, almost accidentally avenges), complete with a mother called Gertrude and incest-tension, here shifted onto his two sister-figures. Peake’s composition period was also the height of the popularity of Freudian readings of the delay in Hamlet. Fuchsia and Sepulchrave, meanwhile, play out a miniature Lear. Based on this adaptation’s particular enunciation of these qualities, I could see an argument that Shakespeare is the literary interlocutor Peake’s mostly addressing himself to. Personally, I ultimately think Peake’s relating most strongly to the Victorian novel, and that he happens to incorporate its antecedents and fixations in the process, namely the gothic, the picaresque, Shakespeare, and the Romance.

Molly felt, and I would agree, that the creative team “didn't trust Peake enough, maybe. I think that's one of the things Shakespeare directors also have to be really careful of—not quite trusting the text enough.” I do think the medium shift makes it very difficult to convey a lot of the books’ character introspection—something Shakespeare would have accomplished with asides and monologues, technical resources which no Gormenghast adaptation yet has had anything like the balls to play with (as it were). These in part self-imposed limitations render Titus and Fuchsia particularly challenging to realise meaningfully.

The (book) series’ mood is perhaps its defining characteristic (or range thereof—its palate of moods? The keynotes of that palate? Its aesthetic?). It’s difficult for me to think of other major Western literary works of which that’s true. A key burden for adaptations is thus to productively engage with this representational task. However Molly observed that “this BBC adaptation hasn't given us enough quiet time with any of the characters. I'd like some more time just with Fuchsia, or Steerpike, or Prunesquallor. There's always something assailing you.” Oddity and bafflement are certainly affective energies of the source text, and while I find it refreshing the miniseries seems interested in purposefully cultivating them,[4] that cultivation does come at the expense of our connections with characters in a way it doesn’t for Peake. We know this place is strange; we’re not allowed to inhabit its strangeness. Largely, especially early on, we’re just bombasted with Gormenghast.