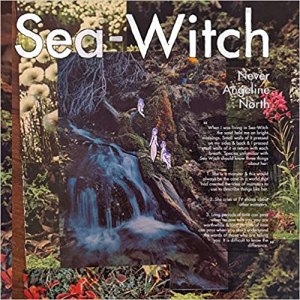

Sea-Witch is a four-hundred-page omnibus of a chapbook-zine series of the same name that reads like an offline print-out of a social media side account. Specifically, the kind of locked alt that half-wants to be found, and in its self-conscious wanting for discovery, is also perpetually clarifying and/or destroying its rawest expressions. This seems like an extremely cool and sort of inevitable way for independent art and writing to present itself circa 202X.

Sea-Witch is a four-hundred-page omnibus of a chapbook-zine series of the same name that reads like an offline print-out of a social media side account. Specifically, the kind of locked alt that half-wants to be found, and in its self-conscious wanting for discovery, is also perpetually clarifying and/or destroying its rawest expressions. This seems like an extremely cool and sort of inevitable way for independent art and writing to present itself circa 202X.

Sea-Witch is about witches, kind of, and “gender,” kind of (what I personally recognize as that mix of authority, resentment, insight, and impatience with all the ways one’s identity inevitably shapes the reception of one’s art). It’s also about sadcore e-girl apocalyptic goddess worship, music, and dogs (that are witches). It’s also about death drives and soft-focus Pacific Northwest woodlands, occult sigils, and a pulsating desire to be known that is locked in some hellish orbit with a petrifying fear of the same.

Sea-Witch takes the punk rock pleasure of a gossip burn book and applies it to the reverent wonder of a fantasy bestiary where all of the animals are loose fragments and amalgamations of a trans woman, her/their iterative selves, lovers, oppressors, friends, traumas, dreams, nipples, assholes, and tattoos. Precise distinctions blur, and roles are refused before they can ever solidify into something as compromising as expectations. Each page of vignettes, poetry, photos, drawings, and MS Paint-style annotations, redactions, and meta-commentary operates like an infinite scroll, a scream-stream of consciousness in a sequence of panels in an art book, which is also anti-art and anti-book when either construct fails to serve its purpose.

And all constructs are constantly under suspicion: the book encourages you not only to steal it but to generally pirate and shoplift books under the slogan of “Fuck capitalism” (p. i). It offers its dedication to “all monsters” and “fuck the police” right before it checks in with a clinical list of PTSD trigger warnings[1] and an “18+ only” label due to the interspersed inclusion of (mostly softcore) nudes. So, part of me is skeptical of what mindset I am expected to bring to reading Sea-Witch: that I should pilfer the DSM-5 from my local bookstore? That I might defy the most arbitrary and violent institutions while ensuring a teenager doesn’t see art photography of an anus due to the legal liability?

Just the same, this whiplash of directives is an accurate preparation for what’s to come. In one script-shaped scene, a character asks her lover, “Like does a story have to have an order or some sort of overall arc or can it just be a lot of things that happened? What if plot is fake?” (p. 200). These characters then decide to multiply across a set of parallel worlds, so that one pair in one world can have sex and the other pair in their other world can read in bed and fall asleep.

Throughout Sea-Witch, things and people and events are and also aren’t, and, importantly, are only these polar extremes and never just somewhere in the middle or merely in between. Sea-Witch asks you to see contrasts without compromise, engage in questions and answers that do not resolve, and inhabit bodies that are irreconcilable with embodiment.

Fundamentally, Sea-Witch is a work that is at odds with itself, formally and thematically. A set of paintings with text in them leads to a painting of the word “[MISSING]” followed by plain text of the file name for an image followed by a solid static field of the letter P (pp. 304-314). “I am not here to talk about my body” (p. 5) one version of the narrator warns us, amidst an enormous number of quotations throughout the omnibus from other books, posts, and sources that are very much about the personal body. That narrator elaborates: “I wish I had another way to tell this, but for now I will speak of the events & occasionally will do so through my body, though I want you to understand that my body is not the focus. My body is not available for consumption.” This felt, to me, like as much of a refusal of lurid gazes as a manifesto from the corpus of the text itself: look at me, don’t look at me, and please look closer, and fuck you for looking.

Sea-Witch is also both fantasy fiction and religious testament. Even when the effect is surreal or dreamy, it does not quite become surreal dream logic, because it does operate with an enormous amount of internal consistency and self-reference. This is a kind of logic that can be found in both fairy tales and theological study, where understanding may simply be outside your typical suspension of disbelief. The slippery times and places and causalities in myth-making can amplify and extend points of view that are misfit and marginalized (a feature that surely accounts, at least somewhat, for the proliferation of contemporary misfit and marginalized writing that adopts a fabulist voice). A “flatness” in tone and an opacity of intentions can assert a refusal to perform the elaborate and exhausting work of making one’s characters[2] relatable (A.K.A. likeable[3]) to the reader, and instead demands that the reader either meets the story on its own terms and accept that they may touch something they cannot possess, or, you know, buzz off.

This works to incredible effect in Sea-Witch, particularly through the recurring motif of monsters and monstrosity, and some of the strongest textual moments in the book are the meditations on otherness and transformation. “Only a monster in her Sara phase could have written a book such as this one,” reflects one version of the narrator, before issuing a perfect example of this type of blunt invitation either to take her at her word/world or leave her alone. “As I am always in the process of formation, it is possible that by the time you read this you & I will no longer be mutually intelligible. It is also possible that this is already the case” (p. 84).

Occasionally, the mysticism and allusion come apart at the seams a bit, too, and the cloudier references to placeless pain and tears don’t always achieve the significance or heightened impact they may mean to. But this is, of course, assuming they mean to. And who am I, the Authorial Intentions Detective? Recall that: fuck the police. There are no mid-ranges here, so one reader’s uncontrolled queer stoner chaos will be another’s maximalist—quite thorough, quite serious, and revelatory—spiritual investigation of (gendered) self-destruction as an intrinsic twin of self-creation. The book’s funniest, sexiest, prettiest, and scariest parts are the ones that churn forward several moves ahead of the reader’s preconceptions, so while saying a piece of literature “defies categorization” is usually review-speak for “I’m not sure I know what I just read,” Sea-Witch seizes on this defiance as the essential pleasure among its many qualities.

[1] I have mixed feelings about content and trigger warnings when they are author-provided, which you can read here if you’re unsure of my meaning in bringing them up at all, but I don’t want to derail this review.

[2] Commonly assumed to be oneself.

[3] A.K.A. loveable.