(Previous)

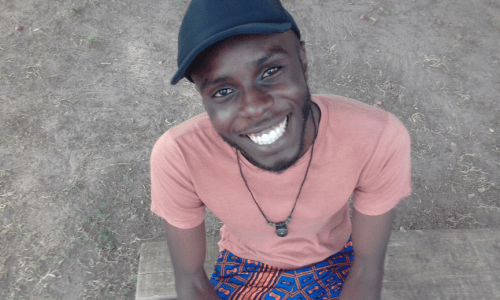

TJ Benson

The desert land was disturbingly calm, a picturesque scene of tea-colored sand dunes undulating gracefully into the horizon against the backdrop of a still, azure sky. Only a small settlement fenced by brick walls disfigured the otherwise, unspotted land. It was a survivor camp and in it, all was well. Children danced round narrow alleys and passages, adults went about the miniature streets, performing the tasks that the marshals had assigned them. Asides that, everything seemed stiff, like still-life painting. Even clouds seemed suspended tuffs of wool. Then, as though to prove the desert’s credibility, a whirlwind started in a bee-line towards the settlement.

It had emerged from the horizon, first like ribbons of smoke in the air, then huge spinning waves of sand, dancing hypnotically toward their settlement with a low hum. No one exchanged a word; they all knew what to do. The adults gathered the little ones and sucked themselves into the nearest shelter.

Only one man seemed unaffected by the impending sandstorm. He just sat at the entrance of his shelter, a shade made of four bamboo sticks and thatched roof in a yoga position, with his eyes closed. He was a young brown-skinned man, somewhere around 25 years of age. No one bothered about age in Oblivia. He wore a faded blue, loosely fitted kaftan and a locket about his neck.

Rachel had always been aquiver with curiosity every time she passed his shed. Sometimes she would catch him rub the locket reverently in between his thumb and forefinger. He was doing so now, but she wasn’t in the mood to ask questions, she had come for shelter

“How can you be out here, can’t you see a sandstorm coming?” she queried, rousing him out of his meditation. But of course, he wasn’t offended. She had never seen him offended.

“Is that why everyone is running?” he asked incredulously. “Because of a sandstorm?”

“Unlike you,” Rachel said, “people actually value their lives.”

“Really, and what is life?” he asked.

“Please let’s go inside. You heard our marshals the last time they talked to us, disasters happen. But we are responsible for our lives. That is how we escaped the Armageddon in the first place!”

The air was already filled with sand. Her hair thrashed about her face like the sails of a ship wrestling a storm.

He shook his head. “Things happen, but it is we that choose how to react to them.”

“You will get us killed!” She shrilled, turning to look at the advancing wind. Her heavily lashed eyes narrowed in fear as the wall of sand swallowed the entrance gates.

He smiled. “Just put your hands in mine.”

“This is not the time to ply your trade!”

He stretched out his hand to her. There was an urgency in the gesture that belied his calm demeanour. “Do it now!”

She had the extra second to take refuge in the inner room, but something in his eyes willed her. She was compelled to take his hand, no matter what dangers lay ahead. His kaftan billowed about his brown skin and her hair danced in the air as the wall of sand drew closer.

Just as the wall was about to swallow them, she felt the warmth of his hand envelop hers and the impossible happened: the sandstorm disappeared.

From ‘Oblivia’ in Jalada

I met TJ Benson at Ake 2017 and everybody said I had to interview him. A few months later, the publication of a single-author collection of his stories was announced. So he has joined Ayodele Arigbabu, Dilman Dila, Helen Oyeyemi, Irenosen Okojie, Lauren Beukes, and Lesley Nneka Arimah as a spec fic writer with their own anthology. He’s also one of the few African writers I met who focuses on putting the future into Afrofuturism.

I told him that I was interviewing him because everybody said he was a great writer.

TJ: (Chuckles, embarrassed) “Yeah. I hope they’re right. I dwell mostly in fiction. I am more interested in actual human experiences, so even when I write sci-fi it’s a little easier for me, because there’s a lot of complicated sci-fi stuff that’s tough to read so I try to avoid that. It’s easy for me, even in the future, even in an alternative universe, to have actual human beings dealing with human stuff.

“I’m more into short stories. My first short story was published in Sentinel Nigeria Magazine and my first sci-fi story published in Jalada 02. That was ‘Oblivia.’ And my collection of African sci-fi, all sci-fi, was shortlisted for the Saraba Manuscript Prize. It’s going to be published by Parrésia.

“‘Oblivia’ is actually a chapter in what is intended to be a novel. It’s about people being abducted by creatures in their mind. We all think of aliens as coming from outer space, but I saw them as something we create in our minds when we think about them—imagining them makes them real. A lot of the population of the world goes to sleep one day, and there are consequences and stuff. I had issues with consistency as a novel, so I just left it as a short story.

“My collection of stories, We Won’t Fade into Darkness for Saraba, I did it because I was trying to imagine where Nigeria would be in the next hundred to hundred and fifty years. It seemed that nobody was thinking that far. People were focused on the materialism of now. It was terrifying what I saw. Because of collapsing aspects of life in some of our communities, I saw them as potential breeding grounds for horrors to come. But not all of it was dystopic. I saw some beautiful things that could happen. So I decided to dream.

“I also had an alternative universe story. I had the story ‘Passion Fruit’ asking, if British colonialists didn’t leave the country and were still in control of the country, what Nigeria would look like.

“A short story of mine, ‘An Abundance of Yellow Papers,’ won the AMAB-HFB Flash Fiction Competition for 2015. It’s online and you could read it.”

Other online fiction from TJ includes “Waiting for Beauty” in the Munyori Literary Journal. In 2016, Brittle Paper published “The Spirit and the Chi.”

TJ: “I deal with issues at hand, and some of these issues I find that alternative universes or futuristic versions of life from now are the best ways for me to treat them. I’m not fixed in science fiction; I’ve just written quite a number of science fiction stories.

“I was on the shortlist for the Short Story Day Africa Prize this year, and the winner was Sibongile Fisher with a piece of speculative fiction.”

There is an online version of his story, “Tea,” published as part of the 2017 Short Story Day Africa anthology, Migrations.

Short Story Day Africa is a yearly competition and anthology. A key figure in the programme, Rachel Zadok, explains how it works in an earlier interview in this series. The 2017 competition was on the theme of Migrations. The speculative stories included in the anthology are listed in Wole Talabi’s database on the ASFS website:

-Anne Moraa

-Blaize Kaye Diaspora

-Mary Ononokpono

-Nyarsipi Odeph My Sister’s

-Sibilonge Fisher A Door

-Stacy Hardy Involution

The shortlist is created by readers all over Africa, reading the stories blind without the author’s names, then read by a panel. Migrations, the 2017 SSDA anthology is available on some Amazons, but not all (yes in the USA, no in the UK for example). In 2014, the SSDA anthology was devoted to speculative fiction.

TJ: “I was really excited. It seems there’s an emergence. I realize that speculative fiction and sci-fi are not necessarily that recent because I’ve read some of my father’s anthologies of African fiction from the ‘60s. What we call magic realism could be our science fiction because of our juju technologies and all of that (Laughs).

“Sci-fi for me is not just about technology. It’s springing from our actual culture, springing from our traditional practices, our spiritual experiences. I always think of how I’m able to call London by smartphone. One hundred years ago that could be called witchcraft.

“Because of what we are going through, we are trying to imagine life better and invent futures for our descendants. We’ve been stuck in circles, if I can use Nigeria as a context. I remember reading and realizing the first election ever held in this country was rigged. Many people of my generation who don’t know our history think that this whole rigging of elections is new, a new development. But a lot of things we are dealing with now have been in existence for a long time.

“I think we have lots of alternative fiction writers coming up now as a kind of reaction to the repetitive cycle of lying, corruption, and degradation of society. We have to start to reimagine how things might work so that our children, or future generations, will not be stuck in what we are experiencing now. I think personally now, 2017, we had a lot of artists coming out in all fields, including literature.”

I mishear TJ say 2007 and so we talk about the last decade’s history of SFF—Chimurenga and Jungle Jim and the rise of Omenana. We talk about how hard it is to get hard copies of books and how Amazon doesn’t work in Africa. We begin to talk about Jalada and pan-Africanism.

TJ: “The pan-African thing—when I first heard the word I got very excited. I thought, ‘OK, yes, I’m connected to other Africans. I’m going to get other sides of it.’

“We are still, shall I say tribalistic now? Insular. We are still fixed in ourselves. ‘Oh, those Kenyans, they are this way, oh, those Nigerians are this way.’ We are still treating each other as the Other. You get to experience this in airports where we are travelling between African countries. Nigeria to Kenya, trying to get visas. Or in the intercontinental wars of Twitter.

“I have been able to work with artists from other countries. This year I taught a creative writing workshop for three weeks online. For the last week I was able to get three fantastic authors from Kenya, one from South Africa, one from Namibia, and one from Cameroon. It was lovely—it was hopeful of the pan-African ideal. We all had similar issues, since Kenya and Nigeria are like sisters and we’re trying to think of how to reshape our collective futures.

“The opening story ‘Pretty Bird’ of Transitions [Saraba Magazine’s first print publication] that will be launched tomorrow [at the Ake Festival] is about a girl who used to be Ghanaian. She meets this guy who used to be Nigerian. I say, ‘used to be’ because at this point, because of a war with machines, boundaries have ceased. Nobody knows who is operating these machines that turned on everyone. He comes in and he suggests they start a life together, but she has paranoia issues because she finds him using the digital tech.”

The launch party for the Transitions anthology at the 2017 Festival (photo courtesy of Ake Festival).

Saraba Magazine was started by Emmanuel Iduma and Dami Ajayi in 2009. It’s a primarily online magazine. The influence of Saraba Magazine is long-term and complex, as is its relationship to SFF.

TJ: “Saraba picked a story out of my anthology for the Transitions issue. They picked ‘Pretty Bird.’ Parrésia didn’t mind because Saraba are kind of like my agents, and they are the ones who got Parrésia for me. They represent me with Parrésia.”

Ikechukwu had briefed me earlier that TJ was writing a novel. So when I ask TJ about it, he erupts into laughter, and asks me why I am asking him that.

TJ: “I completed a novel two weeks ago. I’ve been writing it for nine years. It’s called The Madhouse. It’s definitely not sci-fi. But it could be classed as magic realism because of the traumas of my characters. It’s set in the era of the Nigerian military regime, starting in the 1980s, but ending up in 2016. Because of the traumas these people went through you have the rise of the Pentecostal churches in that era. A man and woman try to be together despite their different backgrounds. He escaped the seminary; he realized he didn’t want to be a holy father. She ran away from home because her parents were strictly religious. It has a lot of elements you could interpret as magic. Their first son ate his brother in the womb and the brother comes to haunt him. It’s kind of the crux of the story.

“I have lots of stories online. There’s ‘Oblivia’ in Jalada, ‘Gastronomie’ in Transitions magazine. And I have a story in Bakwa Magazine on mental health, it's titled ‘1985.’”

After TJ mentions his dad, I ask him to tell me a bit more about him.

TJ: (Laughs) “He was really crazy. He was a photography fanatic. He studied fine art in school but he became a site engineer. So he did sculptures for friends, his foreign friends, and he read a lot of books—autobiographies, art, books on writing fiction. We had these huge shelves in our living room (Laughs).

I ask some usual biography questions. TJ studied quantity surveying at uni, so now works in the construction business like his dad—he works for a company that gives him surveying only when there is work. I ask what books he read when he was a kid.

TJ: “Enid Blyton, although my mum bought those for me as children’s books. She said, ‘Stay indoors, I don’t want you outside playing ball,’ because I was always outside playing football. So she got me those book series—The Famous Five?

“I do creative photography, so [I should mention] my dad’s books on photography. There’s this anthology of Sunmi Smart-Cole, a book of his photography with a foreword by Wole Soyinka. That sort of gave me an idea of what I wanted to do with creative photography.”

TJ works also as a professional photographer. Brittle Paper posted about the work available on his Instagram account. TJ was Brittle Paper’s official photographer for the Ake Festival that year.

One of TJ’s photographs.

TJ: “I also watched a lot of TV. (Laughs) I still would, but I write a lot now so I don’t have time to get to watch stuff. But [I watched] Voltron, The Little Prince, the Power Rangers—I can recite all the moves. (Laughs) I am becoming a child again.”

Ikechukwu, who was present for our conversation, turns to TJ and asks if he grew up in Lagos.

TJ: “No, Abuja.”

Ikechukwu: “So you wouldn’t be familiar with Battle of the Planets and Terrahawks?”

TJ: “No, no.”

I say that Abuja, the city, is pleasant but a bit dull.

TJ: “Dull. But I like dull because I get to write and there’s space in my head to think. [Goes back to listing childhood favourites] Dexter’s Laboratory—it was a cartoon, it was good. Samurai Jack—there’s a dark streak in most of my writing, especially when I’m writing sci-fi. It came from Samurai Jack—the inevitability of fate. He had to keep on travelling through time to fight this Aku monster. It hit me, the inevitability of fate—that can’t be changed. Lots of sci-fi, they trying to alter time to remedy events, but I found, I don’t know …

“I read lots of comics, X-Men, Marvel, I loved them. I got hold of them from my dad. I was always travelling with him. He was a site engineer. Just inside Nigeria. He might have a meeting in Jos so we would go and come back.

“He would always get me a comic to keep myself busy in the car. I don’t know how Nigeria had such access to magazines. He read his Ebony magazine, the black magazine. He had stacks of them. He had lots of friends in the US, so they were always sending them to him. And then when his son started reading comics, he told his friends (Laughs) and they started sending those too.

“I grew older, and when I got to JSS 1-2 [a junior school level] I encountered Harry Potter, which was perfect for me because by then both my parents had died and I could relate to the whole seeming to be struck by fate for something. So Harry Potter had a very strong influence. And I started getting in touch with horror, Fear Street, R. L. Stine.

“I was between eight and ten when my parents died. I started living place to place with relatives; that was when I became an avid book reader. Before that I had to be forced to read, but after that I had to hide in books. I enjoyed stories, but as of that point I had to live inside them. And I started writing when I exhausted the stories. I started reading newspapers, prescription bottles, anything not to deal with human beings (Laughs). When I exhausted stories I had to start creating them. So … (falls silent for a bit).

“He was very crazy. I don’t know where he got that from. Yah! He was good crazy. He read a lot and he put a lot of … he gave me my first camera when I was nine years old and from where I was coming from, that was a big deal. His friends were like, ‘Why would he give a child a camera?’ So he kind of took me seriously in the sense that that was not what his peers were doing. He was what people call crazy in that sense.”

(Next)