Mary Fan

“Where words fail, music speaks.” The famous quote attributed to Hans Christian Andersen has become one of those adages so common, it’s easy to forget it even has an author. There’s something profoundly evocative about certain combinations of pitches. How many times have we seen versions of that meme “You can’t hear a picture” featuring a movie still that’s indelibly attached to a powerful sound effect or melody?

We use music to tell stories, to express emotions we can’t find the words for, to change our moods and the moods of others. So, of course, in sci-fi/fantasy, music plays a role in creating the fictional worlds we’re to be immersed in. It’s so entwined with our lives that to not mention it, at least in passing, would seem to be an omission. Star Wars includes space bands (playing a style of music unfortunately named “jizz” that’s both derived from and rebels against contemporary styles). Star Trek gives us Klingon opera, among other things, and even used music as a major plot device in Star Trek: Discovery. Lord of the Rings includes countless songs that reveal characteristics of its fantasy cultures. Even stories that don’t feature music so prominently will usually at least have a character mention a favorite song.

This is all music that’s part of the sci-fi/fantasy world, music that the characters can hear (in academic speak, diegetic music, as opposed to the non-diegetic soundtrack that sets the tone or heightens emotions for the audience but isn’t heard by the characters). Film and TV have the advantage of showing the audience what their world’s music sounds like. But what about for books, a medium that is, by its nature, silent?

Music as Storytelling

Composers, songwriters, and performers use music, whether it has words or not, to tell a story. Each note is a letter, and each combination—a scale or a chord, for instance—a word that builds into a phrase. Melodies are sentences, growing into sections like paragraphs. For longer pieces, each movement is a chapter, building up to the final conclusion. These conclusions are often expected—that final big chord that your ear just knows is coming. But they can also be deceptive—a buildup that trails off into nothingness, or lands on a note that feels wrong. Forms and conventions are observed or intentionally, pointedly broken, as it is with tropes and archetypes in fiction.

Those who write about music or incorporate musicality in their words often have an innate sense of that, whether or not they’re able to describe it in academic terms. And with this sense, writers often, possibly unknowingly, incorporate a few techniques from composition and songwriting into their prose.

Storytelling as Music

Let me begin this section with a disclaimer: Everything I’m about to write is from the perspective of one who grew up in the US, speaking American English, learning from the Western canon. Music is, of course, specific to individual cultures, and what might sound melodic to one might be considered cacophonous in another. The examples that follow only apply to my particular American-educated, English-speaking perspective.

Words have an inherent rhythm and musicality in themselves, which writers can employ to create a soundtrack in their reader’s head. The term many will remember from grade-school English class is onomatopoeia: a word that sounds like the noise it describes. The zap of a phaser. The hiss of a steam engine. The pitter-patter of children at a magic school.

And then there’s the more obscure phonestheme: a pattern of sounds systematically paired with a certain meaning in a language, which can be literal or figurative. For instance, the sl sound is associated with the lack of friction, both physically (e.g., slippery, slick, slide, sled, slime), or metaphorically (e.g., slut, sly, slug, all associated with a lack of old-fashioned morals). Is it any surprise, then, that J. K. Rowling chose the name Slytherin for the Hogwarts house she wanted readers to think of as villainous?

The gl sound, meanwhile, is associated physically with light (think glitter, glimmer, glint, glow, and, one of my personal favorites, glisk). From there we get less literal words like glare, glance, and glass, all associated with the idea of light sparkling off something. And how about the good witch Glinda in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz?

The gl sound, meanwhile, is associated physically with light (think glitter, glimmer, glint, glow, and, one of my personal favorites, glisk). From there we get less literal words like glare, glance, and glass, all associated with the idea of light sparkling off something. And how about the good witch Glinda in L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz?

In a more obvious and perhaps intentional example, the -ump sound is associated with roundness of objects or piles, such as clump, lump, and rump. Small wonder, then, that Lewis Carroll described the nursery rhyme character Humpty Dumpty as an anthropomorphic egg.

I doubt most sci-fi authors naming their characters and places with made-up words pause and think about which combinations of sounds are associated with what traits. But spend enough time around words, and you start to get a sense of it, and when it comes time to invent a name, certain ones just seem to match more.

Another term you’ll run into when diving into the academic rabbit hole of language is phonaesthetics: the study of beauty and pleasantness associated with the sounds of certain words or parts of words (the term is believed to have been first used by language aficionado J. R. R. Tolkien). In other words, some words just sound pretty. Here are a few: tranquility, serendipity, luminous, gossamer, mellifluous, ethereal.

You’ll probably recognize these as words often used to describe good things in fiction. An ethereal fairy with gossamer wings and a mellifluous voice. A garden of luminous flowers that provides serendipity, or tranquility, to those who wander through. Or they’ll be used ironically—the deceiver with a mellifluous voice, the luminous cavern that lures travelers into danger.

When worldbuilding in sci-fi/fantasy, storytellers want their audiences to feel certain ways about certain characters and places. Calling upon the words considered beautiful is an evocative way to do so.

But what do these words have in common? Take a step further down the academic rabbit hole and you’ll encounter the 1995 paper “Phonaesthetically Speaking” by David Crystal, which explores such criteria. Three or more syllables, usually with stress on the first syllable. L as the most common consonant, followed by M, S, N, R, K, T, and D. Short vowels (e.g., lid, led, lad) rather than long ones and diphthongs (e.g., lied, load, loud). Three or more manners of articulation—meaning you might say one letter with your lips closed, one with the tip of your tongue, and one by biting your lower lip (try staying mellifluous out loud and you’ll see what I mean).

Because of these preferences among English speakers, certain non-English languages are considered more “beautiful” than others. French and Italian, for instance, are usually thought of as lovely, whereas German is often perceived as harsh (I’m speaking very generally here; plenty of people will have entirely different opinions). The former two languages have a lot of “liquid” sounds that fit the criteria in the previous paragraph—all those singsong vowels barely touched by quick consonants—whereas the latter is more consonant heavy.

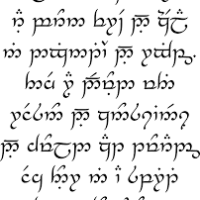

When creating sci-fi/fantasy languages, writers will often draw upon these perceptions to evoke certain characteristics of their fictional civilizations. Tolkien designed the Elvish languages to be melodic and elegant by his standards, reinforcing the idea that these were the most beautiful and sophisticated of his fantasy races (e.g., mae govannen, which means “hello,” or elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo, which means “a star shines on the hour of our meeting”).

When creating sci-fi/fantasy languages, writers will often draw upon these perceptions to evoke certain characteristics of their fictional civilizations. Tolkien designed the Elvish languages to be melodic and elegant by his standards, reinforcing the idea that these were the most beautiful and sophisticated of his fantasy races (e.g., mae govannen, which means “hello,” or elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo, which means “a star shines on the hour of our meeting”).

Contrast that with the Klingon language created for Star Trek by Marc Okrand. The aggressive warrior race needed words that could reinforce these characteristics, and what resulted was a staccato language that practically interrupts itself after each syllable as it forces the speaker to spit its consonants (e.g., pe’vIl mu’qaDmey, which means “curse well,” or the classic exclamation Qapla’, which means “success”).

All this came to mind when it was my turn to create an alien language for the Starswept trilogy. I wanted the reader to perceive these humanoid telepaths, who are centuries ahead of Earth in terms of both technology and, in some ways, society, as being elevated on certain levels. Intelligent, articulate, graceful. And so I went down the Elvish road, pulling pretty syllables from the air and arranging them rhythmically for positive phrases (e.g., en selár Karovyil dira to mean “you are a beautiful Earthling”—yes, this is a romance). At the same time, our heroine runs into some not-so-nice aliens, so to reinforce the cruelty of the more villainous figures, I borrowed from the Klingon school (e.g., gorxit sthanga to mean “worthless criminal”).

Beyond names and languages, the prose itself can evoke certain feelings around a setting or situation. The ideas of euphony and cacophony are most often associated with music (to describe, for instance, a virtuoso violin performance versus someone banging randomly on a piano). But they apply to language too. They mean, respectively, the effect of sounds being perceived as pleasant, rhythmical, lyrical, or harmonious, versus the effect of sounds being perceived as harsh, unpleasant, chaotic, and often discordant. One doesn’t need a song to hold any of those characteristics.

It’s not only words themselves that have euphony and cacophony, but the sentences and paragraphs into which they’re arranged. New writers are often advised by teachers, critique partners, or editors to vary their sentence structures and lengths to make their writing “sing” more or “flow” better. The same kind of sentence over and over, after all, gets rather dull. Yet it can also be very effective at creating cacophony when needed, used to reinforce the monotony of a dystopian city or the harsh nature of a lawless outpost.

When worldbuilding in sci-fi/fantasy, mood and vibes matter as much as the nitty-gritty of which ruler controlled what territory, or what kind of food this fictional civilization consumes. They pull the reader into the protagonist’s perspective of whether a place is safe or dangerous, whether a fictional people are considered peaceful or aggressive. Using the musicality inherent in words and sentences, the way a composer uses notes and melodies, helps set the right tone.

Music as Worldbuilding in Sci-Fi/Fantasy

But what about music itself? What role does that play in these fictional worlds?

The answer can say a lot about the world being built. In Star Wars, the very, very unfortunately named jizz music is used to create a sense of casual lawlessness. A swinging band in a seedy cantina or a mobster’s palace lets the audience know that this may be a place of disrepute, but its inhabitants don’t take themselves too seriously. Han Solo can flat-out shoot a guy (first) and no one cares.

The answer can say a lot about the world being built. In Star Wars, the very, very unfortunately named jizz music is used to create a sense of casual lawlessness. A swinging band in a seedy cantina or a mobster’s palace lets the audience know that this may be a place of disrepute, but its inhabitants don’t take themselves too seriously. Han Solo can flat-out shoot a guy (first) and no one cares.

Star Trek uses music to reinforce the characteristics of its alien races. Klingons are depicted as very serious about their culture, customs, and histories, and very reverent of warriors of the past. Of course they have their own form of opera, the grandest of Western music traditions.

And then there’s Tolkien’s Middle Earth, where characters frequently sing to tell a story or express a sentiment. The songs help build out the sense of realness in this made-up world, a feeling that these cultures have deep histories and traditions that expand beyond the pages of the book. The way they appear is telling as well; here are cultures in which singing is commonplace.

How fictional cultures in sci-fi/fantasy interact with music, and what kind of music exists, is fundamental to the world being created. Music can be used for religious ceremonies, for life events like weddings and funerals, or for communication, like a war drum or bugle. It can also be treated casually, just popular entertainment, or a tune someone hums as they go about their business.

Or, it can be omitted altogether.

For Starswept, I started with a simple question: what if a people who’d never heard music before suddenly encountered it? And from there came the question: wait, why would they never have heard it before?

For Starswept, I started with a simple question: what if a people who’d never heard music before suddenly encountered it? And from there came the question: wait, why would they never have heard it before?

Which led me to wonder, what is music for? Why did humanity develop it in the first place? And the answer I came up with was that old Hans Christian Andersen quote: “Where words fail, music speaks.” So I had to create a sci-fi world where words wouldn’t fail. The reason: telepathy. An ability to project thoughts and emotions directly onto others, negating the need to find creative ways to express oneself.

So what would happen when these people finally encountered music? The answers could have taken me any of several directions, but I chose: they’d become obsessed with it. I probably landed on that answer because I myself can’t imagine a world without music (I was handed my first violin when I was three and have been involved with some musical venture or another ever since). If these aliens had no music but became obsessed with that of Earth, what would they do to bring the sublime to their own world?

And so, music became the basis of my entire worldbuilding project for the Starswept trilogy. Also the basis of the entire plot, which is about a penniless viola student striving for what she thinks will be a better life on this music-obsessed alien planet, only to learn that her world isn’t what she thought, and she can’t leave things the way they are.

Most sci-fi/fantasy stories won’t have music so intimately intertwined in their worlds and characters. But still, it’s unavoidable. Many will treat music similarly to our own world. Aliens will sing lullabies. Fantasy creatures will play in bands. And that will make them seem a bit human behind the gobbledygook names and outlandish descriptions.

Music can also be used as a plot device. A lullaby unlocks the mystery of Star Trek: Discovery’s third season. An alien opera singer carries an important secret in The Fifth Element. Songs can jog character memories and introduce flashbacks, convey secret codes or express a character’s true feelings.

Invoking Sound Through a Silent Medium

Whether or not music is important to a story’s world, at some point, it will probably show up on a page. A still, silent page. While a lot of the examples I gave are from film and television—mostly out of expedience, since more people will be familiar with those—music is just as powerful on paper.

The most straightforward way to tell a reader how music sounds is to simply describe it in musical terms. To write about ascending scales or descending arpeggios, long trills or short drum beats, harmonious thirds or dissonant seconds. Flowing melodies or jagged ones, fast beats or slow.

Sometimes, a writer will draw upon familiar music from a shared culture, relying on the reader to know what they’re talking about. A twangy country song about a man, his truck, and his lost female lover. A prissy string quartet that feels like it should be played by people in powdered wigs. A soft yet sonorous chant that reverberates off stone walls.

Other times, more abstract means are called for—metaphors about tumbling notes or tying the song to a character’s emotions. A melody might be a river, babbling along a winding path. A character might hear their own joy in a song’s euphoric tone.

However one chooses to engage with it or not, music is inexorably intertwined with our world. And so, it becomes part of the fictional worlds we create as well. However far, far away the realm, however distant the galaxy, music will be part of it or, through its absence, say something nonetheless.